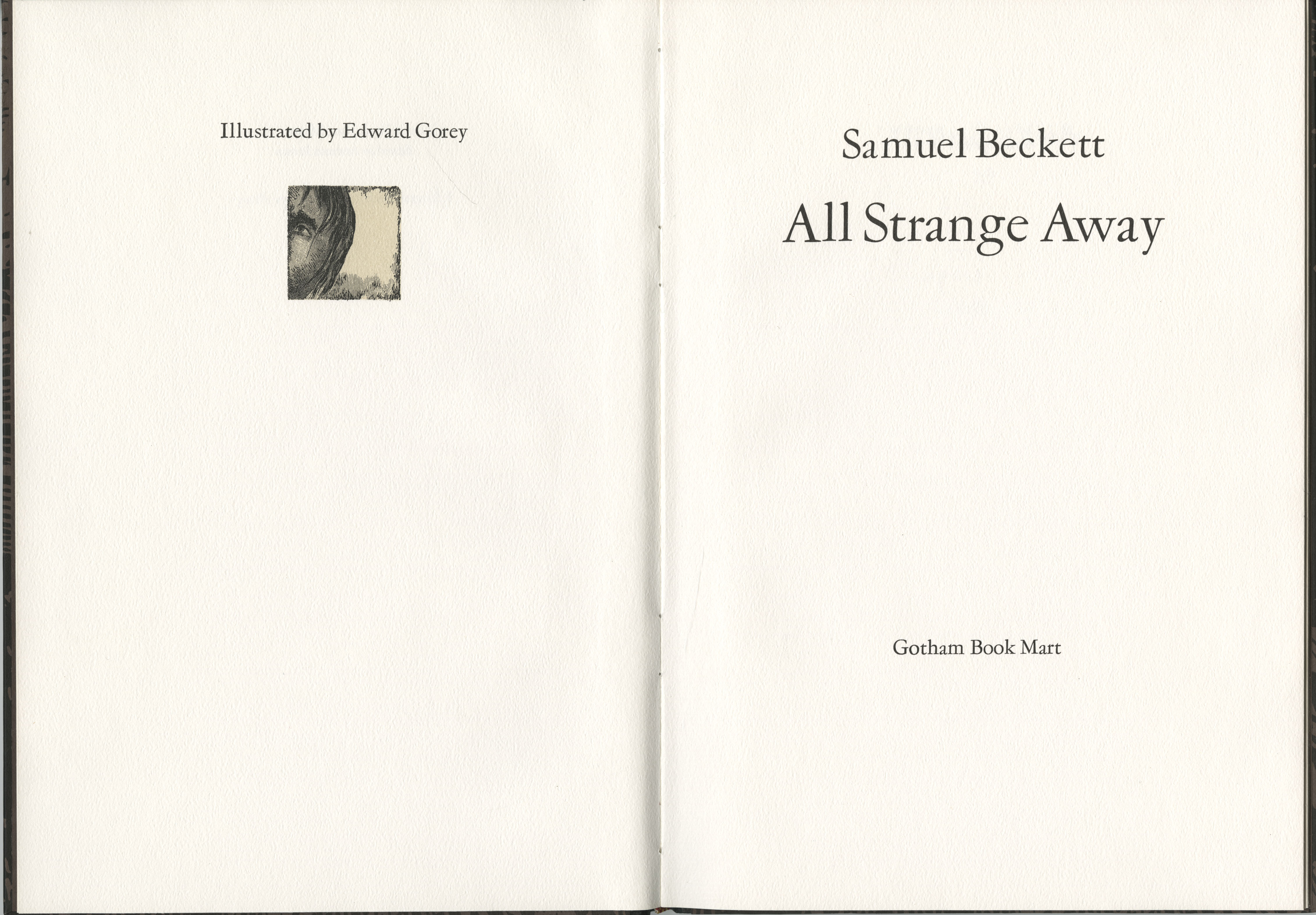

Beckett and Gorey at Gotham

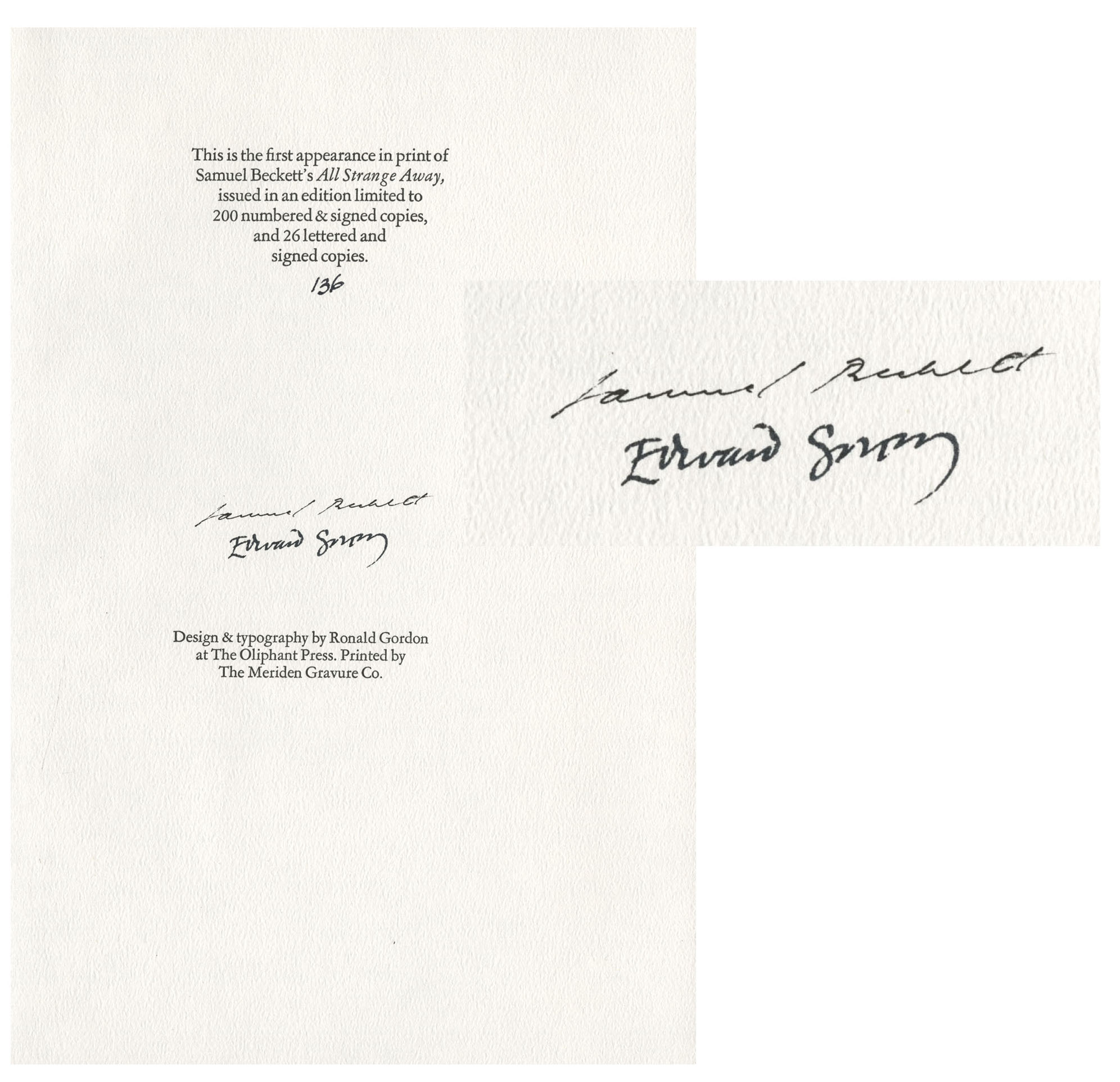

published by Gotham Book Mart, 1976

A few days ago, for no apparent reason, except, perhaps all the rain we’ve been having, I thought of a quote from a book by Samuel Beckett. Even though it had been about forty years since I first read it, I remembered the quote quite well. The in-and-of-the-world lyrical beginning was especially unusual for Beckett, in my experience. Still, I could not remember which book it came from. Beckett was a favorite in those days, and I had read a lot of his work (maybe more than was good for me) in a pretty short period of time. I didn’t think it was a particularly famous quote. For example, it wasn’t the end of The Unnamable:

. . . you must say words, as long as there are any, until they find me, until they say me, strange pain, strange sin, you must go on, perhaps it’s done already, perhaps they have said me already, perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story, before the door that opens on my story, that would surprise me, if it opens, it will be I, it will be the silence, where I am, I don’t know, I’ll never know, in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.

Nope, not that one. It wasn’t from the scene in Molloy that involves sixteen sucking stones, a number of pockets in a greatcoat (and trousers), and an attempt to place the stones in those pockets in such a way that Beckett’s character could most easily assure himself of sucking those stones in equal measure over time.

And it wasn’t the passage that begins with, “I can’t help it, gas escapes from my fundament on the least pretext” and ends with, “Extraordinary how mathematics help you to know yourself.” This is also from Molloy, and I’ll let you imagine what comes between those two fragments.

At about the same time I was trying to remember which book “my” quote came from, I realized that I’d never seen nor gone in search of a book by Beckett in Special Collections. This, of course sent me to the stacks (ok, to Addison, first) in search of Beckett. I know we have a large collection of modernist fiction, but over more than seven years . . . no call for Beckett. What I came up with surprised me. Not only was it a book I’d never seen before, it was one I’d never heard of. This required a bit of sleuthing.

The book, All Strange Away, was written in 196364, but not published until 1976 in the special edition we have in Special (naturally) Collections . . . an edition illustrated by Edward Gorey! (! The idea of a collaboration between Gorey and Beckett is amazing itself !) That’s a picture of Gorey at the top of this post, along with one of Beckett and the covers and spine from All Strange Away. Gorey wrote more than 100 books and illustrated many more. His dark sensibilities are often front-and-center in books like The Gashlycrumb Tinies in which twenty-six children whose names begin, in sequence, with each letter of the alphabet, have their deaths described (and illustrated) in one of twenty-six ways . . . all in rhyme, of course. (“M” is for Maud who was swept out to sea. “N” is for Neville who died of ennui.) Beckett’s text in All Strange Away begins:

Imagination dead imagine. A place, that again. Never another question. A place, then someone in it, that again. Crawl out of the frowsy deathbed and drag it to a place to die in. Out of the door and down the road in the old hat and coat like after the war, no, not that again. Five foot square, six high, no way in, none out, try for him there.

