Although Thanksgiving has its roots in the 1620’s, the nationally recognized holiday in late Novemberis a product of the American Civil War.After two years of horrific fighting, Abraham Lincoln establishedthe national day of thanks in 1863, encouraging the public to remember those “who have become widows, orphans, mourners, or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife.” Despite the name, the first official Thanksgiving, planned for November 26, 1863, was not a day of celebration. As the Northern people preparedfor their proclaimed day of thanks, a battle raged in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Unaware of the upcoming holiday,

a twenty-nine year old man named John Henning Woods sat in chainsbehind Confederate lines, listening to the cannon fire. A resident of Alabama, husband to the daughter of a prominent slave-holder, and an outspokenUnionist, Woods had brought nothing but trouble to the Confederate Army of the Tennessee since his conscription in October of 1862. Thankfully, the highly unusual story of his life survives in the form of two journals, one diary, and a three-volume memoir that now reside in Special Collections.

A native of Missouri, Woods was born on July 4, 1834. At the start of the war, he was a law student at Cumberland University in Lebanon, Tennessee and husband to a wealthy Alabamian woman. The outbreak of conflict sent him back to Alabama, where he spent his days farming and arguing about the fate of the Union. He ignored his first conscription notice in May of 1862, refusing “to take part with the Slave-holders in this wicked rebellion.” However, the threat of imprisonment in October finally

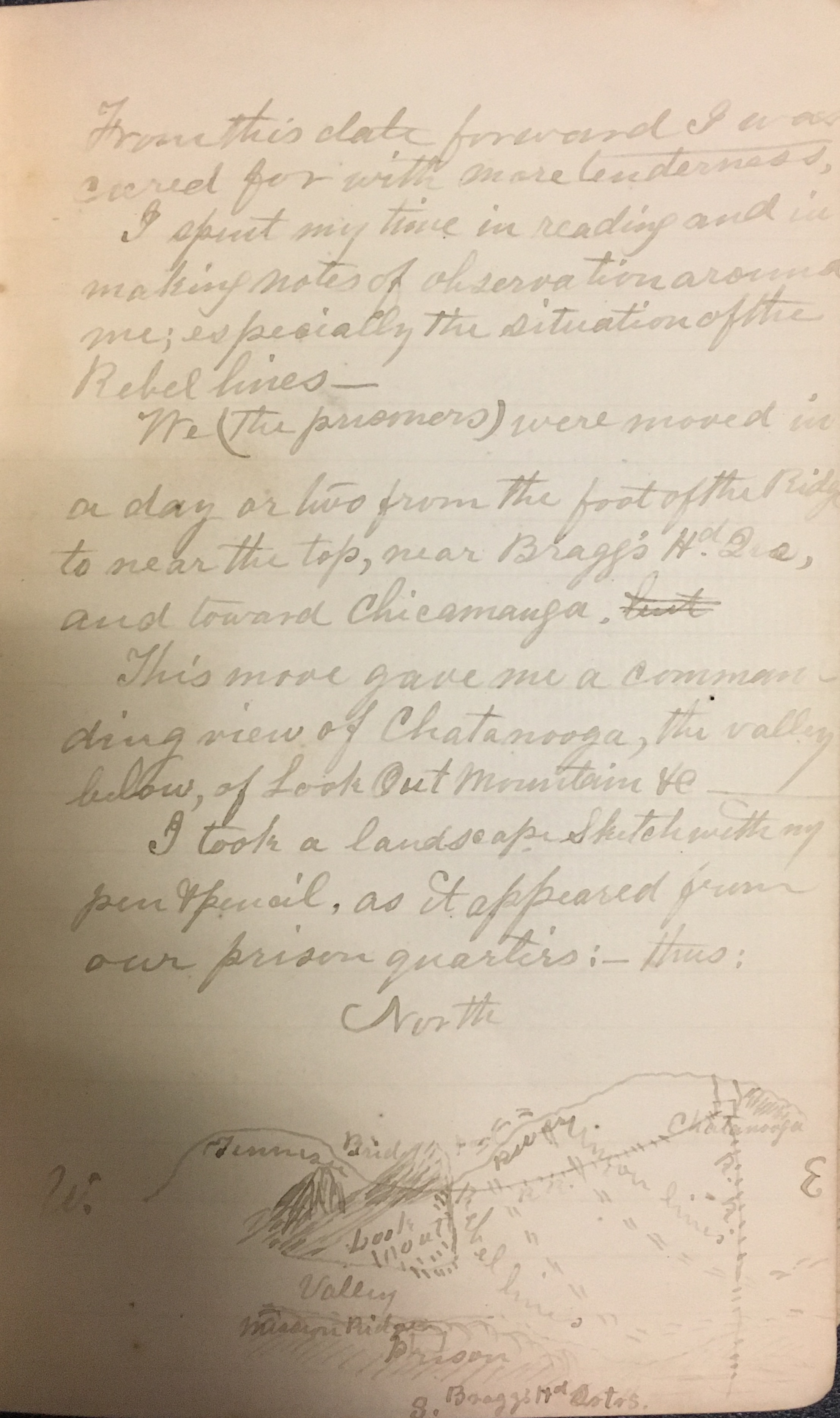

forced Woods into the ranks of army. His conscription only hardened his pro-Union sentiments,inspiring himand a few other conscripts to pledge “to work against . . . this unprovoked rebellion.” Their so called “Home Circle”attracted an increasingly large number of soldiers, eventually planning a mutiny to take place during a review parade. Before the plan could be enacted, the plot was betrayed and Woods was imprisoned to wait for a trial.His memoirs reveal his experience of the battles of Chickamauga and Chattanooga as a prisoner, wistfully overlooking the Union camps across the battlefield and wishing to walk across and “embrace the emblems of my country.”

