Remembering Charles Owen, a Beloved Early Campus Figure

Last year, while helping to assemble images for a photographic history of the Roanoke and New River valleys, I ran across a wonderful photo of Charles Owen, known to the students of Virginia Agricultural & Mechanical College (today Virginia Tech) as “Uncle Sporty.” Sometimes a photo really captures your interest and makes you want to learn more about the person shown.

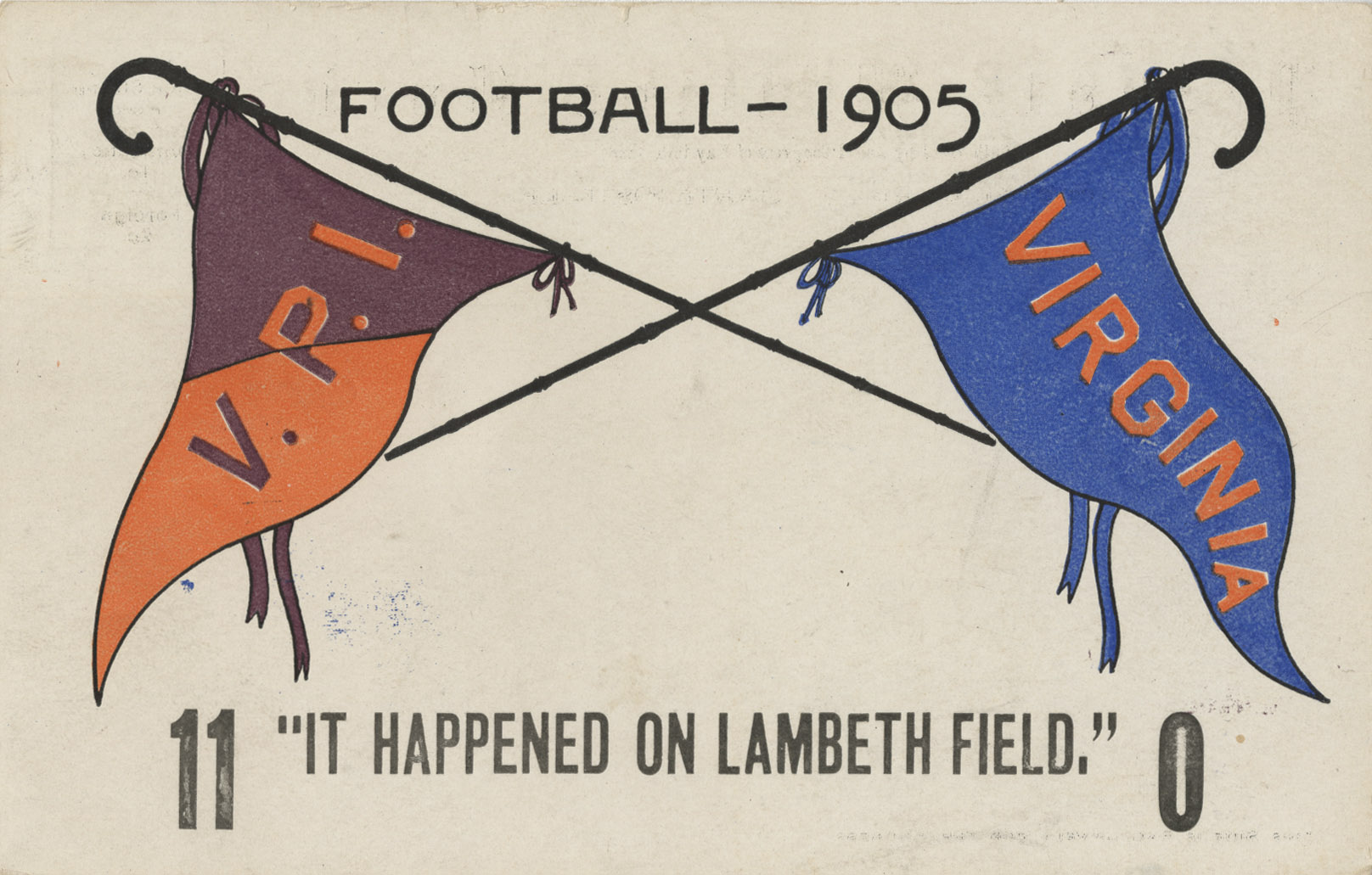

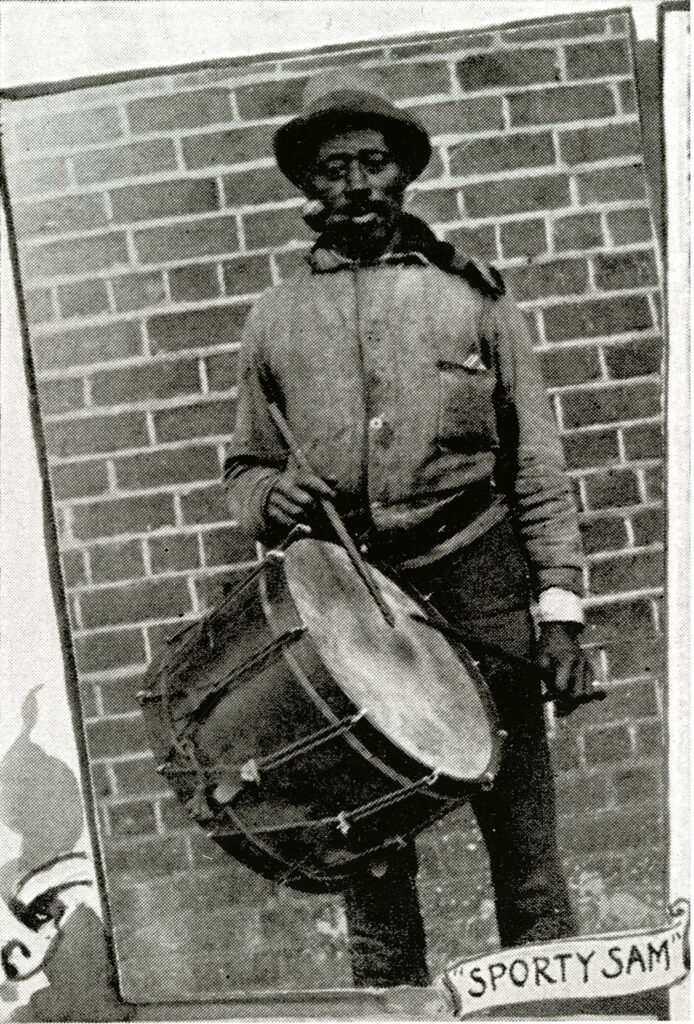

Charles Owen’s longstanding presence at the university began in 1890, when he was hired as a janitor for Barracks Number One (today Lane Hall). (Note that while some sources, including his own daughter’s death record, provide his surname as “Owens,” campus sources invariably identify it as “Owen,” so that is what I’ll use here.) Soon afterward, Owen assumed an additional duty that he’d perform for many years to come: according to Col. Harry Temple’s The Bugle’s Echo, an exhaustive history of the university’s early decades, Owen “took charge of a large snare drum which he attached to a leather belt about his waist. Ten minutes before Reveille each morning he would parade the area in front of the barracks, beating his drum. Sporty could actually beat out tunes on that drum; where he learned the art no one knew.” For nearly 20 years, Owen’s was one of the most familiar faces on campus and likely one of the first to be recognized by new cadets. Reminiscing on his years as a VAMC cadet, Henry Harris Hill (BS, 1907) recalled his first morning at college:

Very early in the morning I was awakened by a far off rumbling sound. For the life of me I couldn’t imagine what the noise was. It gradually came closer, so I got up and went to the window to look. Out on the parade ground was an old colored man beating a drum that looked like it was about five feet deep. The colored man was Uncle Sporty who was waking the boys preliminary to Reveille.