Like several of Beckett’s works from the mid-sixties, All Strange Away takes place in a bare space, or nearly bare. A stool is present, but the only dynamic seems to be imagination, that and the alternate presence and absence of light. Oh, and, maybe, the space changes size. In this text, the space is called the Rotunda and only one person inhabits it. In The Lost Ones, started by Beckett in 1966 and published in 1970, the space is a flattened cylinder 50 meters around with rubber walls 18 meters high. Two hundred people inhabit this space, which leaves about 1 square meter per person. Light and heat fluctuate, and there are ladders with which to climb the walls, and recessed spaces in the upper parts of the wall to occupy. I remember reading The Lost Ones, too.

Gorey’s illustrations, one or two per page, grace the margins of All Strange Away. Here are three of them:

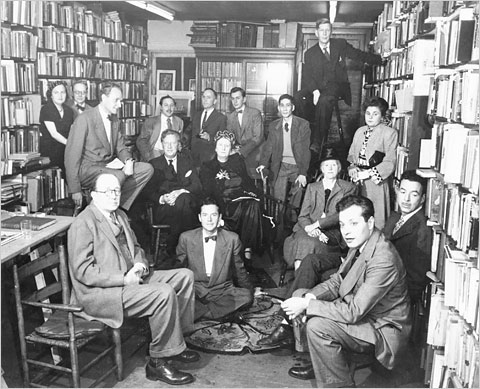

But wait, there’s more. How did Beckett and Gorey, who could be seen as an ideal illustrator for Beckett, ever get together in the first place? The key lies in the publisher, the Gotham Book Mart of New York. First, if you’ve never had the opportunity to visit the Gotham Book Mart, forget it. You missed your chance. This literary bookshop and meeting placethe kind of place that just doesn’t exist anymoreclosed in 2007 after operating continuously somewhere in midtown Manhattan (it did move a few times) since 1920. It was still enjoying its long heyday when I used to visit in the 1970s and 80s. The James Joyce Society, for example, was founded there in 1947 with the founder and owner of the shop, Frances Steloff, serving as the society’s first treasurer.

If you lived in New York and were interested in things literary, it was a regular stop. If you were visiting town, you’d go to see books that you’d see nowhere else, along with dozens and dozens of photographs of writers, often in the shop, perhaps standing where you were standing.

Although Gorey’s first book, The Unstrung Harp was published in 1953 and The Doubtful Guest (1958), did much to establish his standing among a wider readership, it was his friendship with Andreas Brown, owner of the Gotham beginning in 1967, that really propelled his career. Actually, the Gotham Book Mart published more than a dozen of Gorey’s books, exhibited his illustrations, and, generally, brought him and his work to something like a mass audience. (Gorey’s annimation appears every time Mystery! is introduced on PBS.) One presumes that Brown may have brought the Beckett to Gorey, but I know of no details on the matter. I now know that Gotham Book Mart also published another collaboration between the two, Beginning to End, in 1989, just before Beckett died.

And . . . did I mention that the book is signed by both Beckett and Gorey . . . and numbered! Our copy is number 136 of 200.

All in all, this was quite the find. You never know what will show up in Special Collections until you have reason to look. (Today, I found out that we have a first [1854] edition of Thoreau’s Walden. But that’s a story for another day.)

So what was the quote that provided the germ for this post? It was from a work of Beckett’s called The End, written in 1946:

The earth makes a sound as of sighs and the last drops fall from the emptied cloudless sky. A small boy, stretching out his hands and looking up at the blue sky, asked his mother how such a thing was possible. Fuck off, she said.

How do you top that on a rainy day?

Posted originally by marc9.

Serialization of the 19th Century Novel

In the 1830s, a new trend began in publishing (a “novel” idea, if you will!): Novels started to appear in newsstands. But rather than publishing in a large, cumbersome form that one couldn’t carry easily, they were issued in small, portable, serialized segments. Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers was the first to appear this way in print, but he wouldn’t be the last author to try it (a bit more on that in a moment). For authors AND audiences, this format had a number of advantages. For authors, it meant they could begin to sell a story before it was completed, that they didn’t actually have to have everything plotted out, and they had a little more time to write. For audiences, it meant following a story as it unfolded (rather than waiting for a full novel), a more dramatic reading experience that was drawn out by having to wait, talk with people, and guess, and easier to access the literature of the era. Novels were expensive, but a single serial volume could be purchased for a shilling and passed from person to person. Of course, this does mean the volumes were ephemeral, on cheap paper, and not meant to last. Lucky for us, some of them survived. Special Collections is home to a number of serialized novels, either in complete or mostly complete form.

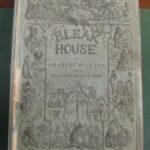

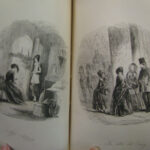

The first of two we’re sharing today is Charles Dicken’sBleak House, originally published in 20 parts (though two are combined, so it’s only 19 volumes) between 1952-1953. (Due to the fragile nature of the publications and the bulky nature of their housing, I had to photograph, rather than scan these items. Apologies for the occasionally blurry quality and/or fingertips!)

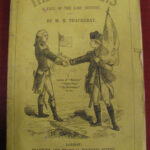

The second example is William Thackeray’sThe Virginians, published in24 parts between November 1857 to October 1859.

Other than the obvious fact that these are different authors and different novels, there’s something else unique about the serialized novel: when a novel was issued independent of another publication (the parts of many serialized novels appears within literary magazines of the time), authors had their own color for a cover. It made new parts stand out on shelves and caught potential readers’ eyes. Dickens’ covers were blue, Thackeray’s were yellow. George Eliot’s covers were green, and from what I’ve found so far, Anthony Trollope’s were brown (at least those from the same publisher). I think I recall another writer having purple covers, but I haven’t been able to come up with who that was. If you know, let me know in the comments!

A little later in the 19th century, another form of the serialized book emerged: the “three-volume” novel (aka the “three-decker” or my favorite, the “triple-decker”). Longer novels like Henry James’ The Portrait of a Lady or George Eliot’s Mill on the Floss both appeared in this format (we have a copy of the latter in our collection). The triple-decker afforded some of the convenience of the serial in a more condensed form and by the time it was popularized, book-making processes (and consequently book-buying) had become cheaper. On the other hand, both established and newauthors of the age began to make their living this way, many of them through sensational, overly-dramatic tropes and as a result, in some literary circles, the triple-decker took a lot of criticism and mockery. As one of Oscar Wilde’s characters remarks in one of my favorite plays,The Importance of Being Ernest, “It [a baby carriage] contained the manuscript of a three-volume novel of more than usually revolting sentimentality.” (Wilde himself published some of his writings in serial format in literary journals of the time, though he didn’t produce anytriple-deckers.)

Whether you’re an English major, a literature lover, or just curious about unique formats of books, you’re always welcome to pay us a visit to see our serial sets, three-deckers, and more!

Posted originally by archivistkira.

The great big world of miniature books

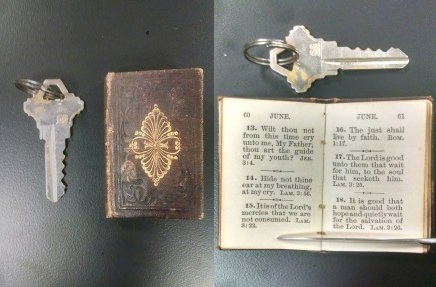

When I arrived in fall of 2014 as a new employee, the department had an exhibit on display featuring miniature books from the 19th and 20th centuries. It was a perfect introduction to the curious, strange, and unexpected variety of materials that I would come to find in Special Collections.

The Library of Congress defines miniature books as works 10 centimeters or less in both height and width, which is a little under 4 inches. The Miniature Book Society maintains a more circumscribed definition of no more than three inches in height, width, or thickness. Within these parameters, American collectors recognize several sub-categories, including macro-mini (3-4), miniature (2-3), micro-mini (1-2), and ultra-micro-mini (less than 1). Often intricately bound and printed, miniature books are considered a testimony to the printers skill.

According to the American Antiquarian Society, the oldest miniature books were produced on clay tablets in Mesopotamia; scholars and monks from ancient Egypt to medieval Europe produced miniature manuscripts by hand long before the invention of the printing press. The Diurnale Mogantinum, published in 1468 by Johann Guttenbergs assistant Peter Schoffer, is the earliest example of a traditionally printed miniature book. The tiny texts became particularly fashionable in America during the 19th century as a portable and novel way to carry decorative and instructional texts. The most popular books in this time were religious tracts, advertisements, and childrens books.

Miniature books experienced a new wave of popularity in the 1970s as artists and independent publishers explored new methods for binding, printing, and distributing. Like their full-sized counterparts, modern miniature books are incredibly diverse in construction and purpose, ranging from plain and conventionally bound to elaborately illustrated pop ups, scrolls, and accordions.

Although Special Collectionsdoes not collect tiny books on the scale of some passionate hobbyists, we have accumulated a limited but fascinating assortment of miniatures over the years. Highlights include an ornithology text published in 1810; several 19th and 20th century childrens books; a collection of Lincoln speeches reprinted in the mid 20th century; curios, art books, and poetry chapbooks by American micro-presses in the 1960s and 1970s; a handful of foreign language texts; and an edition of Five Articles by Chairman Mao Tse-Tung.

We also have several tiny books about food, which you can read more about on Whats Cookin @Special Collections, the blog for our History of Food & Drink Collection. If you want to learn more about the history and making of miniature books, check out Louis Bondys Miniature books: their history from the beginnings to the present day available in the Newman Library and Peter Thomas More making books by hand: exploring miniature books, alternative structures, and found objects available in the Art + Architecture Library.

Posted originally by archivistwinn.

