Cato Lee: Pioneer of the Lee-aphon Clan by Gigi Lee-aphon tells the fascinating stories of Cato Lee, one of the early Chinese students at Virginia Tech, and the members of his family. Written by Cato Lees daughter, Gigi, the ninth of his ten children, the book gives insights into the challenges faced by family members as they confronted Chinese, American, and Thai cultures. The author uses family stories to give the reader a better understanding of the life of Cato Lee. The book was published by Lotus Seed Press in 2017.

Cato Lee, who graduated in 1927 in Mechanical Engineering, was one of the first six Chinese students at Virginia Tech. The University Archives’ site, “First International Students at Virginia Tech,” lists the first and early international students by year and country: http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/diversity/InternationalVPI/

Born Lee Kee Tow in Bangkok, Thailand in 1904, Cato Lee was the son of Lee Tek Khoeia, a Chinese immigrant and merchant from Canton, and Noei Lamson, the youngest child of one of the most prominent families in Thailand. Because his father was a playboy, Cato was raised in unusual circumstances in Canton, China from the time he was four. When he was fourteen, his father enrolled him in an English/Chinese school in Hong Kong. He became a British subject while he was in Hong Kong, a status that his father already had. The British passport made it easier for him to travel to the United States.

When Cato was 17, his close friend from Hong Kong, Tien-Liang Jeu talked him into going to study in the United States. Tien-Liang already had visited the United States and enrolled at Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia. The two young men made the arduous journey by ship from Hong Kong to Vancouver and then traveled by train across the United States to New York City. Since he did not have much money, Cato waited on tables at a small restaurant before he enrolled in school. Because he was younger than Tien-Lang Jeu, who entered Virginia Tech (then called Virginia Polytechnic Institute or V.P.I.) in 1921, Cato first attended and graduated from Fork Union Military Academy a military high school for cadets in Fork Union, Virginia.

Tien-Liang, whose nickname at V.P.I. was Ting Ling, earned a degree in electrical engineering. According to his Bugle page, his highest ambition is to turn the wild and destructive forces of the mighty Yangtse and Yellow Rivers into power that will illuminate all China. (1924 Bugle, p. 61)

Cato Lee entered V.P.I. in 1923 and earned a degree in mechanical engineering in 1927. He played on the varsity track and tennis teams and belonged to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers and the Lee Literary Society. His Bugle page (1927, p. 183) includes a quote from Kipling:

But there is neither East nor West, border, nor breed, nor birth,

When two strong men stand face to face, tho they have come from the ends of the earth.

The commentary on his Bugle page indicates that Lee was not only a student but also taught his fellow cadets by “showing us that the gentleman of the East is not different from the gentleman of the West.”

Virginia Tech was very important to Cato Lee. Gigi Lee-aphon wrote in an email that she learned to say the word bugle at a very young age, not knowing it was an English word. Her fathers cadet uniform, sword, and sash were neatly hung on a stand in a corner of his bedroom for many years. I could admire it, she said, but better not touch it.

The image on the books cover shows Cato Lee and his bride, Kim Reiw, the daughter of a Chinese businessman. They only met because he stopped off in Thailand to visit his Thai mother on his way back to China. The couple married soon after they met and lived in Bangkok. Kim Reiw is wearing the wedding dress her parents ordered from Hong Kong. The book describes the couple’s glamorous wedding at one of the royal palaces in Bangkok where they both wore traditional Thai garments. They were known as the Romeo and Juliet of Thailand.