Unfortunately, despite some rather in-depth searching, I could learn little about Owen. The 1900 census recorded a Charles Owens living in Blacksburg with wife Ellen. The Owens’s sizable household included three daughters, Bell, Lucy, and Nellie; the daughters’ husbands, Lev, Hiram, and Reuben (all with the surname Collins); four Collins grandchildren; Charles and Ellen’s adopted son John Hickman; and niece Ella Collins. The census describes Charles Owen as a janitor but fails to record his and Ellen’s ages.

(To throw some confusion on the matter, the census lists a second Charles Owens living in Blacksburg and also working as a janitor in 1900. Later census records indicate that this Charles Owens also worked on campus, but following this man’s documentary trail we learn that he is not the man who came to be known as Uncle Sporty.)

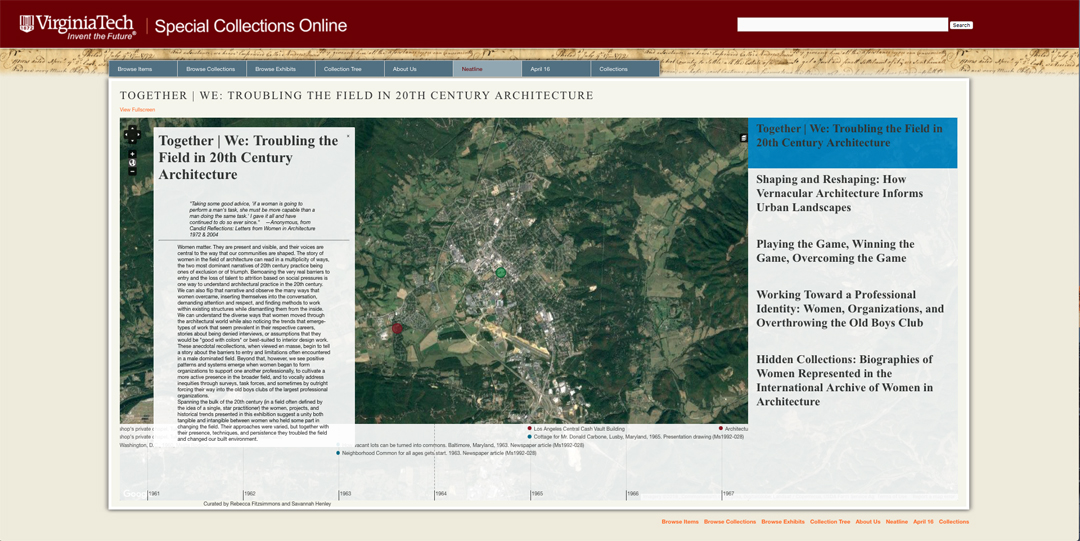

Owen’s photo first appears in The Bugle (the college annual) in 1899. He is shown in a composite photo of other maintenance staff and is identified only as “Sporty Sam.” Given the time period and the fact that another African-American campus employee is referred to as “Smoky Sam,” we can infer that the name “Sam” was almost certainly being used here as a diminutive of “sambo,” a derogatory term that, even if used in jest, showed a flagrant disrespect.

Owen’s photo would again appear in the 1908 Bugle. By that time, he’d picked up the nickname “Uncle Sporty,” and while the term “uncle” when applied to African-American men of that era was also unquestionably derogatory, its use by the cadets in referring to Owen would seem to indicate an improvement of sorts in his status and the affection that they held for him. (We might also bear in mind that the cadets invariably referred to William Gitt, a white man who succeeded Owen as a worker in Lane Hall (and about whom I posted three years ago), as “Uncle Bill.”)

Illustrating the standing that Owen held in the cadets’ minds, his photo appears near the front of the annual, preceded only by the volume’s dedication page.