The Ill-fated Voyage of the U.S.S. Jeannette, 18791881

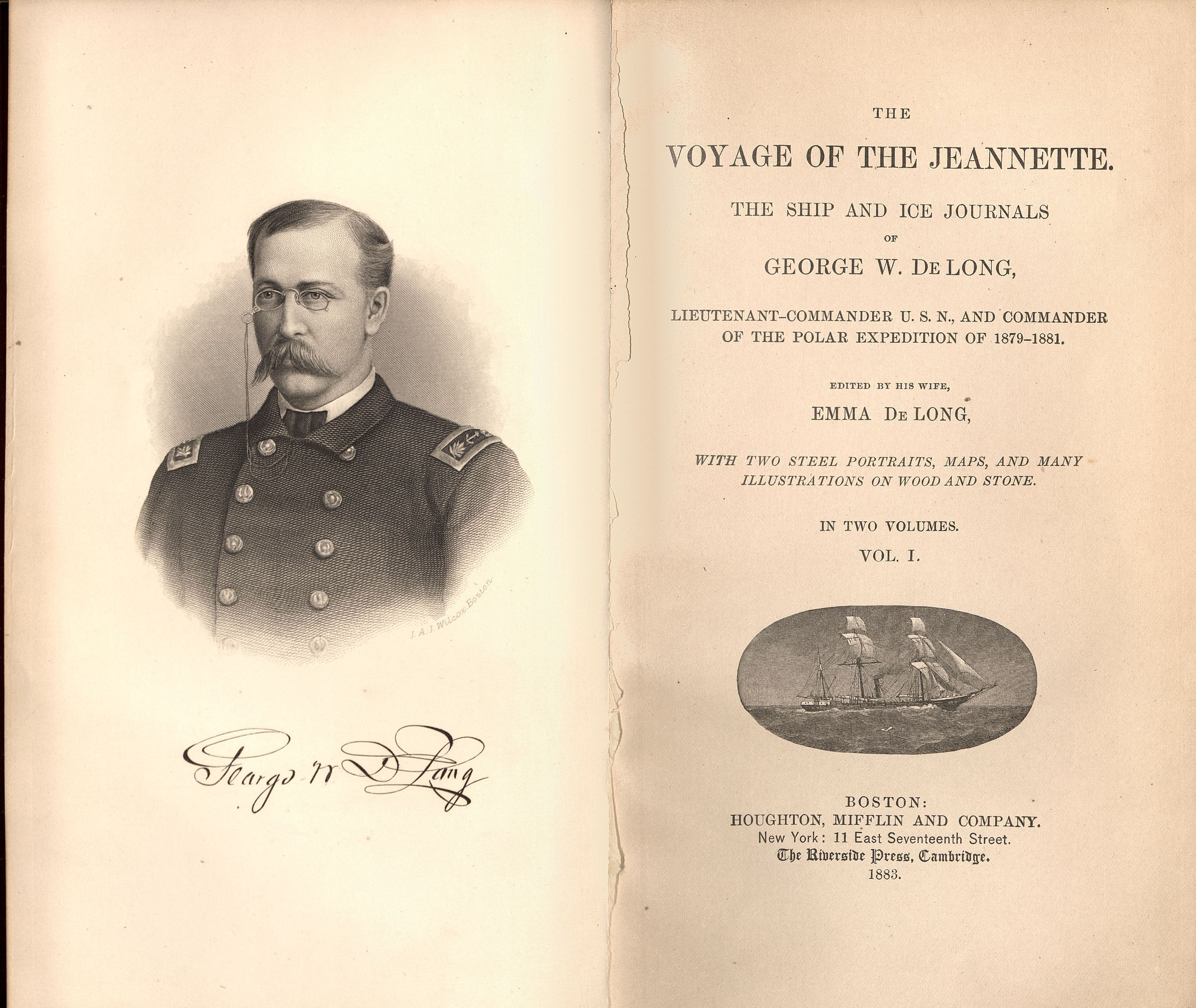

As I was scouting the bookshelves a few months ago in search of something to inspire a new exhibit, I came across two volumes of “The Voyage of the Jeannette: The Ship and Ice Journals of George W. De Long, Lieutenant-Commander U.S.N., and Commander of the Polar Expedition of 1879-1881. I was familiar with several 19th-century polar expeditions, particularly that of John Franklin, which left England in 1845, never to return, but De Long was unknown to me. In the end, I found first-hand accounts of many voyages of discovery, which led to the idea to assemble an exhibit on the themes of Discovery, Travel, and Exploration, but it was the Jeannette with which I began and whose story continues to enliven my curiosity.

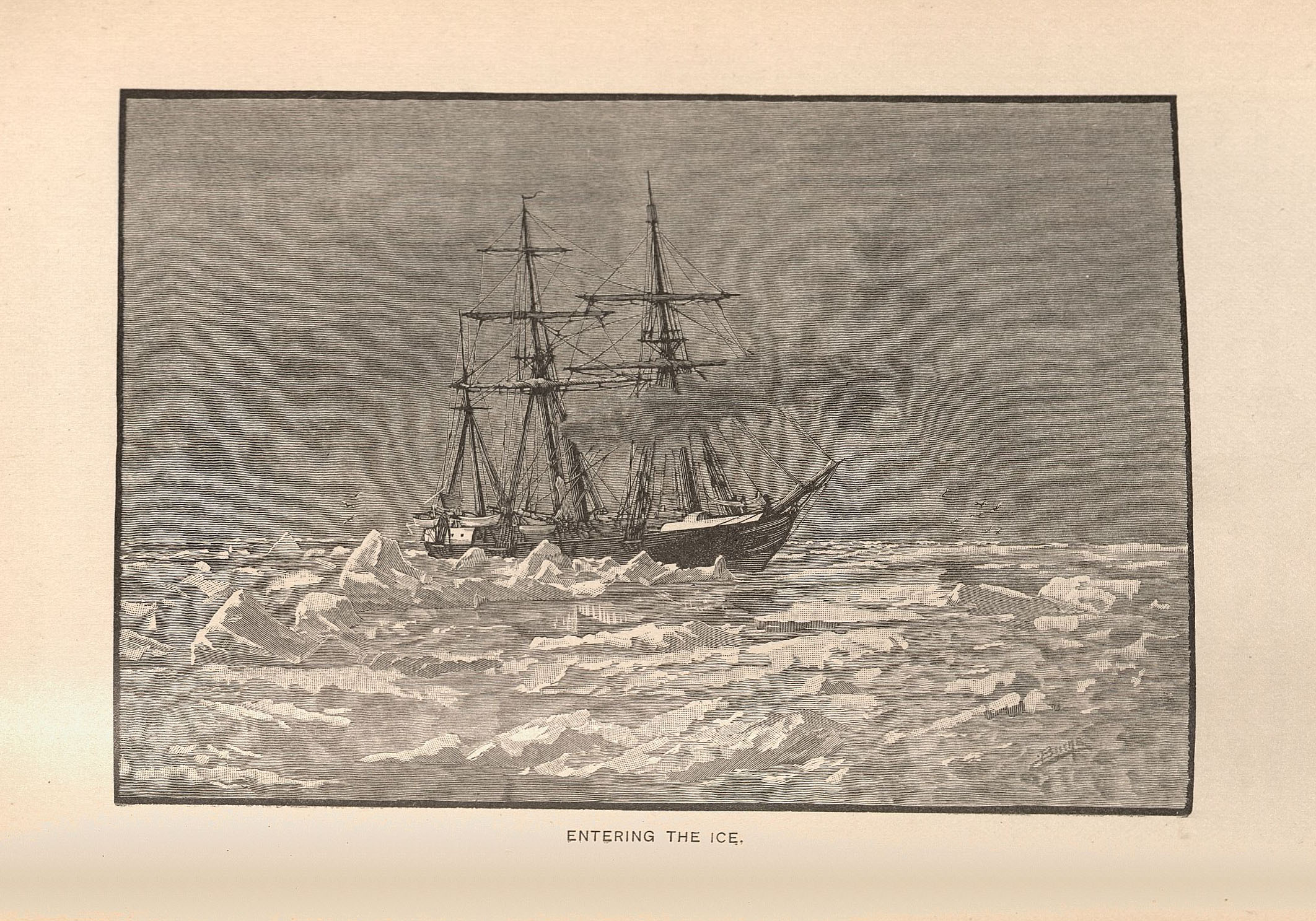

When the U.S.S. Jeannette set out from San Francisco on 8 July 1879 with 33 men aboard, including its commander, George Washington De Long, its mission was to reach the supposed Open Polar Sea, attain the North Pole, and to record all manner of scientific observations along the way. Initially built as a gunboat for the British Navy and named Pandora, it had three masts and was equipped with a steam engine and propeller. The ship had passed into private hands and successfully survived two trips to Greenland before James Gordon Bennett Jr., owner of the New York Herald bought her, renamed her Jeannette, and had her structure massively reinforced, all in preparation for the polar mission that De Long would command. She would carry provisions to last three years.

By 6 September of that year, the Jeannette was locked in the ice, sooner and further south than anticipated. Through disappointment and routine, mostly good spirits prevailed. On 28 October, De Long wrote:

I think the night one of the most beautiful I have ever seen. The heavens were cloudless, the moon very nearly full and shining brightly, and every star twinkling; the air perfectly calm, and not a sound to break the spell. The ship and her surroundings made a perfect picture. Standing out in bold relief against the blue sky, every rope and spar with a thick coat of snow and frost; she was simply a beautiful spectacle.