Like all archives, Special Collections at Virginia Tech holds a rich store of fascinating stories. One of these is the

Like all archives, Special Collections at Virginia Tech holds a rich store of fascinating stories. One of these is the

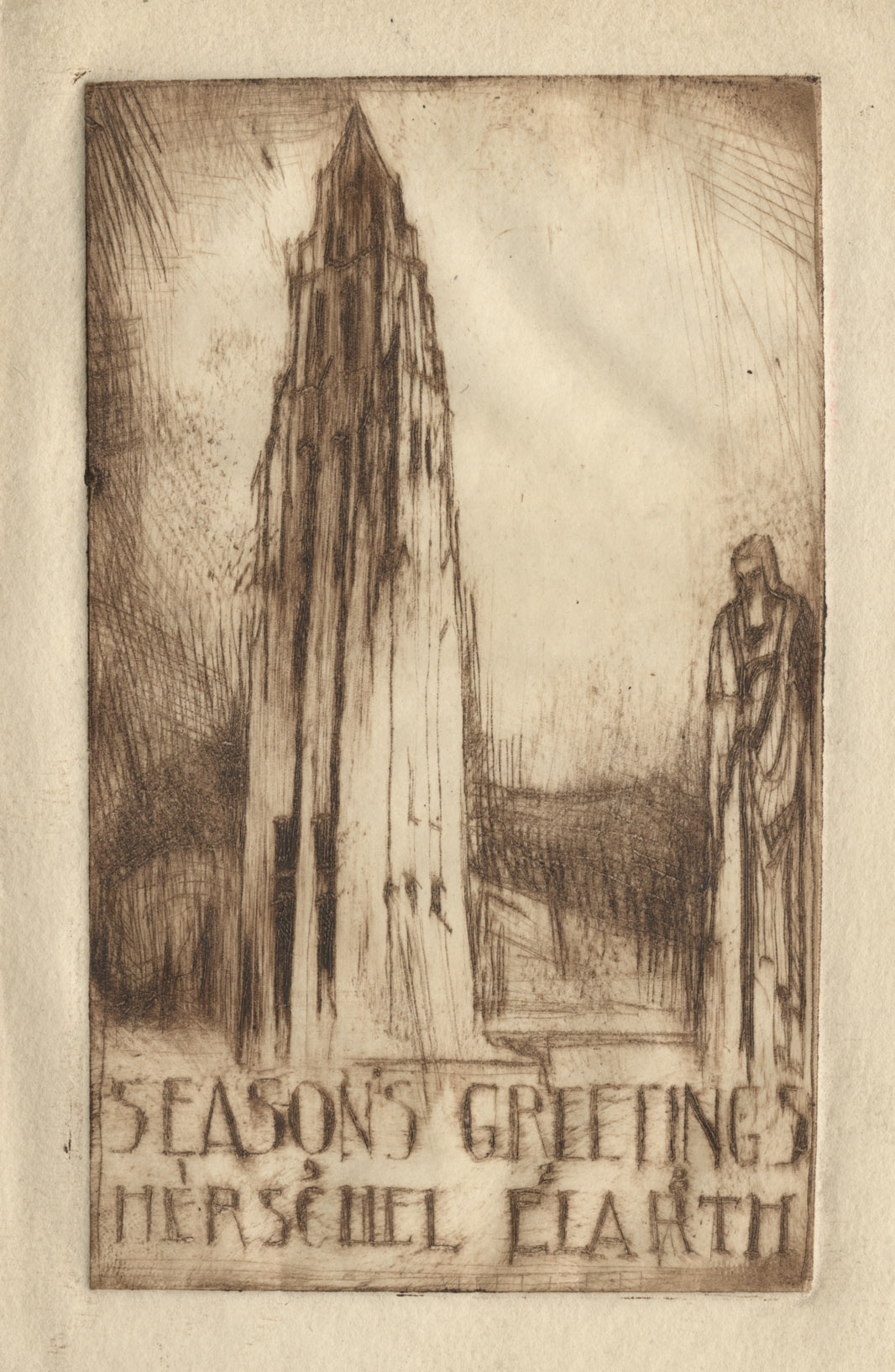

The Professors Elarth

The Professors Elarth