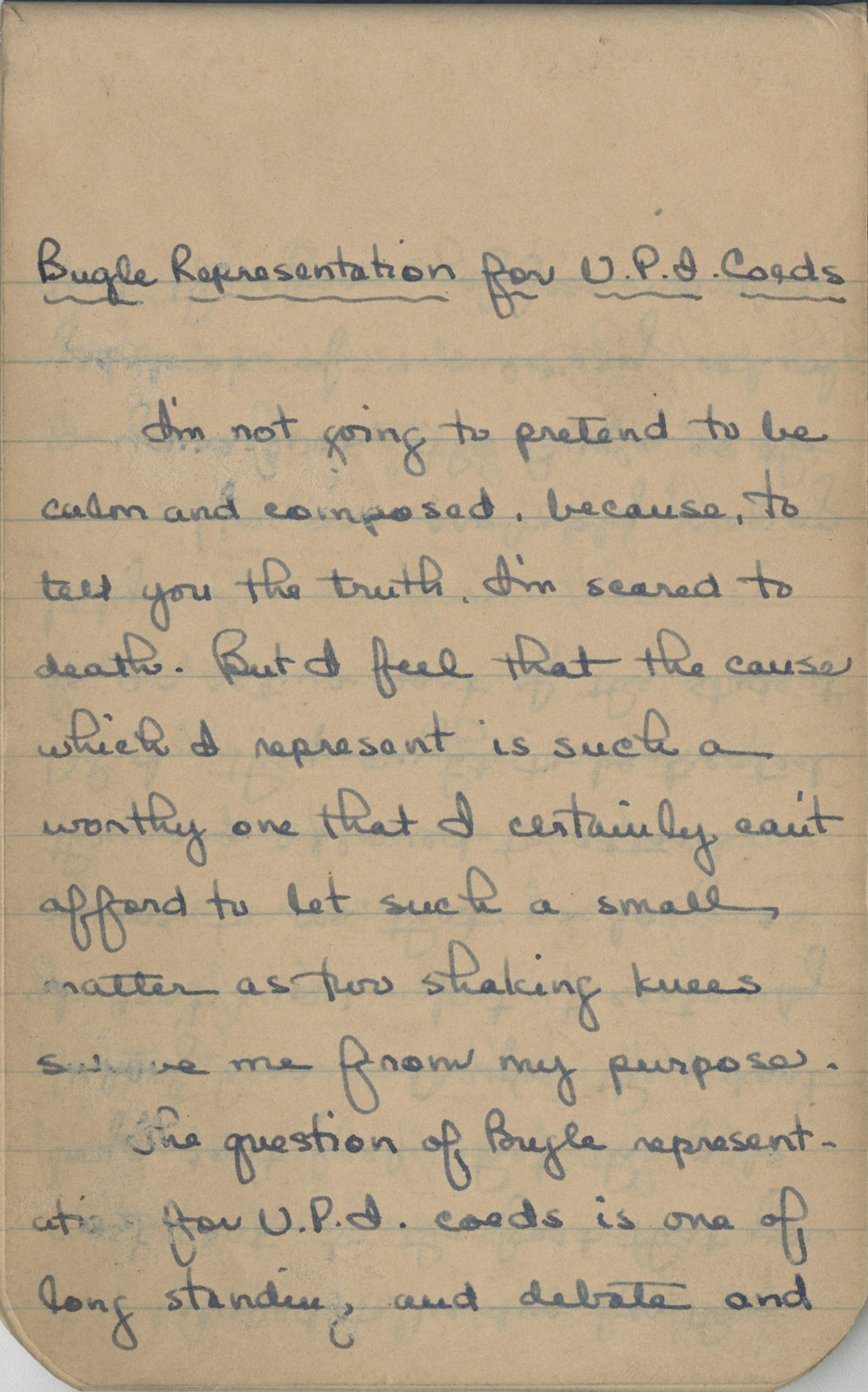

Below Owen’s photo is a poem, attributed to “J.D.P., ’08” (John Dalrymple Powell of Portsmouth, Virginia), written in the “Negro dialect” commonly used by white writers of the day. While the delivery is demeaning, the sentiments seem heartfelt:

Bein’ as I’se de fust to see yo’ when yo’ come,

And as I says Good-bye to every one,

And since I takes most painful care

Of all my boys throughout the year,

It seems to me most sartin’ sure

Dat I should be right here befor’

De folks of all dese friends of mine

And gib’ a greetin’ which dey’ll find,

Dat dough dey lib’ to be past forty,

Will make dem tink of “Uncle Sporty.”

According to The Bugle’s Echo, Owen continued to perform his campus duties until mid-1909, when, due probably to age and failing health, he retired and left Blacksburg. “He took with him,” writes Temple, “the great well-wishes and gratitude of the cadets.” The Virginia Tech (the forerunner of today’s Collegiate Times) of March 2, 1910 reported that Owen had suffered a stroke, leaving his entire left side paralyzed. Just three weeks later, the newspaper announced Owen’s death. In eulogizing him, the editor offered what he considered high praise, but even here the newspaper could not resist inserting a backhanded “compliment”:

Charles Owen, the old negro janitor who for years has been known by the familiar name of “Uncle Sporty,” and who was loved and respected by hundreds of students and alumni of V. P. I., died at his home last week after a lingering illness. Owen had for many years been janitor of Number One barracks and his sterling honesty and respectability as well as his never-to-be-forgotten duty of awakening the sleepers each morning with the rumbling of his ancient drum, had made him a familiar and unique figure here. He was of the old order, now seen no more among the negroes, and his death is sincerely mourned by everyone who knew him. He is survived by several children, two of whom occupy positions with the college.

The Bugle’s Echo notes that Owen’s standing at the university was such that students proposed providing the pallbearers and a firing party for his burial service, only to find that the funeral had been held before these arrangements could be made. Still, the cadets collected a “substantial sum of money,” according to Temple, “and a huge spray of flowers was ordered to be placed upon his grave.” Shortly thereafter, The Virginia Tech published a poem by M. W. Davidson (BS, 1901) entitled “Uncle Sporty’s Drum,” the third stanza of which reads:

No matter where roams Hokie’s man, his memory never failing;

He ponders on the long ago, though often rough the sailing.

The strife is long, the fight grows hot, and is ever lost by some,

But not by them who learned the way, where Sporty beat that drum.

A memorial also appeared in The Bugle for that year, featuring Owen’s photo and another poem.

Though the newspaper mentioned that two of Owen’s children continued to work at the university in 1910, nothing about them could be found. The 1910 census shows Ellen “Owns,” Charles’ 35-year-old widow, still living in Blacksburg, together with son-in-law “Rubin” Collins and two grandchildren. The census-taker noted that Rubin was working as a janitor in the “VPI Halls.” That same census shows another son-in-law, Hiram Collins, working as a janitor in the “YMCA Hall” (today the College of Arts and Human Sciences Building).