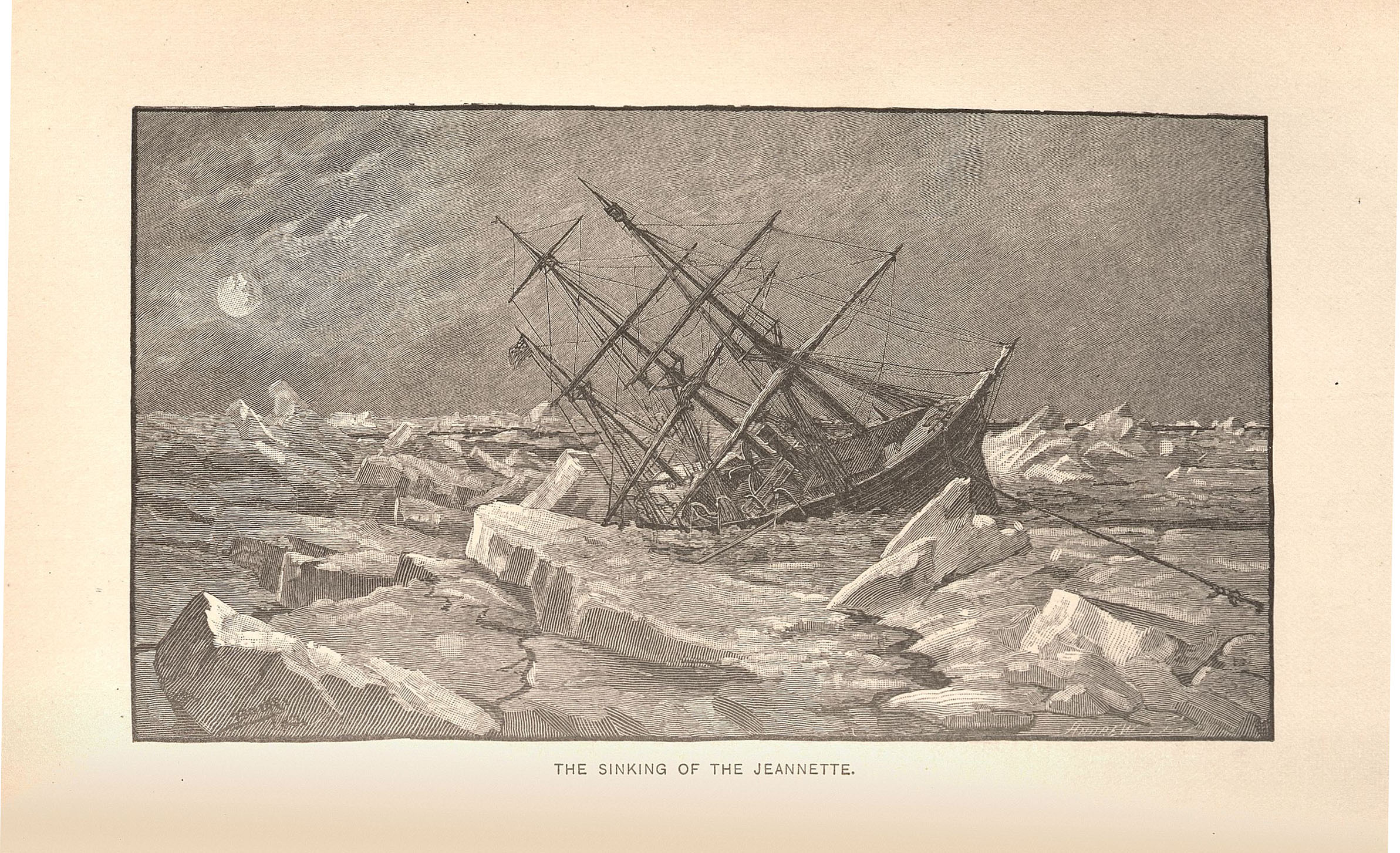

The Jeannette would drift in the ice in a northwesterly direction through the frozen summer of 1880 and into the spring of 1881. On 11 June–nearly two years after leaving San Francisco–just after midnight, as De Long wrote, the ice suddenly opened alongside and the ship righted to an even keel. For the first time in twenty months, the ship was afloat. Cruelly, some forty hours later the situation had changed:

At four P.M. the ice came down in great force all along the port side, jamming the ship hard against the ice on the starboard side of her, and causing her to heel 16 to starboard. From the snapping and cracking of the bunker sides and starting in of the starboard ceiling . . . it was feared that the ship was about to be seriously endangered. . . . Mr. Melville . . . saw a break across the ship . . . showing that so solidly were the stern and starboard quarters held by the ice that the ship was breaking in two from the pressure upward exerted on the port bow of the ship.. . . At five P.M. the pressure was renewed and continued with tremendous force, the ship cracking in every part. The spar deck commenced to buckle up, and the starboard side seemed again on the point of coming in.

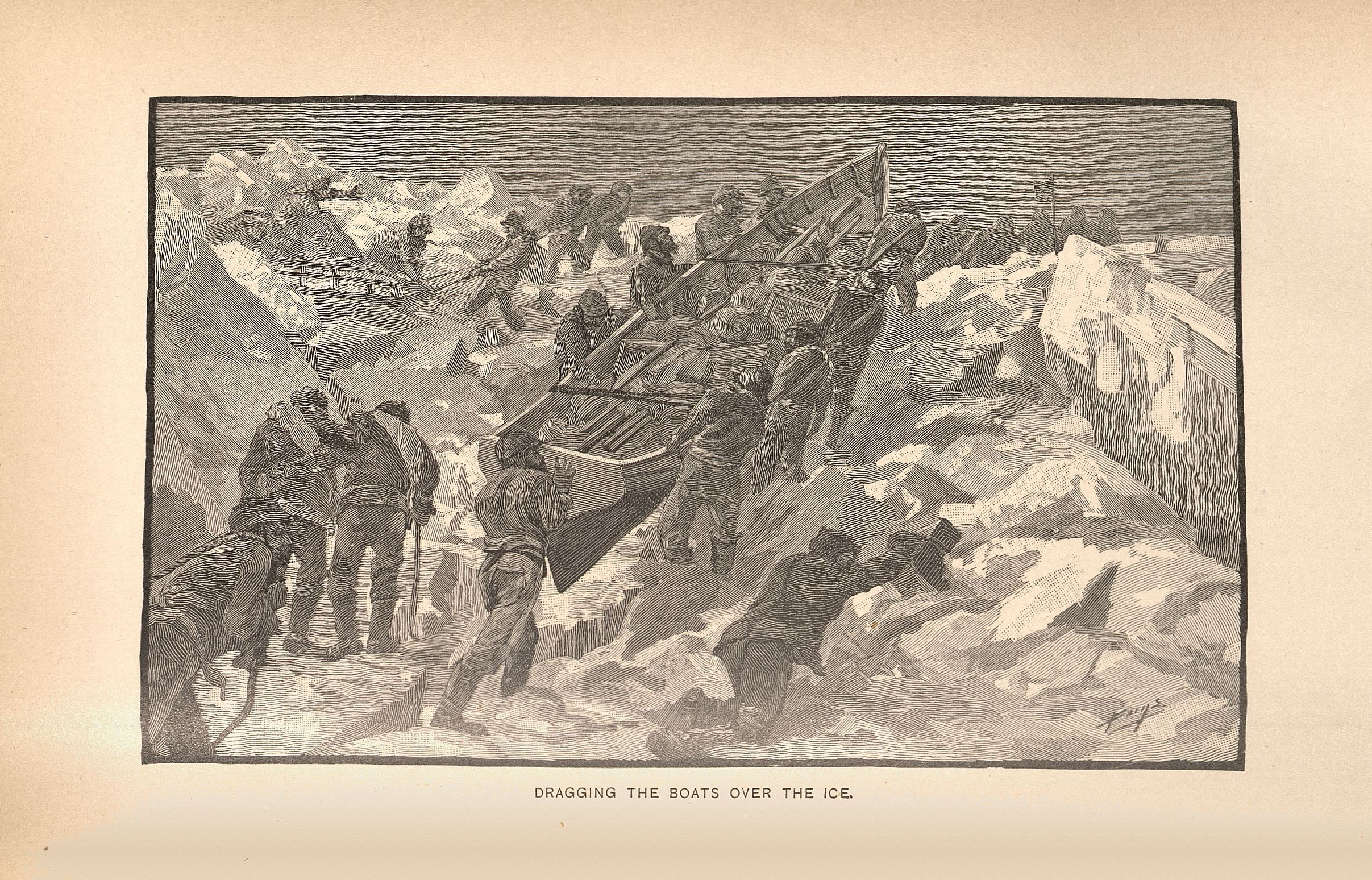

By 6 PM. the Jeannette began to fill with water and as provisions were removed, the ship heeled 30 to starboard. The starboard side had broken in and at 8 PM all hands were ordered off the ship. At 4 AM, the ship went down. They had reached just beyond 77 N latitude, some 700 miles south of the pole, and would head southwest hauling their boats and equipment towards the Lena River on the Siberian coast.