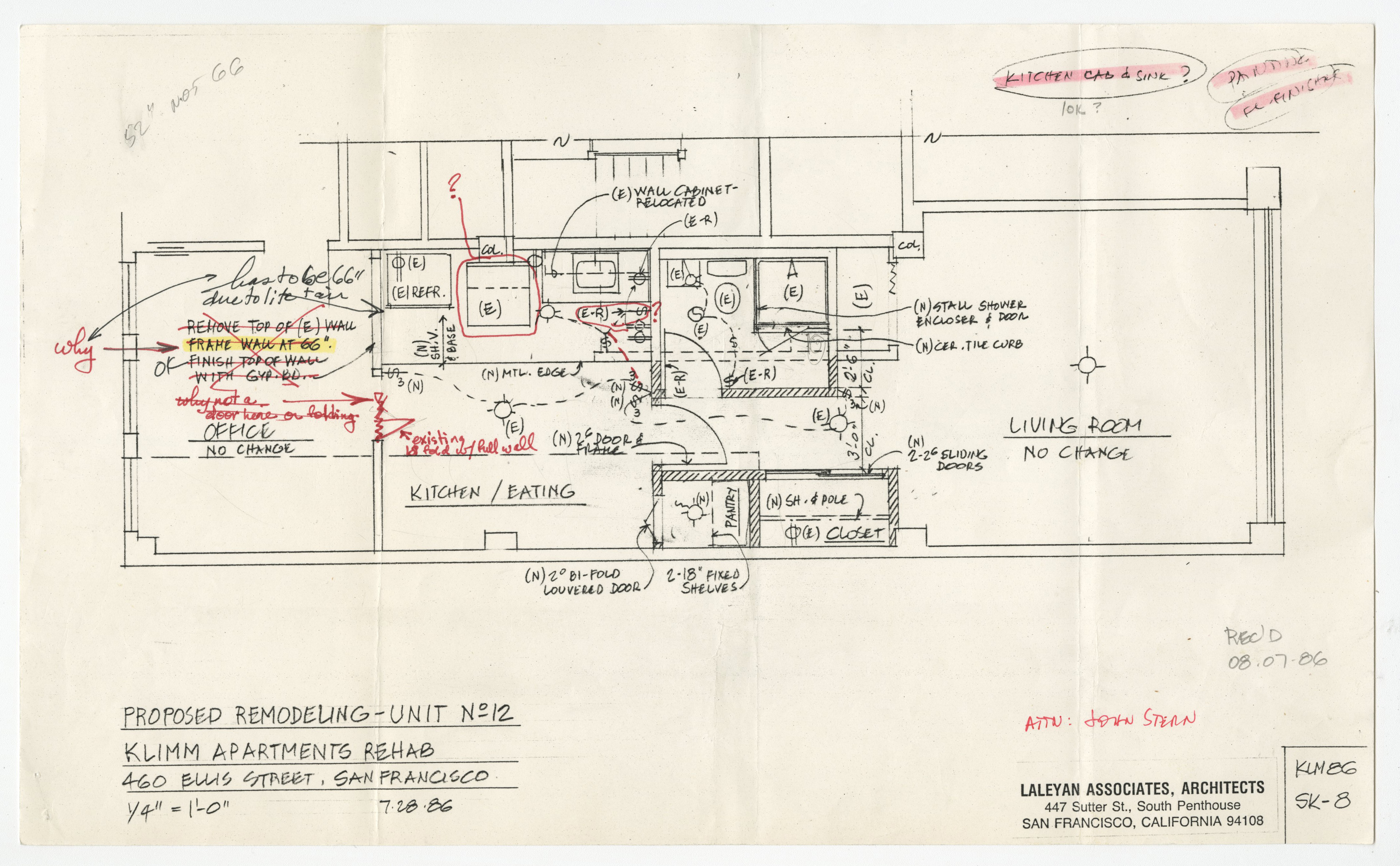

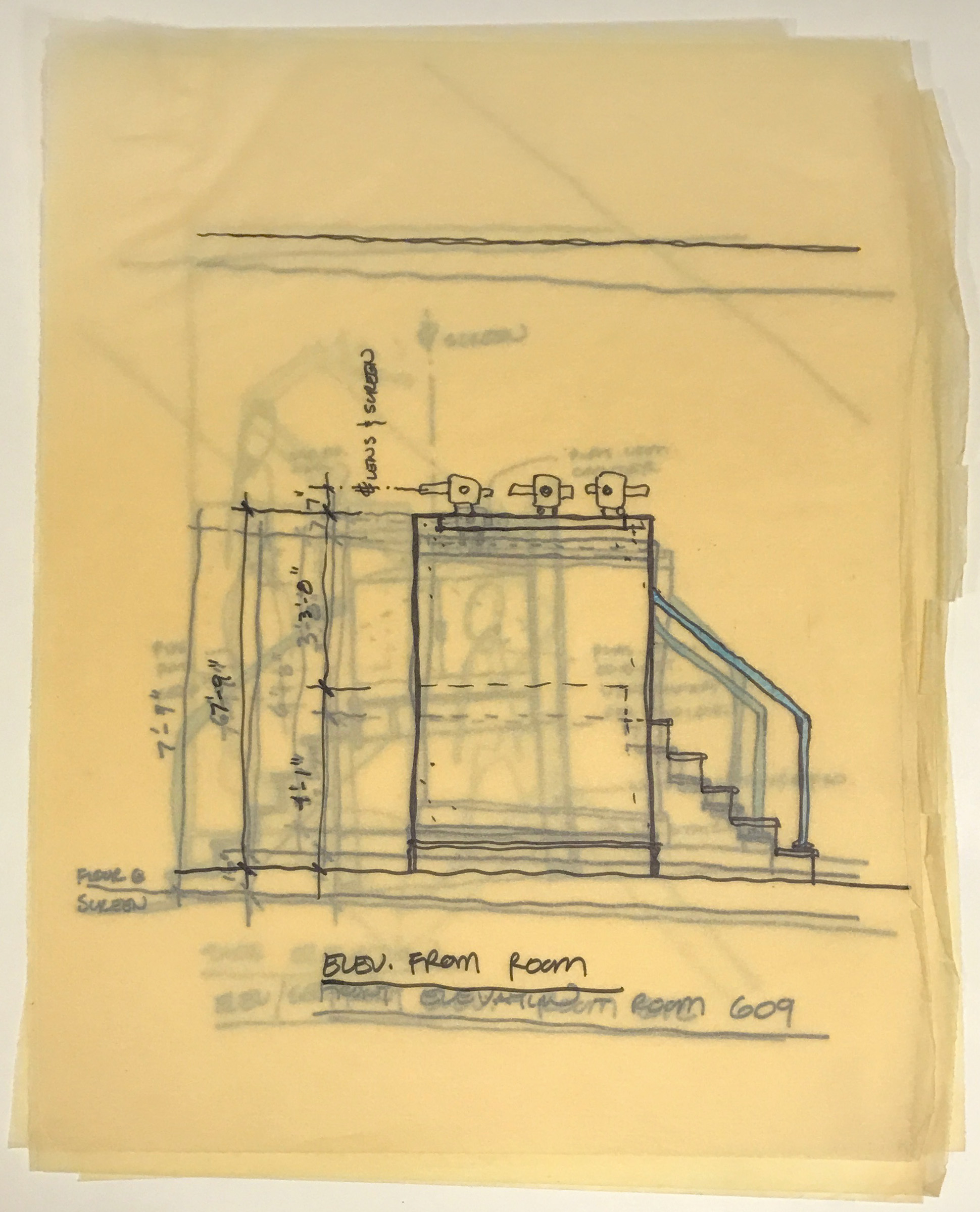

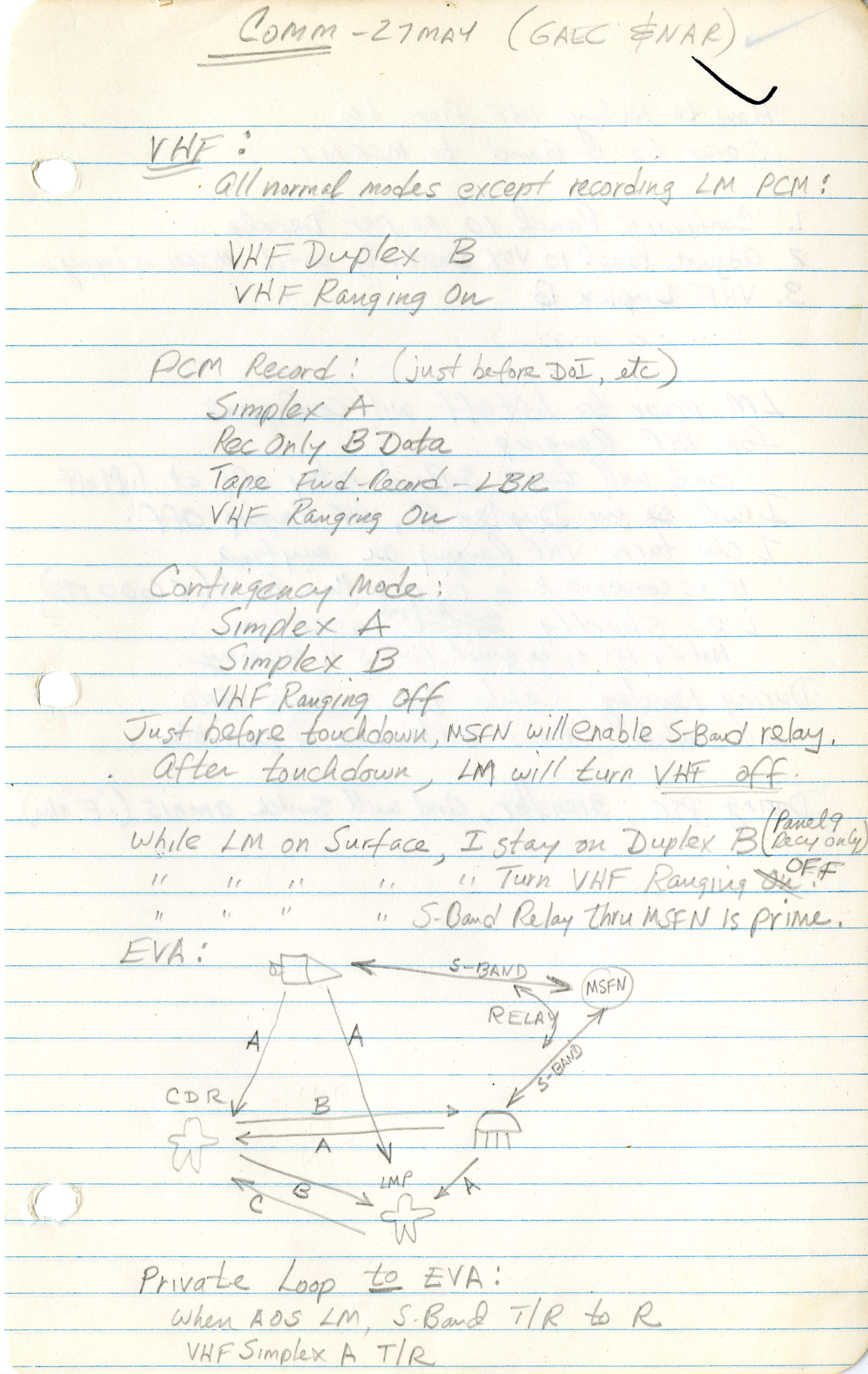

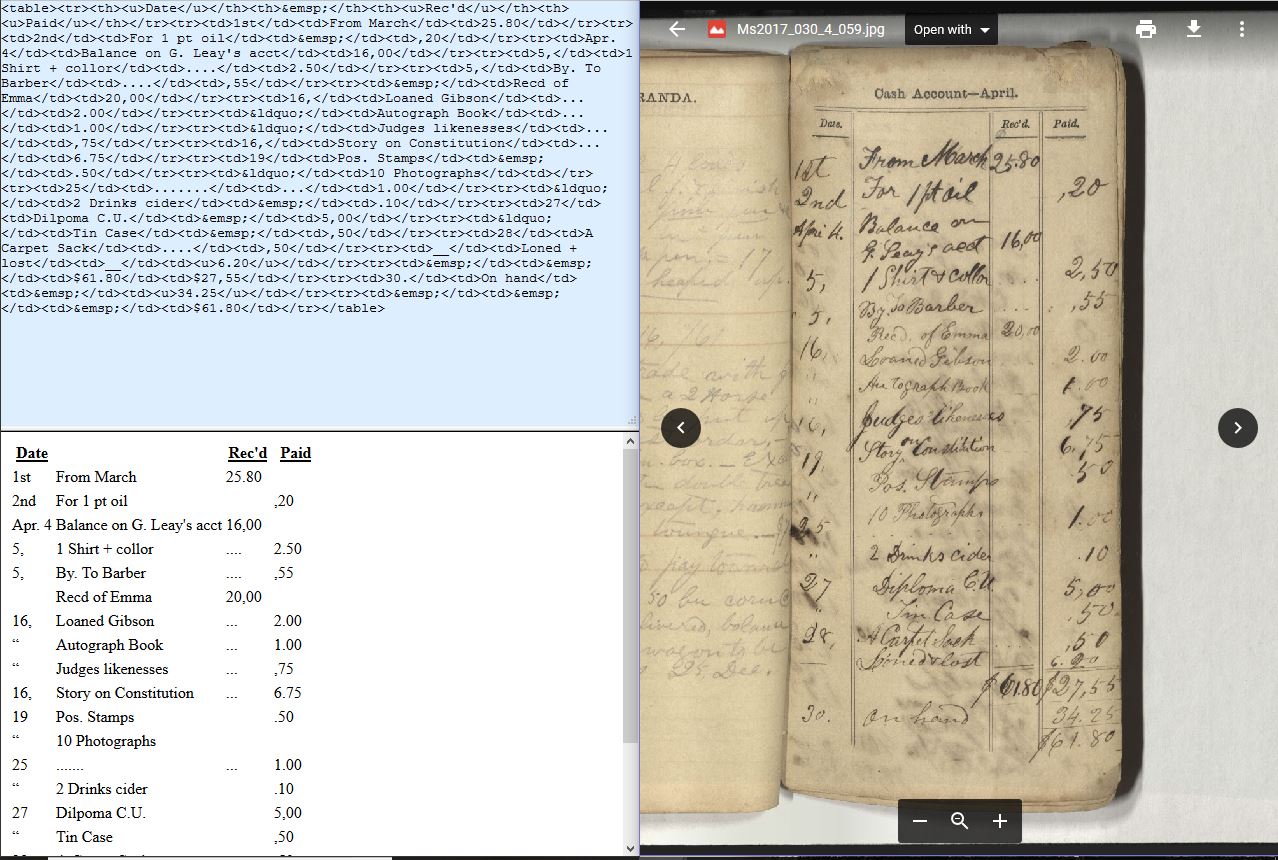

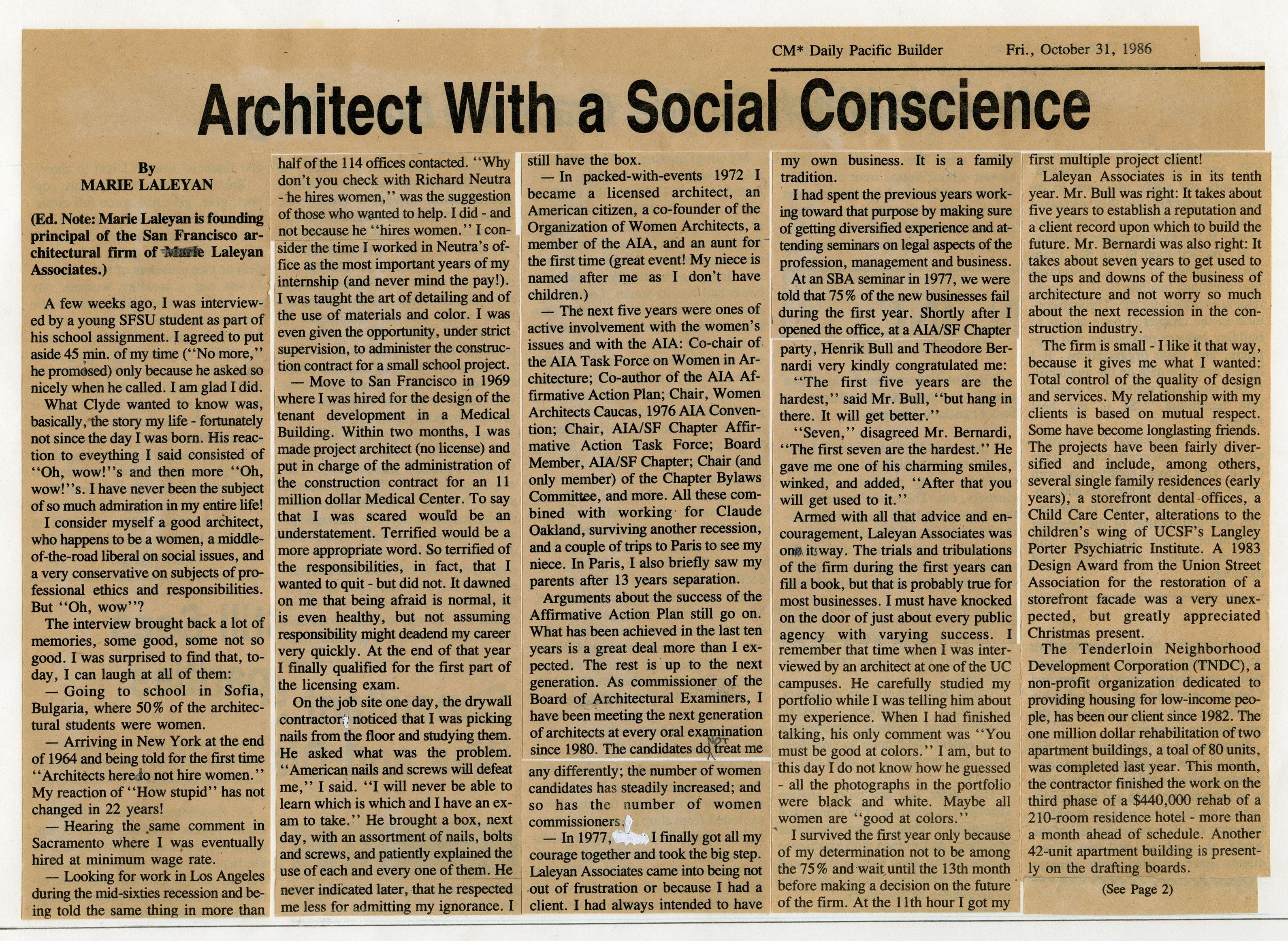

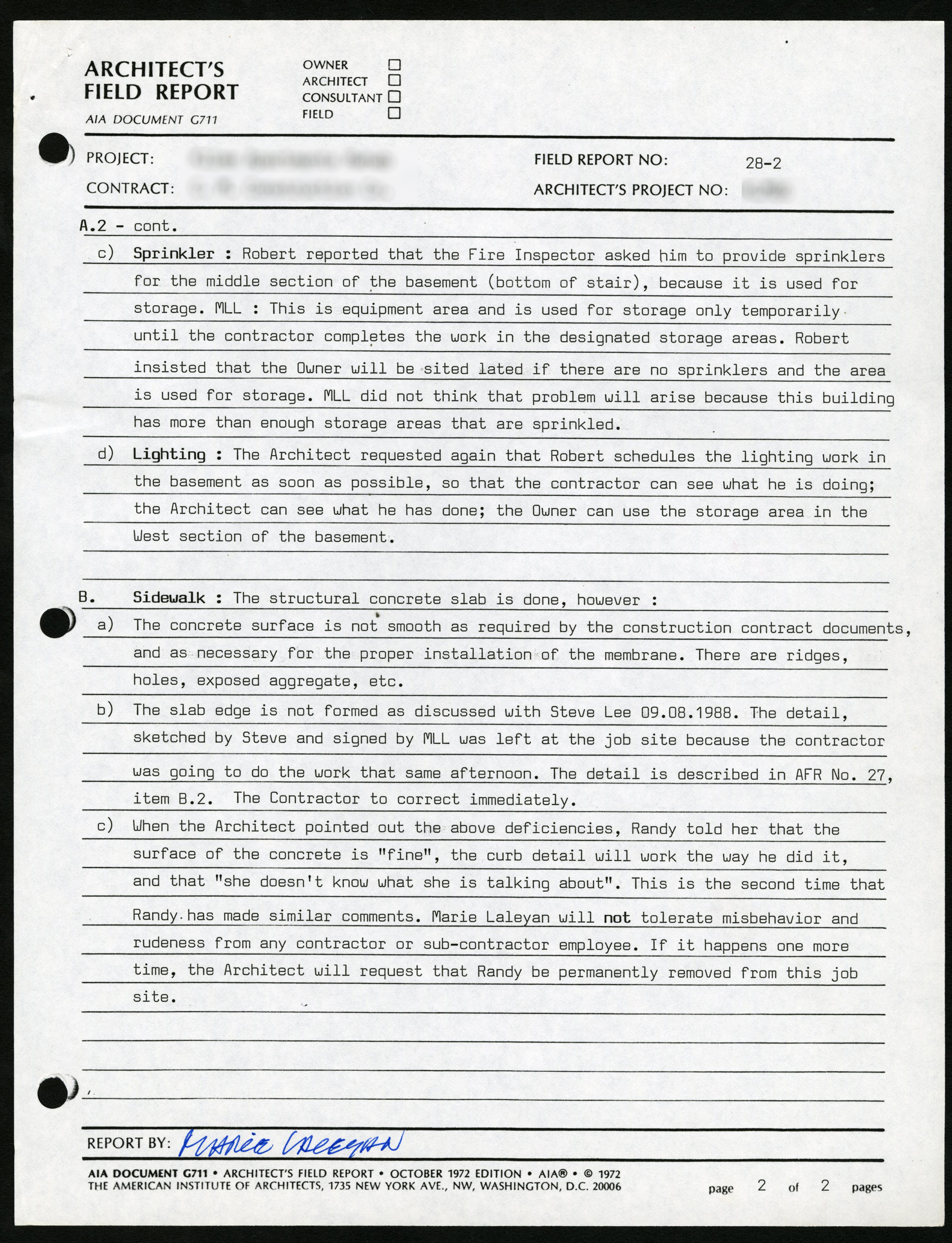

In reference to a letter from a contractor, Laleyan notes in section A that I do not challenge contractors. I administer the construction contract as required by my agreement and later notes occasionally contractors have disagreed with my interpretation of the contract documents, but you are the first who has challenged persistently my authority to interpret those documents and my right to make decisions, based on those interpretations.

In reference to a letter from a contractor, Laleyan notes in section A that I do not challenge contractors. I administer the construction contract as required by my agreement and later notes occasionally contractors have disagreed with my interpretation of the contract documents, but you are the first who has challenged persistently my authority to interpret those documents and my right to make decisions, based on those interpretations. The notes in the last section recount Laleyan’s experience ofbeing yelled at in front of a job superintendent, workers, and others. She goes on to mention that while she did not respond on grounds of professional behavior, she will not tolerate a project development supervisor undermining her authority with the contractor.

The notes in the last section recount Laleyan’s experience ofbeing yelled at in front of a job superintendent, workers, and others. She goes on to mention that while she did not respond on grounds of professional behavior, she will not tolerate a project development supervisor undermining her authority with the contractor. Laleyan notes that she would appreciate it if her designs were followed and not improved upon by the contractor.

Laleyan notes that she would appreciate it if her designs were followed and not improved upon by the contractor.