Following his court martial in mid-December, Woods was informed that he was to be executed by firing squad the following day. His memoir includes a moving account of his reaction regarding the news:

I felt a flush through my system, upon the announcement to me, similar in feeling to that of an electric current from a Galvanic battery. . . . I told him I felt prepared to die whenever the proper authority should call for me, that I thought God’s power is above the power of the Southern Confederacy, and that, notwithstanding the apparent certainty of my pending execution, I believed he would provide means for my escape.

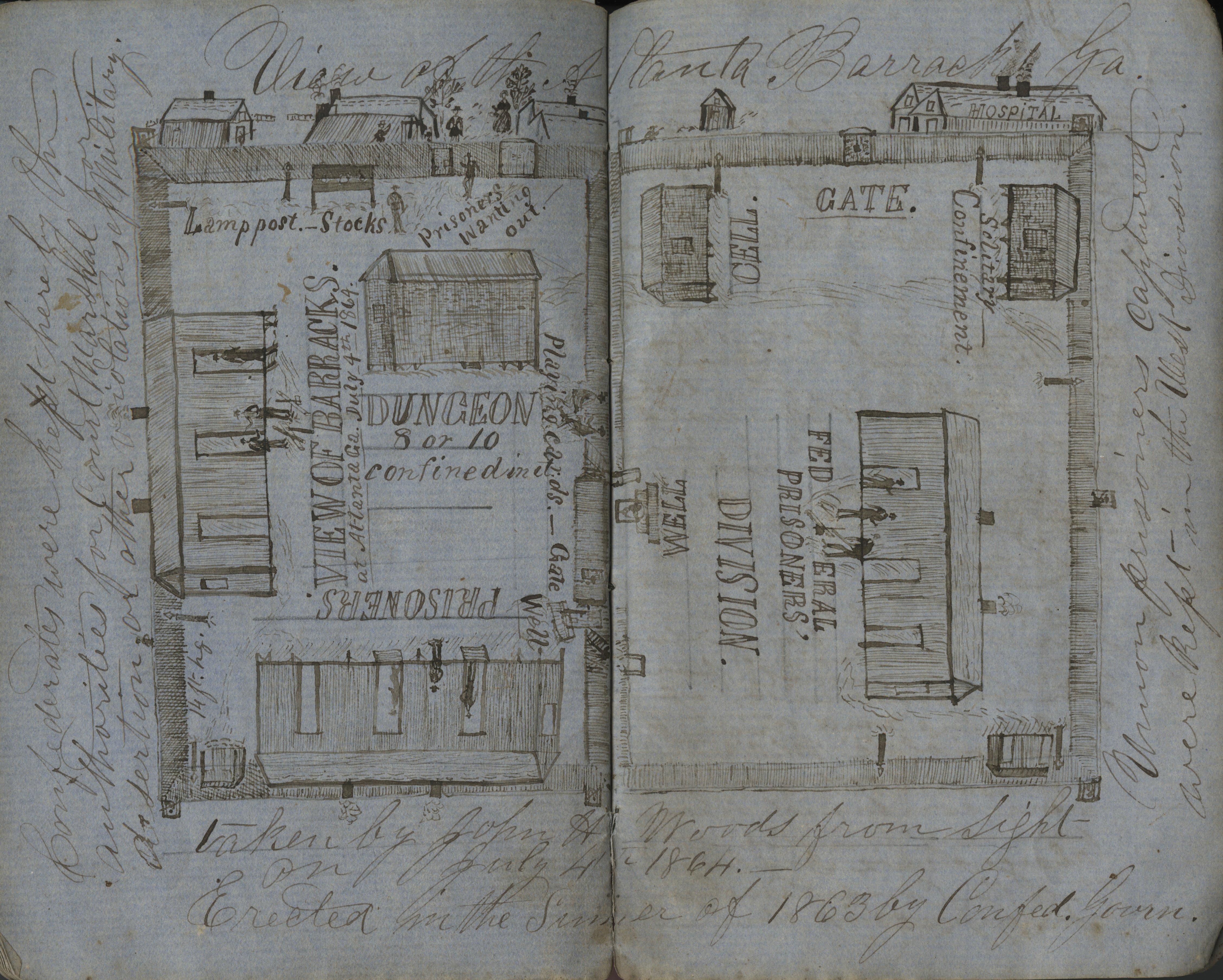

Woods’ faith in God was rewarded, as his execution was delayed at the request of General A.P. Stewart. He was then sent to Confederate prisons at Tullahoma, Wartrace, and Atlanta, awaiting his death once again. As he endured the horrors of imprisonment, his father-in-law and A.P. Stewart mobilized to secure a pardon from Jefferson Davis, a relief that did not come through until just two days before his proclaimed execution date. Following his pardon, Woods was assigned to building defenses around Atlanta until his eventual escape to Union lines, where he spent the remainder of the war as a clerk in the Union army. Unfortunately,the memoirs and journals reveal very little about his life following 1873; however, we do know that he died on March 5, 1901 and is buried in Lawrence Country, Missouri.

The detailed drawings, genealogical trees, and colorful prose that Woods left behind in these journals provide a unique look into the mind and experience of a Unionist Southerner during the war. It is clear through out that he wrote with the knowledge his unique place in history, making it invaluable to researchers. Though thecollection is brand new to Special Collections and therefore currentlyclosed to the public, it should be available fairly soon. In the meantime, have a happy Thanksgiving!

One thought on “Unionist in Southern Lines: The Life of John Henning Woods”