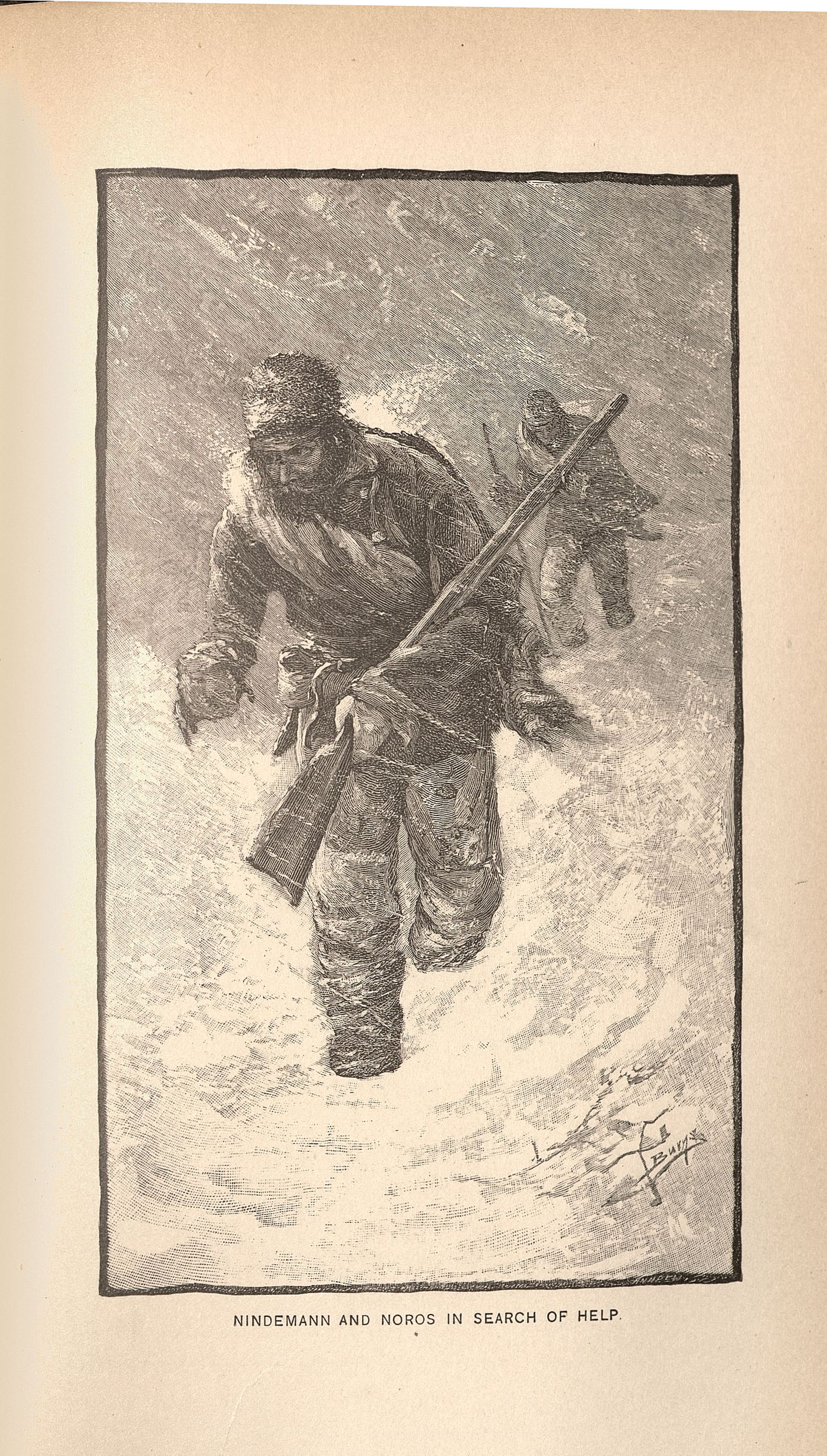

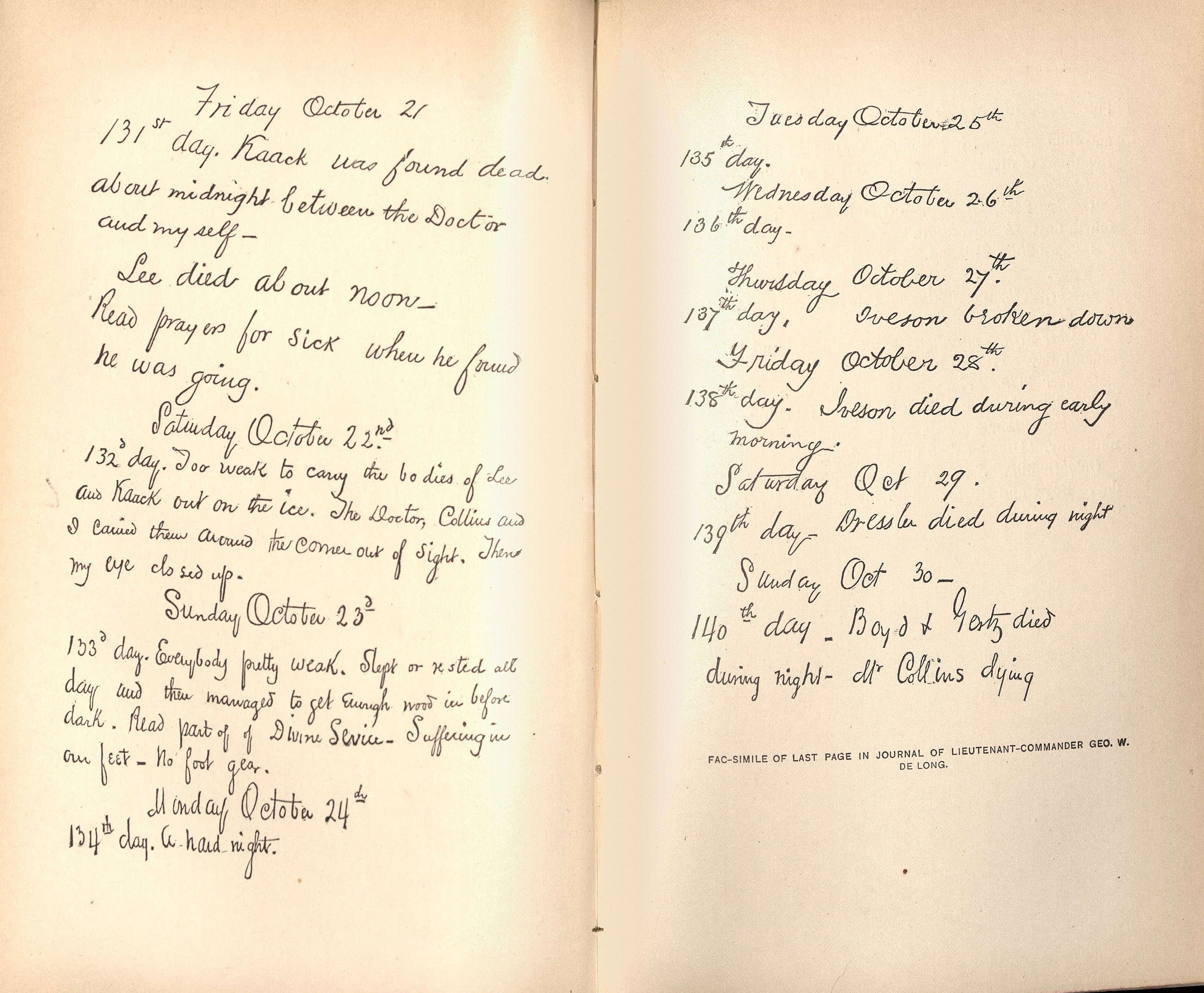

Upon reaching open water 91 days later, the crew boarded three boats on 12 September. A gale separated the three and one boat was lost. De Longs boat, carrying 14 men, reached the marshy Lena delta on 15 September and would soon be abandoned. On 9 October, with the entire party suffering from starvation and exposure, a weakened De Long sent two men ahead in search of help. These two men, Nindemann and Noros, found a small group of hunter-fisherman on 22 October, who took them to the larger settlement they sought. The third boat, commanded by George Melville with eleven aboard, reached the delta on 14 September, nearly 100 miles from the first group, but on a navigable branch of the river. Five days later, they found a fishing camp. Neither Melvilles group nor Nindemann and Noros were able to mount a rescue for De Longs group, though on 2 November, they did find each other. George W. De Long, however, had written his last log entry on 30 October:

One hundred and fortieth day. Boyd and Grtz died during the night. Mr. Collins dying.

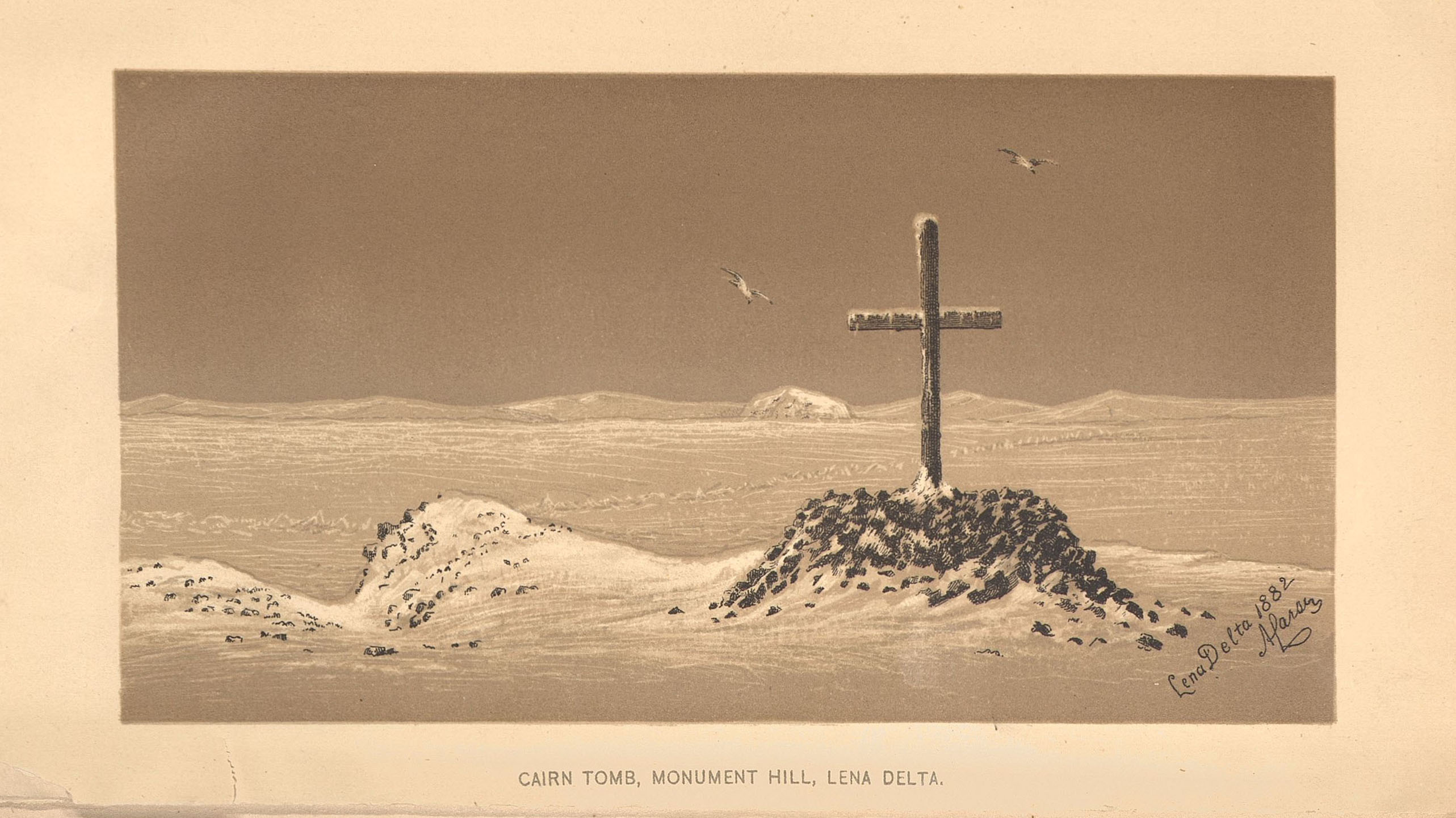

Melville continued the search for his comrades and on 13 November, he found the Jeannettes log books, instruments, and other items that De Long had buried on 19 September. It wasnt until the following spring, on 23 March 1882, that Melville and Nindemann found the bodies of De Long and two other members of his party, then those of the remaining seven. One mans body was never found. They also found the ice journal that De Long had kept and which recorded the journey they had taken since the Jeannette was lost. All ten bodies were placed in a makeshift coffin and interred in a cairn on the highest point in the area.

George Melville arrived in New York on 13 September 1882 and brought De Longs papers, journals, and personal effects to his widow, Emma.

By Act of Congress, the remains of De Long and the nine crew were ordered returned for burial in the US. On 20 February 1884, after a 12,000 mile journey westward, they arrived in New York. De Long and six others were buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. On 18 June 1884 a broken box bearing the name Jeannette and other items from the ship were found off the southern coast of Greenland, thousands of miles east of Jeannettes final location. Having made their own journey, these items gave new support to the theory of trans-Arctic drift.

So, this was the story that was the spark for an exhibit that will soon go up, one that will present materials offering a range broader than that of polar exploration . . . but, interestingly, the Collection has several accounts of trips using various means to arrive at various poles. Watch for it:

Posted originally by marc9.