It isn’t easy, given the length of time that’s elapsed since his death and the little information at hand, for us to draw conclusions about Owen’s daily life, to put it in the context of the times, to know how he felt about his work at VPI and the students with whom he regularly interacted. (We haven’t even managed to conclusively identify his surname.) The little that we’ve learned of Charles Owen and his term of service here illustrates the larger, complicated topic of race relations of the era. It may be naïve and overreaching for us to say that Owen’s legacy was one of a slowly evolving, growing acceptance of and respect for African Americans in the campus community, but there can be no doubt that his work contributed to the university’s growth in its early decades, that his longstanding presence helped to instill in the students an affection for their school, and that he continued to be fondly remembered by university alumni for many decades following his death.

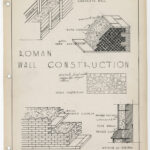

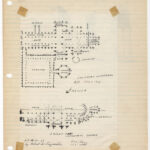

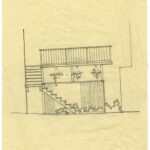

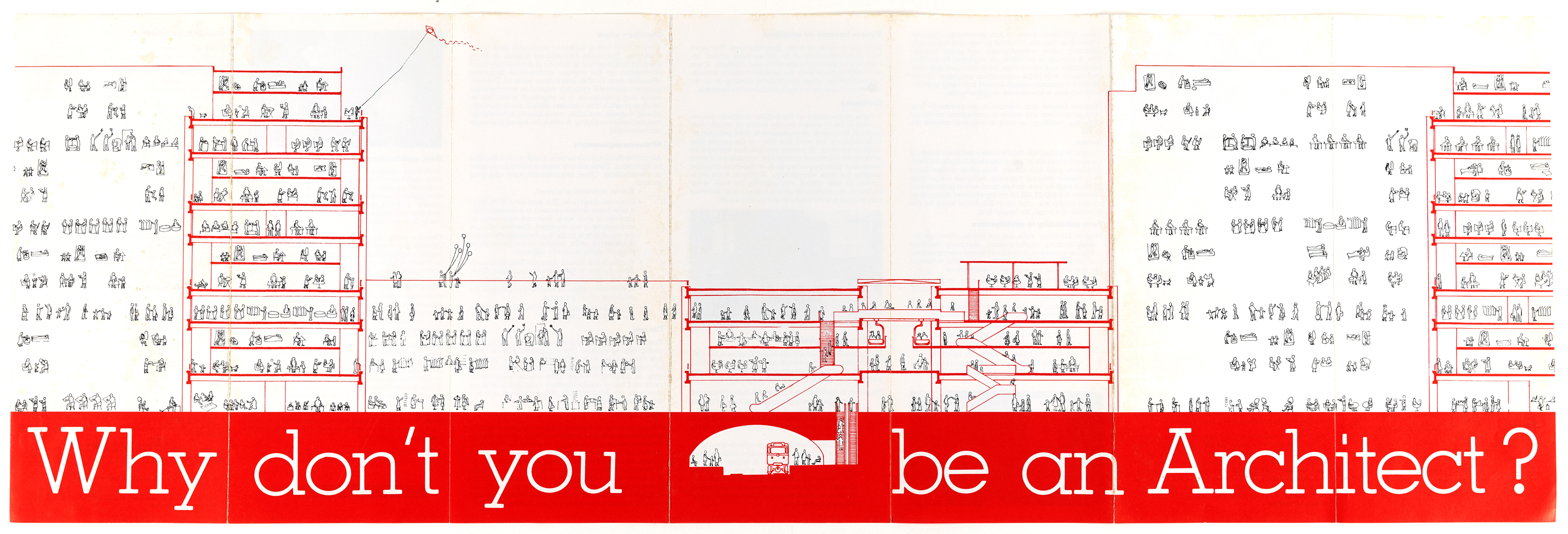

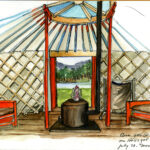

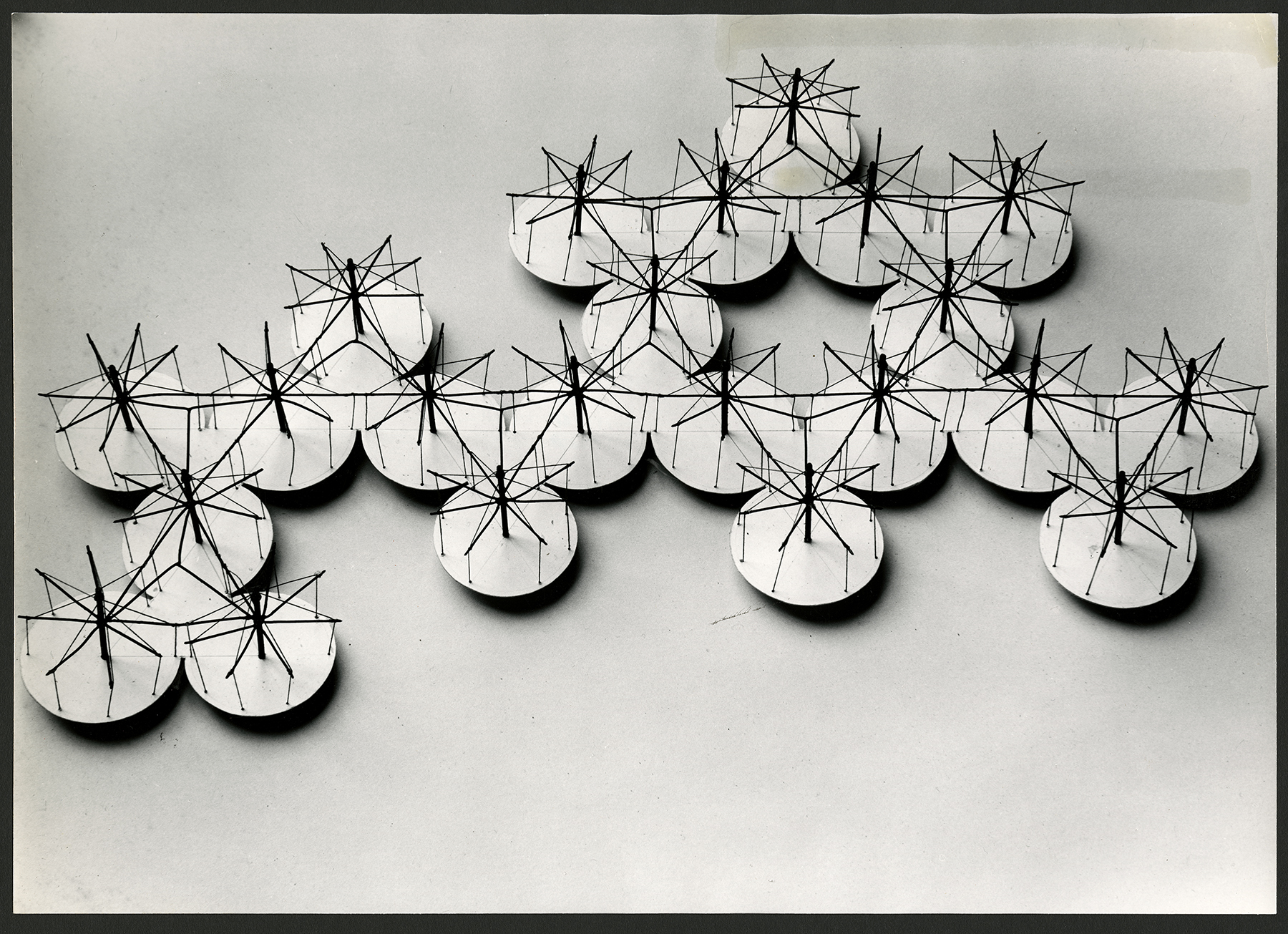

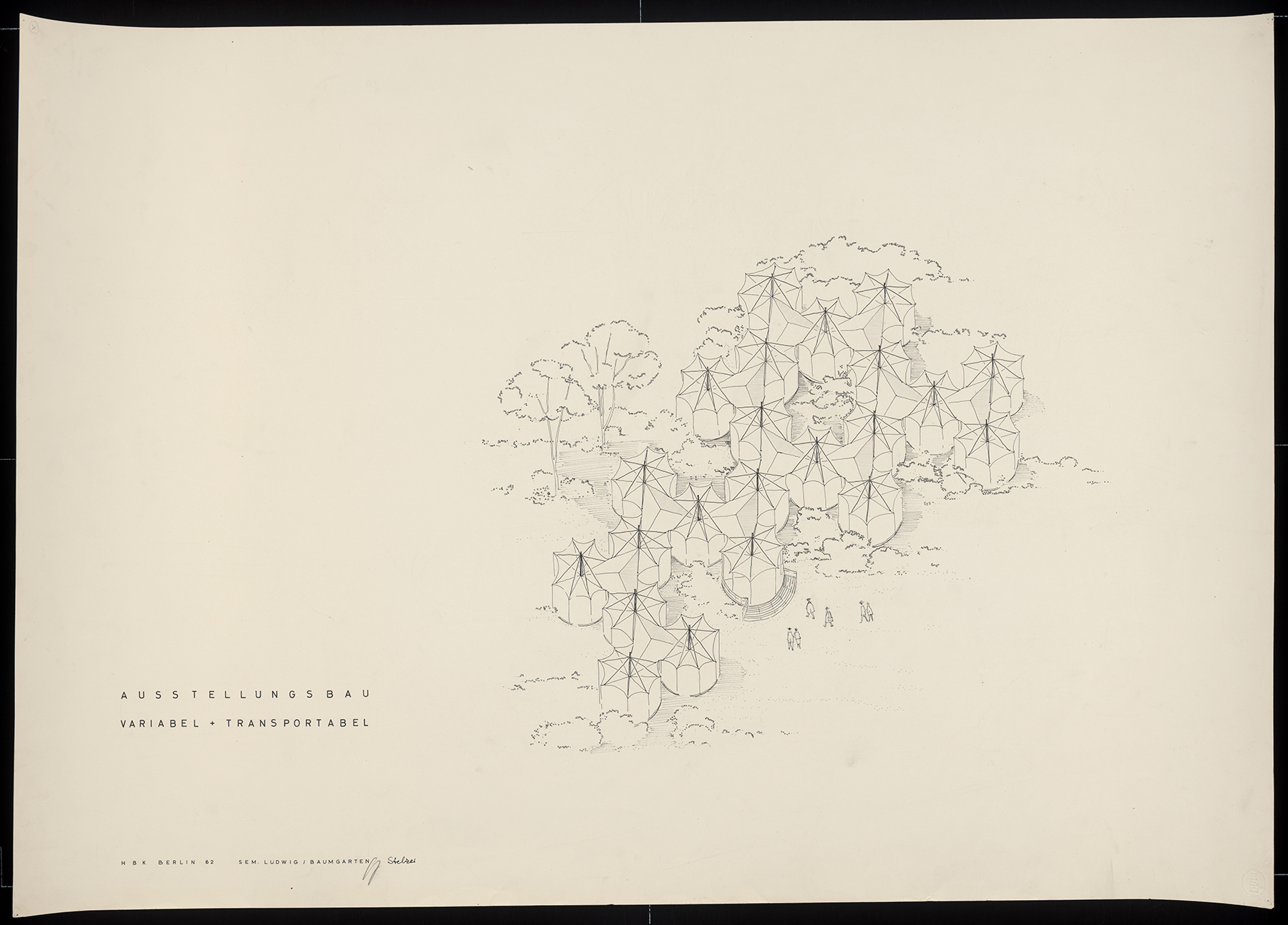

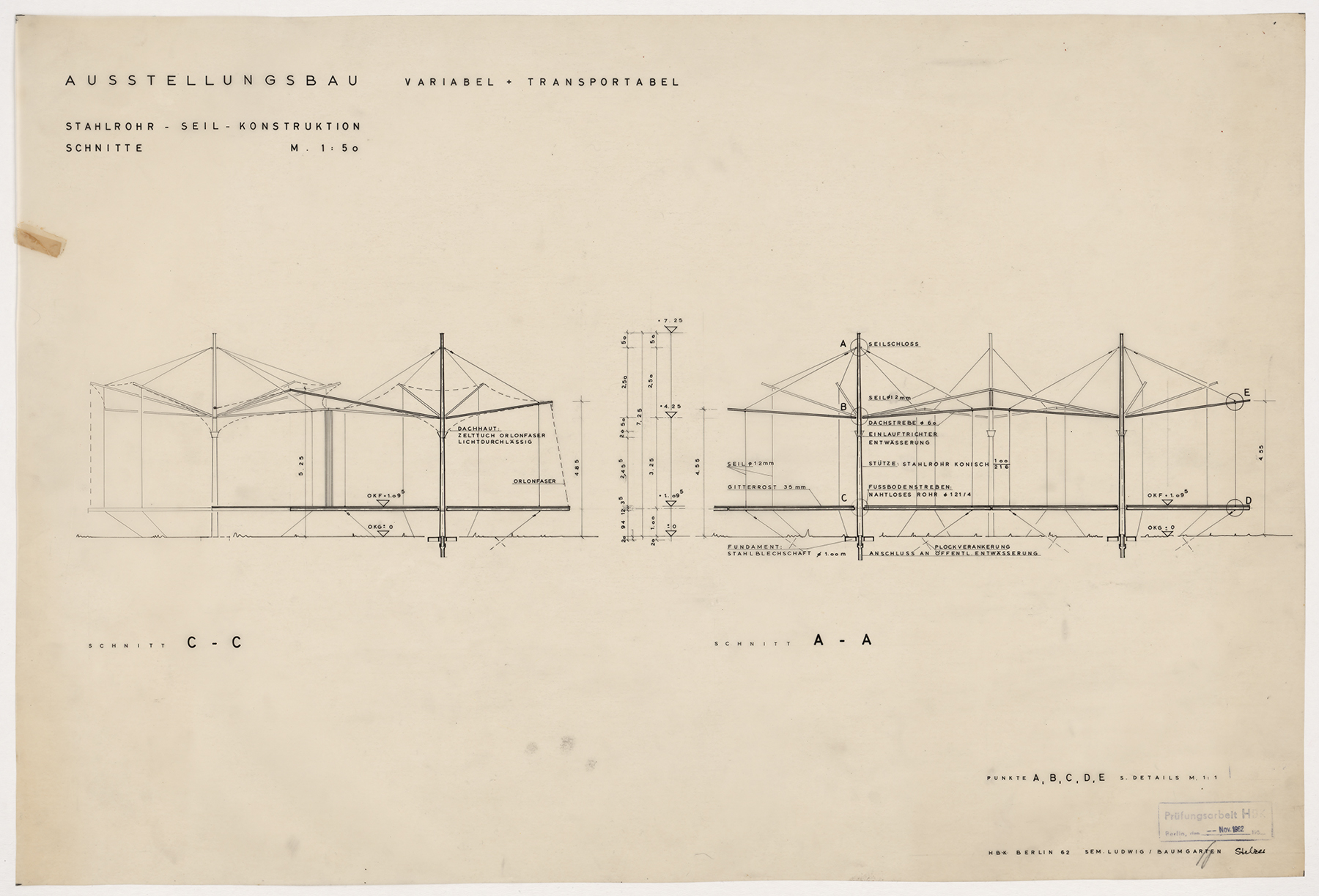

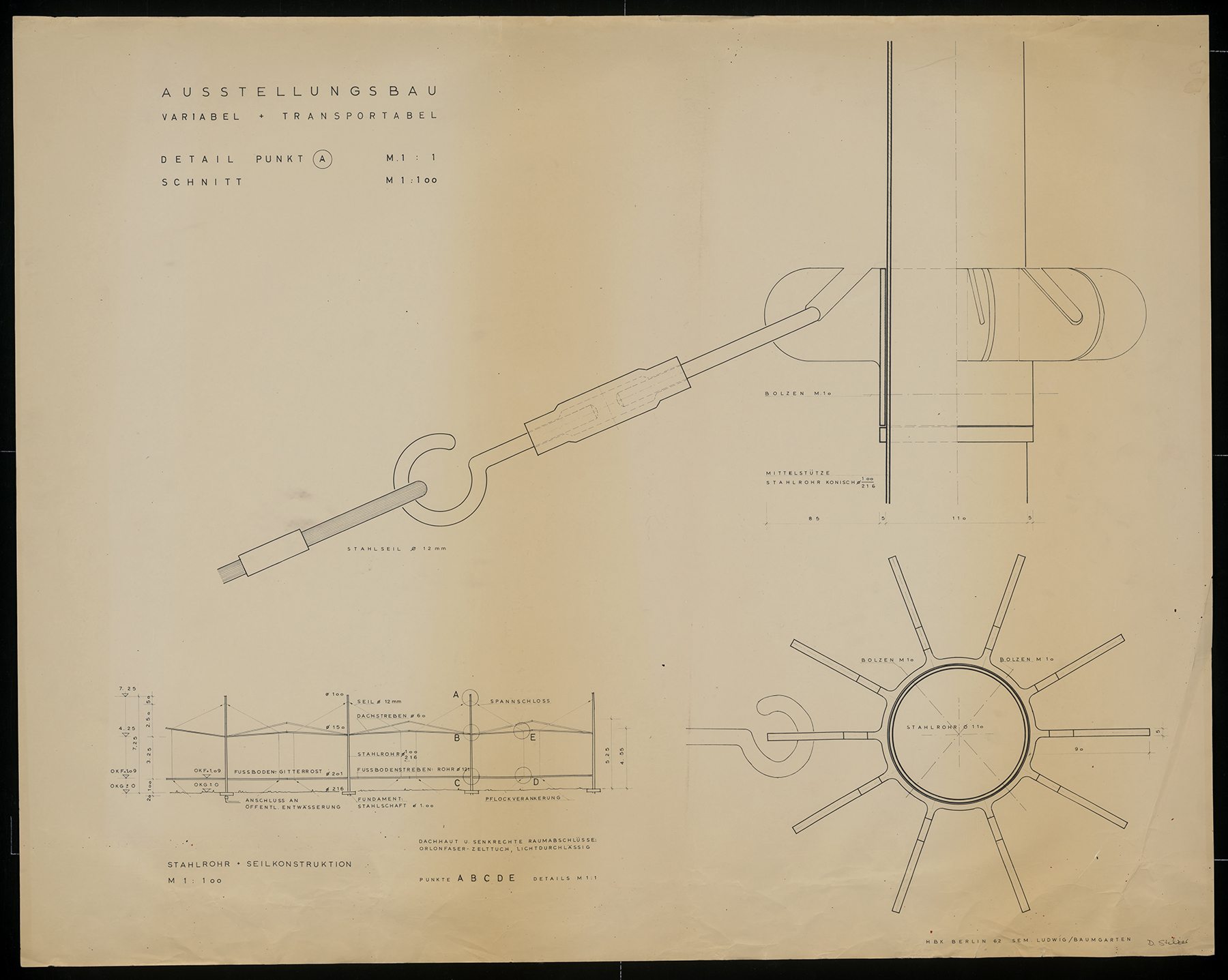

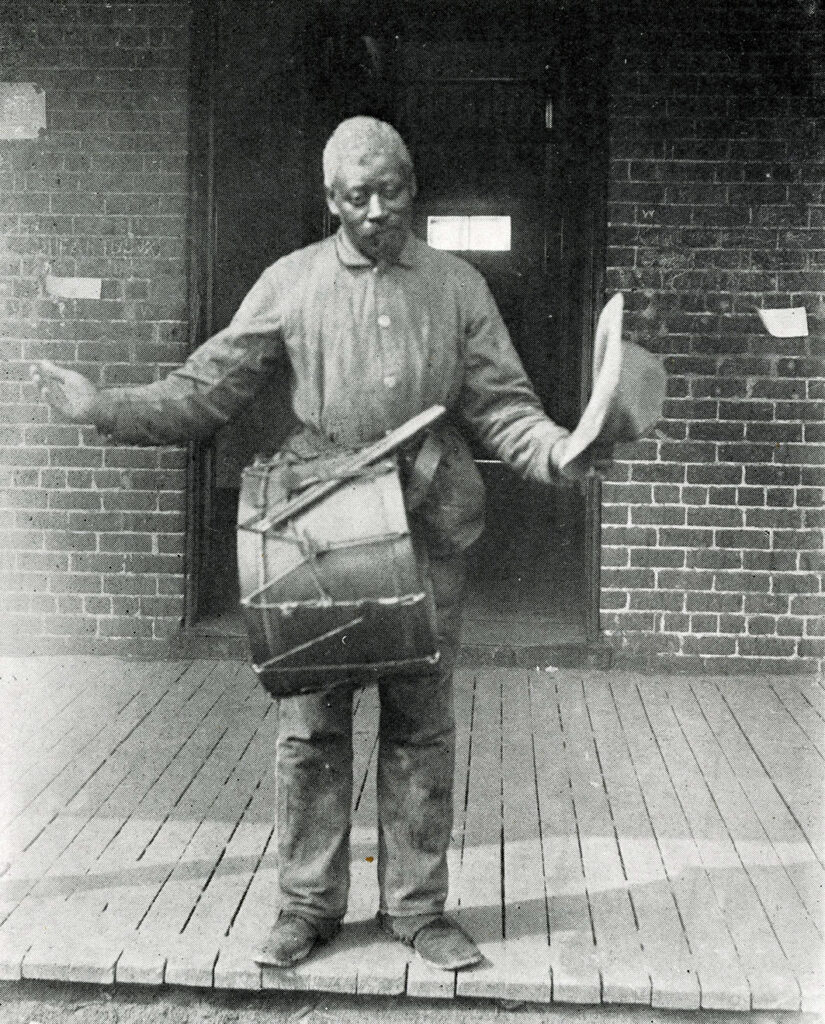

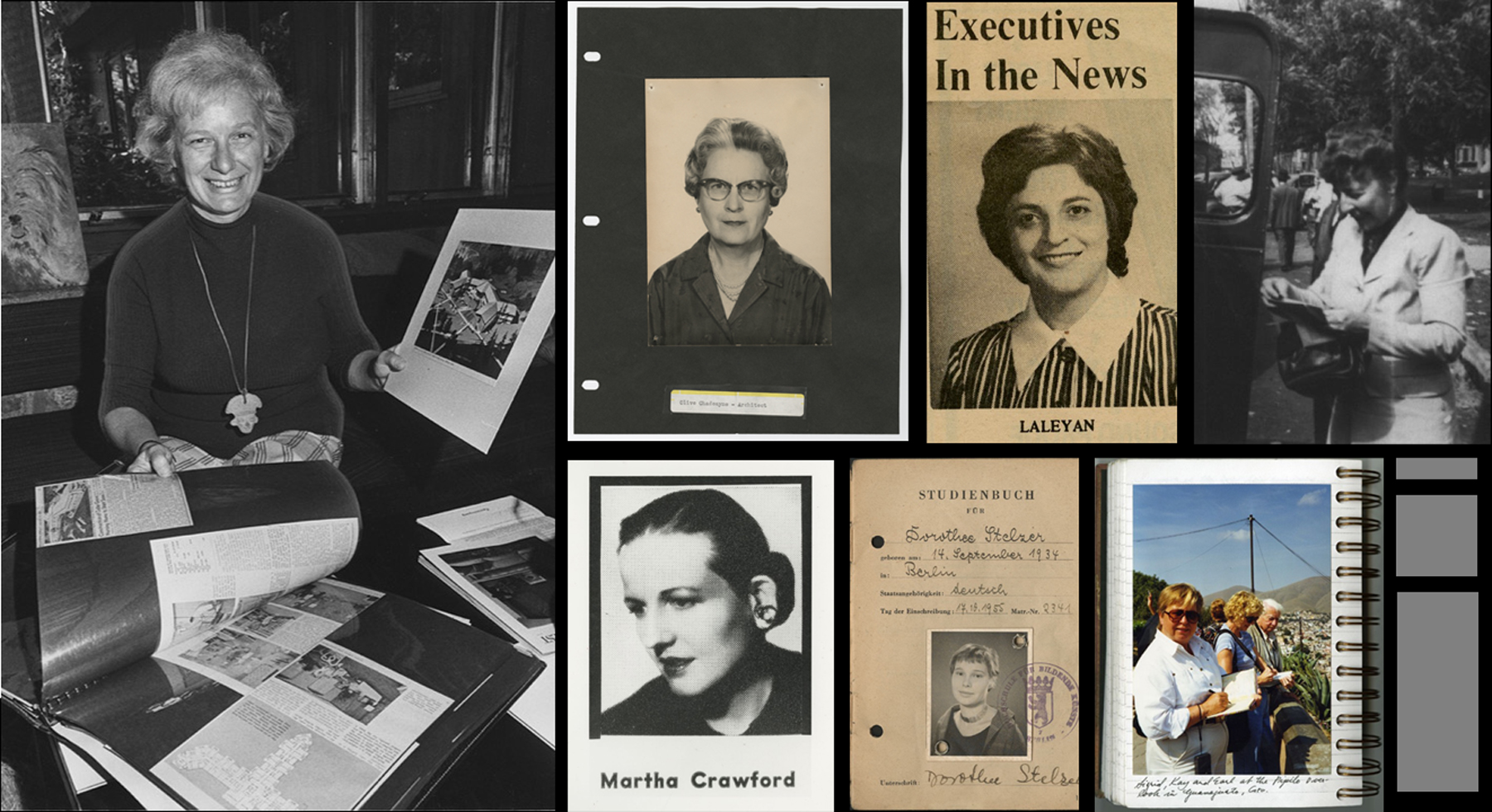

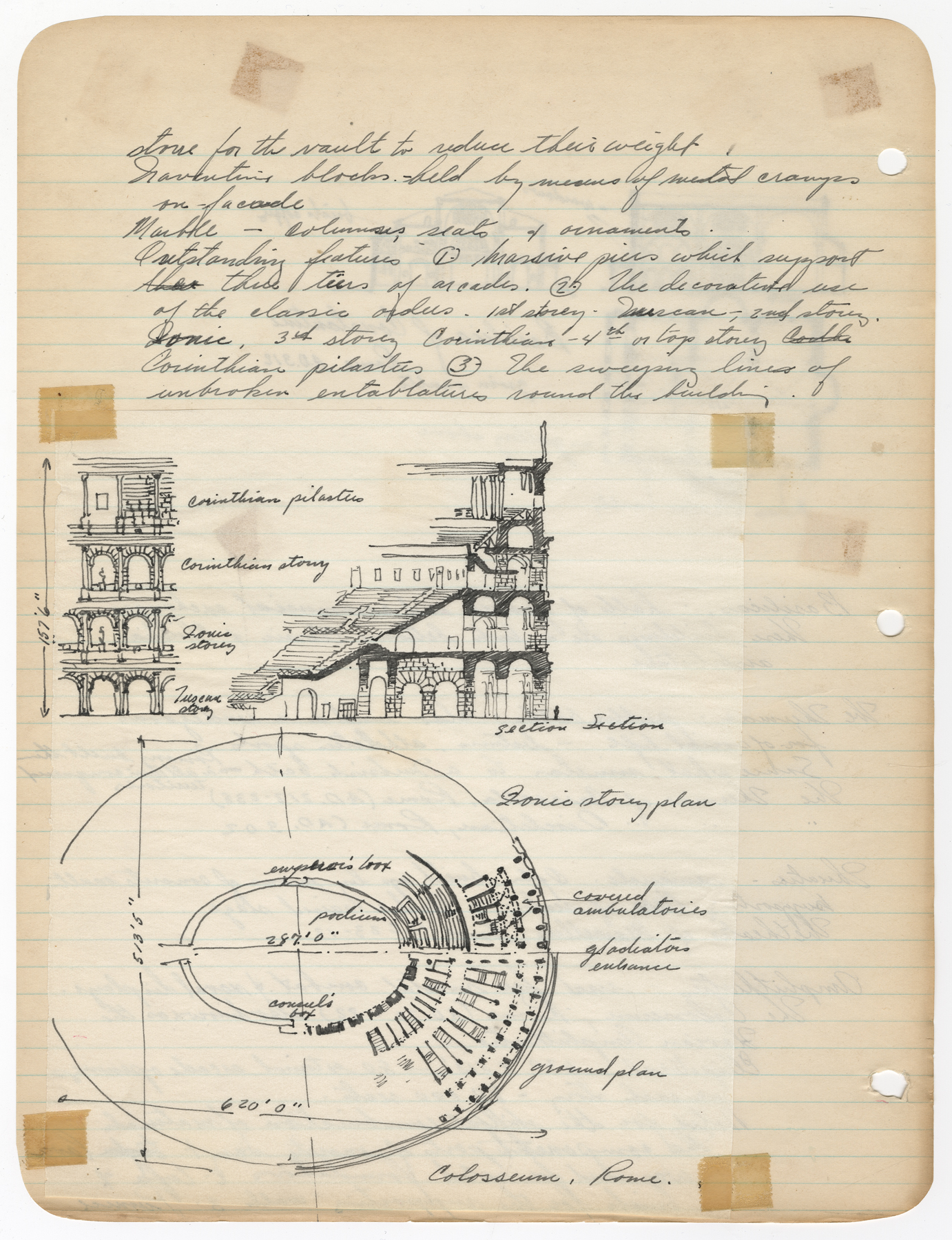

Architectural practice is full of moments of quick, insightful sketching. These bits of paper show the need to record an otherwise fleeting design idea or to communicate a thought when words are insufficient. Sketches made during student years show the process of working through architectural design and honing drawing techniques. These drawn remnants turn up in many architectural collections in the form of notes, scribbles, and concept sketches. They offer valuable insights into the career and studies of an architect and they also offer pure visual pleasure and inspiration to other creative individuals.

Architectural practice is full of moments of quick, insightful sketching. These bits of paper show the need to record an otherwise fleeting design idea or to communicate a thought when words are insufficient. Sketches made during student years show the process of working through architectural design and honing drawing techniques. These drawn remnants turn up in many architectural collections in the form of notes, scribbles, and concept sketches. They offer valuable insights into the career and studies of an architect and they also offer pure visual pleasure and inspiration to other creative individuals.