Legacy of Dayton Kohler

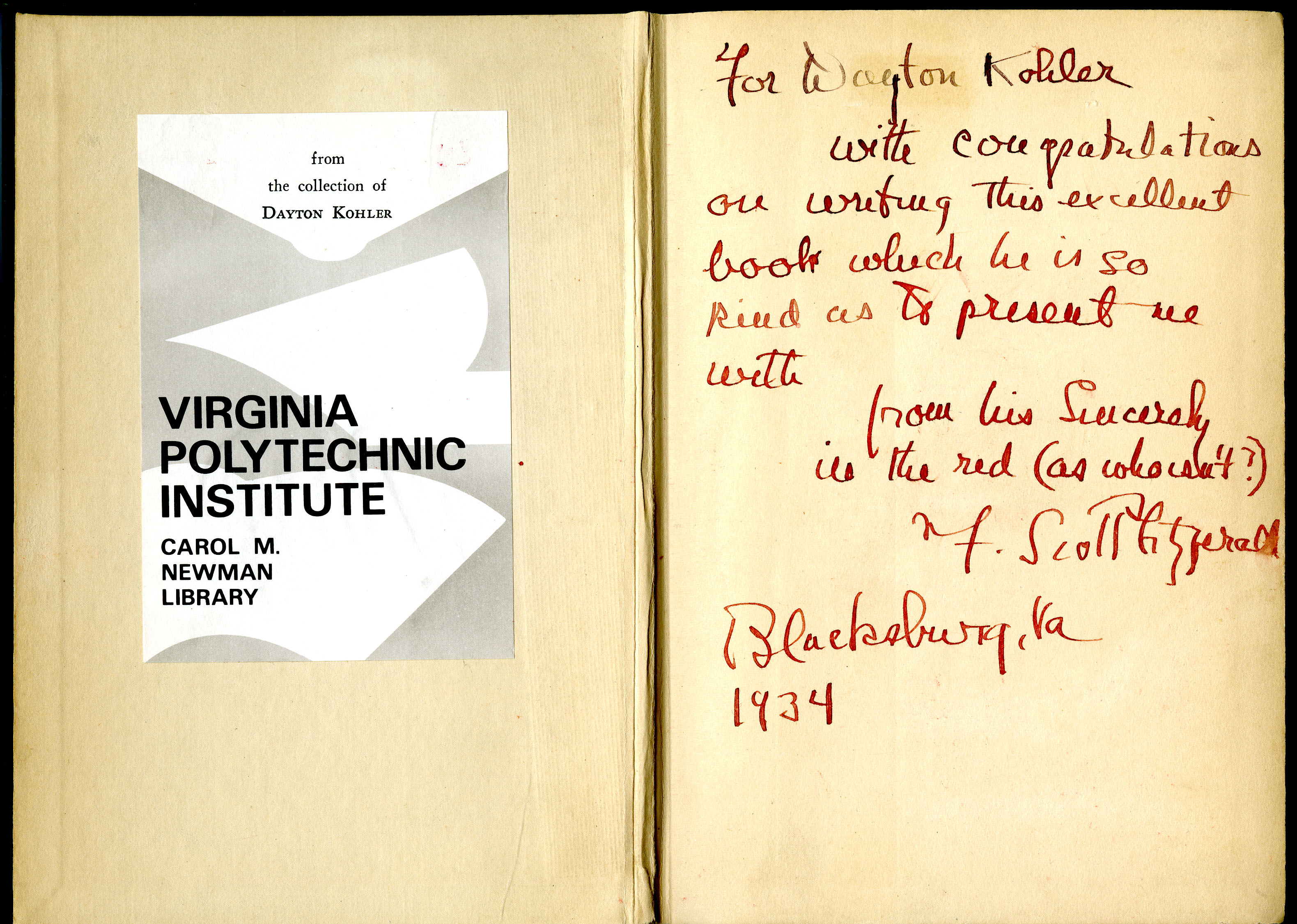

If you have an interest in modernist literature and have, on occasion, requested Special Collections’ copies of such worksespecially by American writers of fiction, though not exclusivelyyou may have discovered the bookplate shown above with a startling frequency. “From the Collection of Dayton Kohler . . . Virginia Polytechnic Institute . . . Carol M. Newman Library” appears time after time in books by many of the great writers of our time in the Rare Book collection.

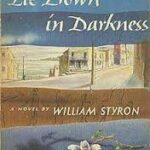

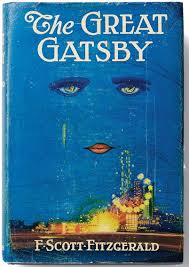

When I first started working here, just about five and a half years ago, as I came upon first editions of Faulkner, Hemingway, Cather, and Fitzgerald; then Virginia Woolf, D. H. Lawrence, and Joseph Conrad; Saul Bellow, Katherine Anne Porter, Eudora Welty, James Thurber, J.D. Salinger, Reynolds Price, William Styron, and more, I kept noticing the same bookplate. All first editions, several of them signed by the author. Who was Dayton Kohler?

Select first editions from the collection of Dayton Kohler

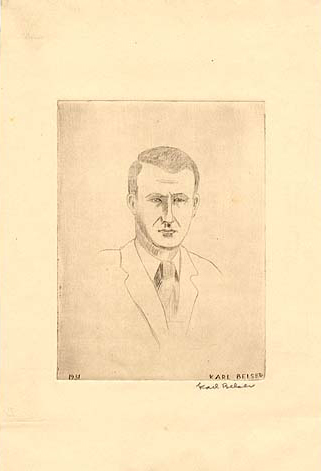

Kohler was Professor of English at Virginia Tech. He retired in 1970 after arriving at this institution as an Instructor in 1929. Born in 1906 and a graduate of Gettysburg College, he received his master’s degree from the University of Virginia the same year he came to Blacksburg. In 1931, Karl Belser, a colleague in the Department of Architectural Engineering drew a sketch of Kohler (shown above) that is housed, along with several other prints and drawings, in the Karl Jacob Belser Illustrations, 1931-1932, 1938, n.d., also at Special Collections. Kohler’s own collection of papers is also on hand. It includes an extensive correspondence with authors and other critics of the time, much of which relates to various literary essays and reviews.

Dayton Kohler died in 1972, but not before arranging for a collection of his booksincluding many 20th-century first editionsto become part of Special Collections. In fact, former director of Special Collections Glenn McMullen said in a June 1990 Roanoke Times and World News article that acquisition of Kohler’s book collection was “the first major acquisition” for the new department that had only formed in 1970. A May 21, 1971 memo to then-library director Gerald Rudolph reports that 1095 books were received from Professor Kohler some ten days earlier. The list that accompanies the memo shows only authors and quantity, with no detail regarding title and/or edition. But, in addition to the names referenced above, the list includes William Carlos Williams, John Dos Passos, Truman Capote, Henry James, Ezra Pound, James Joyce (a trip to the shelves indicates the 1930 edition of Ulysses, not the 1922 first edition, was Kohler’s), and a total of 27 Hemingways and 38 Faulkners(!), plus much, much more. What a tremendous legacy for the Library and its patrons to use and enjoy. I’m sure there are still more terrific editions in the collection that I haven’t yet seen. To close (almost) this post, I’ll leave you with one more that I did find:

Lastly, if any alumni who may remember Professor Kohler read this post and wish to tell us more about him, please consider leaving a comment below. We’d be pleased to add them to this post. Thanks!

Posted originally by marc9.

A Rare Bit of Whitman: Leaves of Grass, 1882, The Author’s Edition

If you’ve never delved into the publishing history of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (I had not, until recently), it can be quite an interesting and involved pursuit. One small, but very fine part of the story is represented by one of the several editions of the book that may be found in Special Collections.

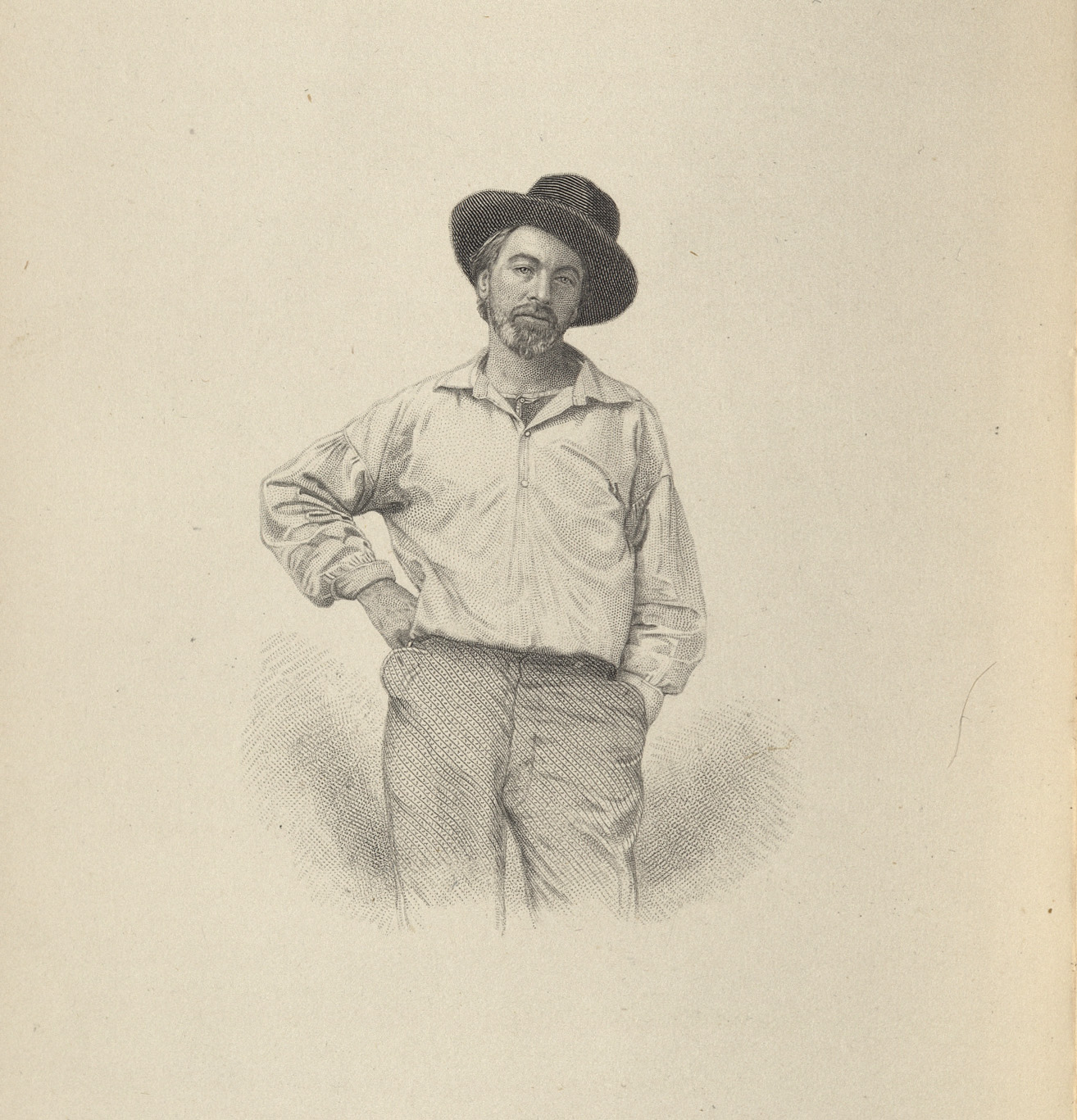

In 1881, some twenty-six years after the first edition of Leaves of Grass appeared, the prestigious Boston publisher James R. Osgood & Co. approached Whitman with an offer to publish a new sixth edition. Whitman accepted and, ever the printer and bookmaker, set out to oversee the production details of the new volume. He had reacquired the John C. McRae/Samuel Hollyer 1855 steel plate engraving of himself that had been used, first, in the original edition and, again, in the 1876 printing of the fifth edition. He would include it in the new edition, where it would be placed not as a frontispiece, as before, but within the text, opposite the opening of “Song of Myself.” Whitman also planned to have all of his finished poemsreordered, rearranged, and regroupedincluded in the volume under the title, Leaves of Grass. All seemed to be going well, and in October 1881 the book was released. The first thousand copies sold and a second printing was ordered. Special Collections does not have a copy of the 1881 Osgood sixth edition . . . but the story only gets more interesting.

On 1 March 1882, in part at the urging of the The New England Society for the Suppression of Vice, Oliver Stevens, District Attorney for Boston, wrote to Osgood & Co. to advise them that Leaves of Grass was obscene literature and that they would do well to suspend publication and to withdraw and suppress the book. After an unsuccessful negotiation between Osgood, the authorities, and Whitman, Osgood, under threat of prosecution, wrote to Whitman on 10 April of their decision to cease circulation of the book. In May, Whitman received from Osgood all of the plates, unbound sheets, and dies of Leaves of Grass, along with a $100 payment.

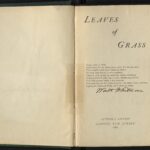

Reports vary as to whether Whitman was left with 100 or about 225 complete sets of unbound sheets, but there is no doubt about his next move. While seeking a new publisher for his work, Whitman had a new title page printed and bound together with these sheets. The new title page identified the volume as “Author’s Edition” and added the notation, “Camden / New Jersey / 1882.” The book was bound in green cloth rather than the yellow of the Osgood edition. Several accounts of the editions of Leaves of Grass fail to mention this short run edition.

Before the end of June 1882, Whitman had reached an agreement with Rees Welsh, a Philadelphia company, to receive the plates and publish the book. The Rees Welsh edition of 1882 (a copy of which is also available in Special Collections) sold extremely well, perhaps due to the publicity generated by the unpleasantness of being “banned in Boston.” One source reports that it went through several printings and had sold almost 5,000 copies by December of that year. Another report says the first limited printing of a thousand copies sold in two days; another claims between two and three thousand sold on a single day!! The Osgood plates would pass quickly from Rees Welsh to publisher David McKay, and would provide the basis for all further editions of Leaves of Grass published in Whitman’s lifetime.

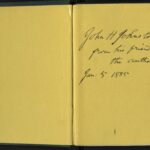

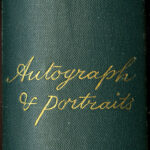

But the Author’s Edition of 1882 is the subject of this post. Again, it is one of many editions of Leaves of Grass in Special Collections. Our copy is signed by Whitman on the title page that was printed specifically for this edition. At between 100 and 225 copies produced, it is among the rarest of editions of Leaves of Grass. (Of the more significant 1855 first edition, 795 were printed and 158 copies are known to exist, according to a 2006 study by Ed Folsom. Others set the number at closer to 200.) The spine reads “Author’s / Edition / Leaves / of / Grass / complete / Autograph / & Portraits / 1882.” The endpapers, front and back, are a bright, glossy yellow. The title page presents the poem that begins, “Come, said my Soul, / Such verses for my Body let us write, (for we are one,)” printed just above Whitman’s signature. It carries the date, 1882, as that is the year it was printed, and the verso of the title page has an 1881 copyright notice. Two portraits of Whitman grace the book, the 1855 engraving of poet as a younger man (shown above) and, towards the back of the book, an image of an older Whitman (also shown above).

Our copy also is inscribed. On the front endpaper, in Whitman’s hand is written: John H. Johnston / from his friend / the author / Jan. 5 1885. Along with the donation of the book, we received a copy of the following obituary notice: “Johnston–On Monday, March 17, John Henry Johnston, in the 82nd year of his age. Funeral services at his late residence 389 Clinton St., Brooklyn. Wednesday March 19, at 2PM. Interment private.”

John Henry Johnston was born in 1837, died in 1919, and was Whitman’s friend and benefactor. Born in Sidney, NY, he came to New York in 1853, found employment in a Manhattan jewelry store and five years later became a partner and owner of the company. In 1873, Johnston purchased from his friend the 1860 portrait of Whitman painted by Charles Hine so that the poet would have enough money to move to Camden, NJ following the death of his mother. In following years, Whitman would often stay at the Johnston home on East Tenth Street when in New York. (The 1860 portrait, by the way, said to be Whitman’s favorite, was the source for the engraving of Whitman that is featured in the 1860 third edition of Leaves of Grass, also available in Special Collections.) In 1877, Johnston commissioned Elmira artist, George W. Waters to paint another portrait of Whitman.

In this 1882 Author’s edition, we have a fine, signed, presentation copy of a rare edition of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Come see it along with several other nineteenth and twentieth century editions at Special Collections.

Posted originally by marc9.

An Eighteenth Century Take on a Greek Classic

On my first day working at Virginia Tech Special Collections as a graduate student assistant, I was given a tour behind-the-scenes. As I walked through rows upon rows of the stacks where our rare books are housed, practicing hunting down books based on their call numbers, a large folio book stamped with Thucydidis Historiae on the spine immediately caught my eye. This book, published in 1731 in Amsterdam, presents book eight of Thucydidess history of the Peloponnesian Wars. In his account, the Greek historian Thucydides traces the buildup of hostilities between the city-states, Athens and Sparta, and narrates the battles and events that occurred throughout the course of the war. While I have encountered many other fascinating folios and tomes in our rare book collection, including other editions of Thucydides published in 1828, 1855, and 1950, this Thucydidis De Bello Peloponnesiaco libri octo remains my favorite.

Following a beautiful engraved frontispiece by J. C. Philips, the title page lists first the Greek title and then its longer explanatory Latin one.

My favorite part about this edition of Thucydides’s work is the frontispiece, depicting an eighteenth-century interpretation of a siege from classical antiquity. You certainly don’t need to be a Classics scholar to appreciate the fine detail and artistry. I notice something new every time that I look at this engraving.

Although not uncommon for this time period, the dedication and introduction are all written in Latin. Similar to today’s Loeb’s Classics, which provide English translations alongside the original Latin or Greek, this 1731 edition of Thucydides also supplied aid for translating the Greek… albeit in Latin.

All the accompanying notes and commentary are also in Latin. Since Thucydidess history of the Peloponnesian War was included within the traditional canon of classical texts that were instilled upon students in the academies in Europe and America during the eighteenth-century, perhaps it is not so strange to encounter Latin rather than English within this work.

We dont have a record here at Special Collections regarding this books exact history. To speculate, though, whoever owned or read this book was probably either educated or someone with status, and most likely both. However, when you visit Special Collections, you dont have to put on aristocratic airs or show off any classical knowledge to view and engage with our rare books like Thucydidis De Bello Peloponnesiaco libri octo.

Posted originally by vtspecblogger.

Not an Optick-al Illusion: Rare Isaac Newton Text at VT

In 2007, Special Collections at Virginia Tech was graciously gifted a copy of Isaac Newtons Opticks or a Treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and Colours of Light.

Opticks was Newton’s second major book on physical science and was first published in English in 1704, with a scholarly Latin translation following in 1706. The book analyzes the fundamental nature of light by means of the refraction of light with prisms and lenses, the diffraction of light by closely spaced sheets of glass, and the behavior of color mixtures with spectral lights or pigment powders.

The publication of Opticks represented a major contribution to science, and was well received and hotly debated upon its release. Opticks is largely a record of experiments and the deductions made from them, covering a wide range of topics. In the book Newton sets forth in full his experiments, first reported to the Royal Academy of London in 1672 on dispersion, or the separation of light into a spectrum of its component colors. He demonstrates how the appearance of color arises from selective absorption, reflection, or transmission of the various component parts of the incident light.

The major significance of Newton’s work is that it overturned the dogma, attributed to Aristotle or Theophrastus and accepted by scholars in Newton’s time, that “pure” light (such as the light attributed to the Sun) is fundamentally white or colorless, and is altered into color by mixture with darkness caused by interactions with matter. Newton showed just the opposite was true: light is composed of different spectral hues, and all colors, including white, are formed by various mixtures of these hues.

The copy belonging to Special Collections is a 3rd edition of the text, printed in 1721 in London for William and John Innys and was the last edition produced during Newtons lifetime. This nearly 300 year old leather bound book is in excellent condition, even the fold-out pages containing diagrams of Newtons experiments.

The gift was designated by the donors in honor of Matthew Charles Ziegler, Class of 2003. Since it is not recommended that modern materials such as bookplates and their glue be attached to such extraordinary and rare books, this information is noted in the bibliographic record. What a great way to commemorate a Hokie!

Posted originally by thompc.

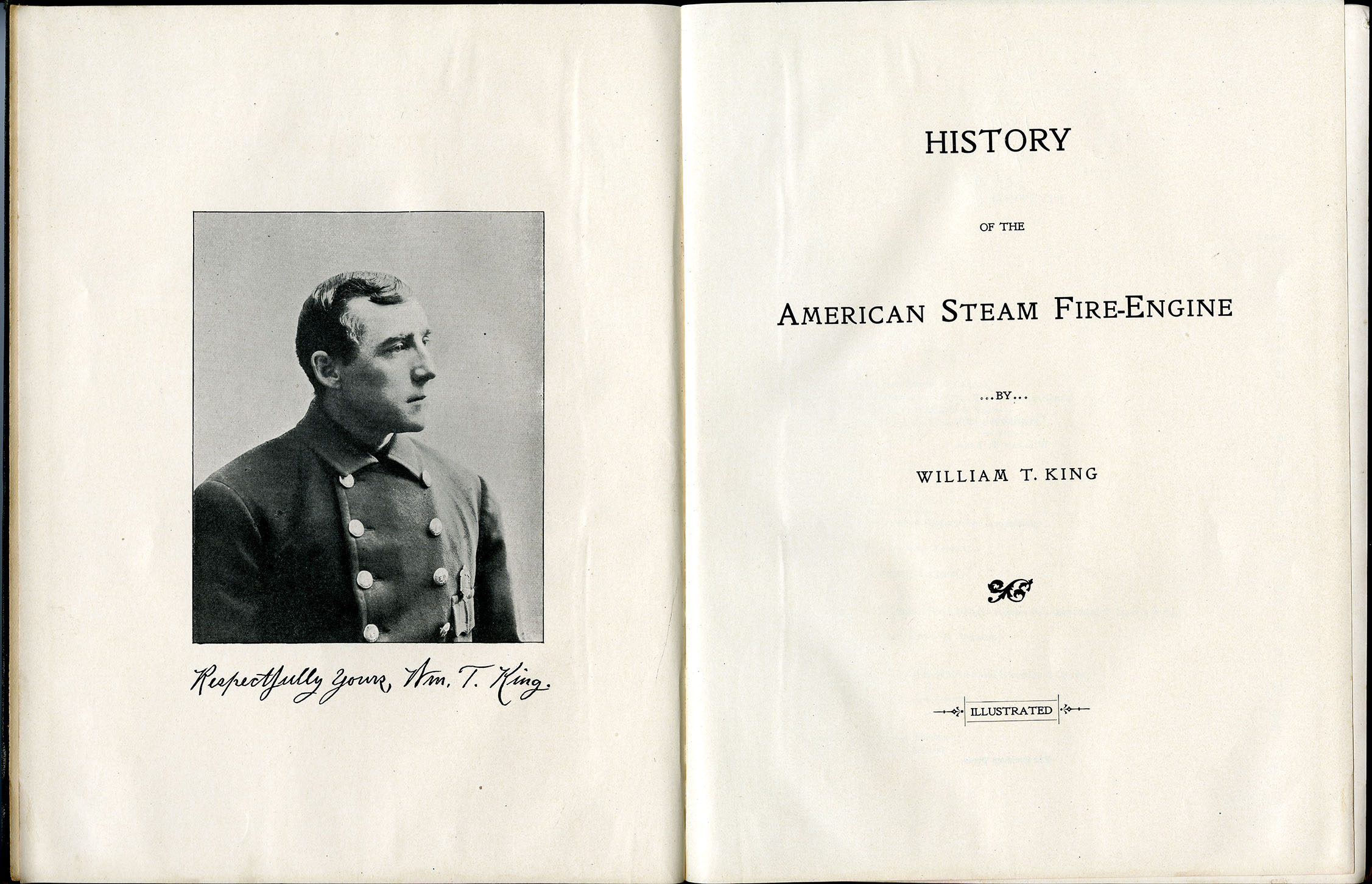

Everybody Likes Fire Engines . . . Don’t They. . . ?

Well, as long as they’re not having to put out a fire nearby.

But if you like fire engines, the 19th century, or just things mechanical, King’s book is for you. From the first steam fire engine, a British invention, the “Novelty,” built by George Braithwaite in 1829 to the “New American” engine of 1894, King will show you the machines, explain the detail and development of their inner workings, and describe the power of these rigs that made pumping water by hand to put out fires–at least in urban environments–a thing of the past.

As King writes:

“To England belongs the credit of conceiving the idea, and to America belongs the honor of perfecting the invention; and, as a result, the American steam fire-engine of to-day, in symmetry of parts, elegance of finish and efficiency of action stands unrivalled by any other in the world.”

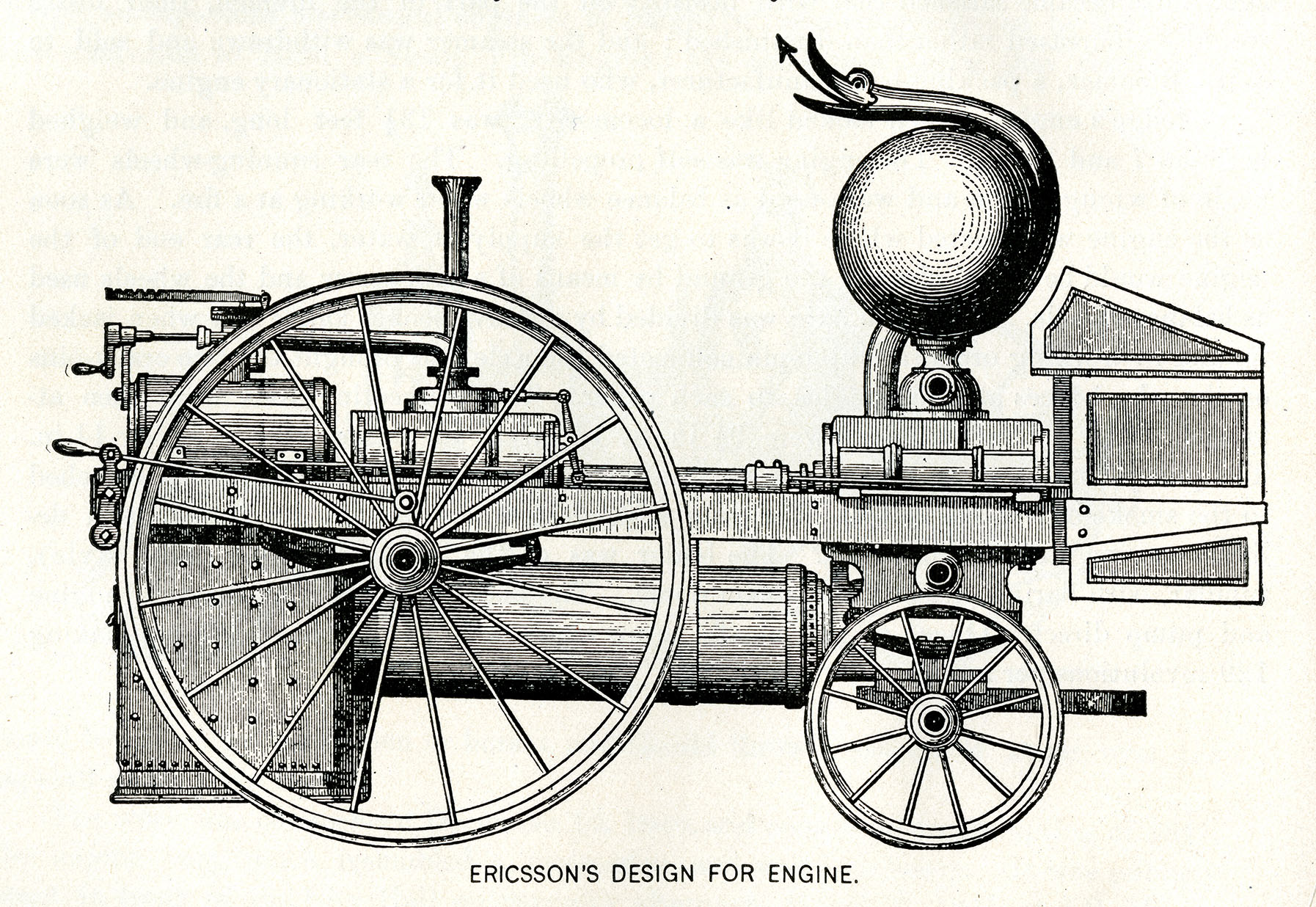

John Ericsson, later of Monitor (Civil war ironclad) fame assisted Braithwaite with his design. King offers a view a Ericsson’s own 1841 design for a steam fire engine, a device whose plans were submitted to the Mechanics’ Institute of New York, where it won the prize for the best design. Whereas the “Novelty” would throw 200 to 250 gallons of water per minute to a height of 90 feet, Ericsson’s own was designed to throw 3,000 gallons a minute to a height of 105 feet.

But Ericsson’s machine was never built. Still, King offers a description of Ericsson’s drawings and reproduces a sectional view of the engine.

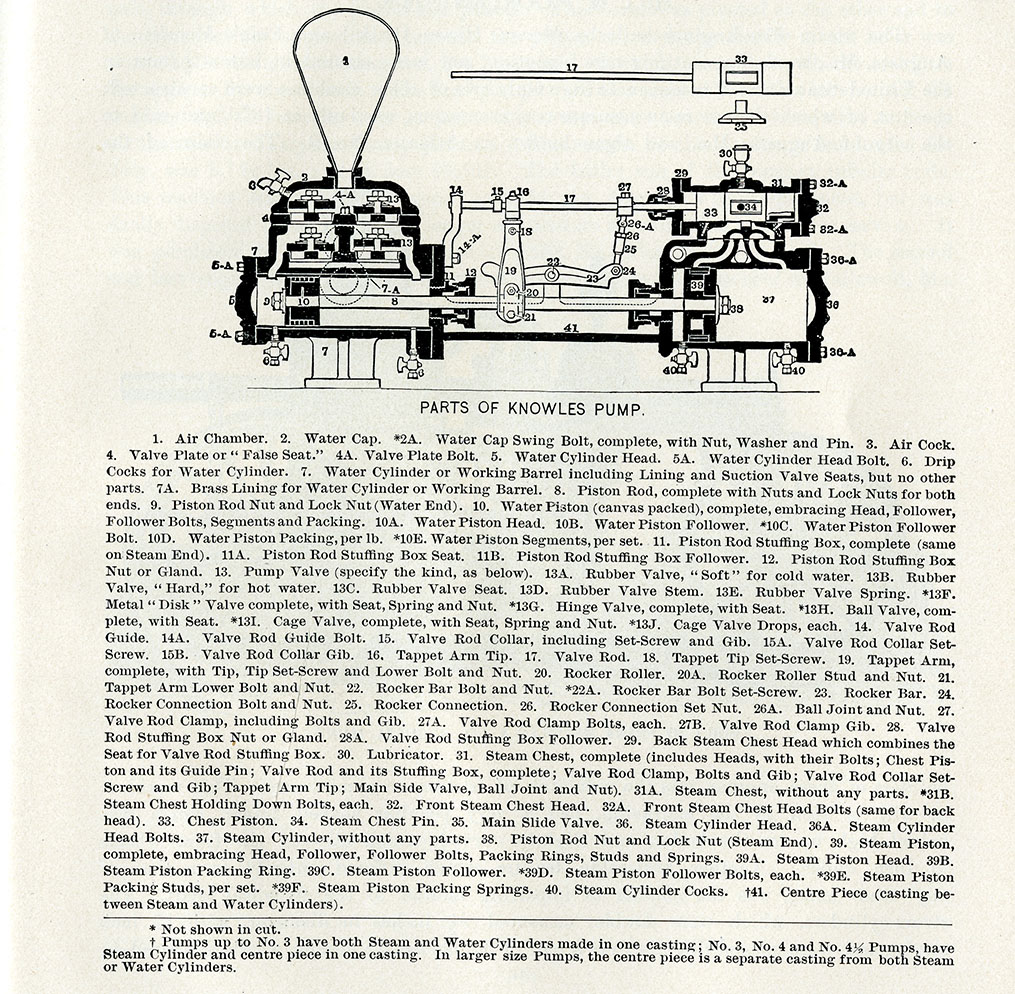

The combination of steam engine and pump demonstrated many forms, sizes, and capacities over the years. There were reciprocating piston pumps and rotary steam cylinders, vertical and horizontal boilers, 9,000 pound models and those weighing less than half that. First pulled by men, most were horse-drawn, a few were propelled by the steam engine onboard. A drawing of the pump used in the engine designed and built by the Knowles Steam Pump Works in 1875 shows just how complicated these machines could be.

William King’s Illustrated History will satisfy every curiosity about these machines. Here is a gallery of some of the other illustrations you will find in this book.

So, let’s thank Mr. King for writing his book and allowing us to see the wonderful variation of invention.

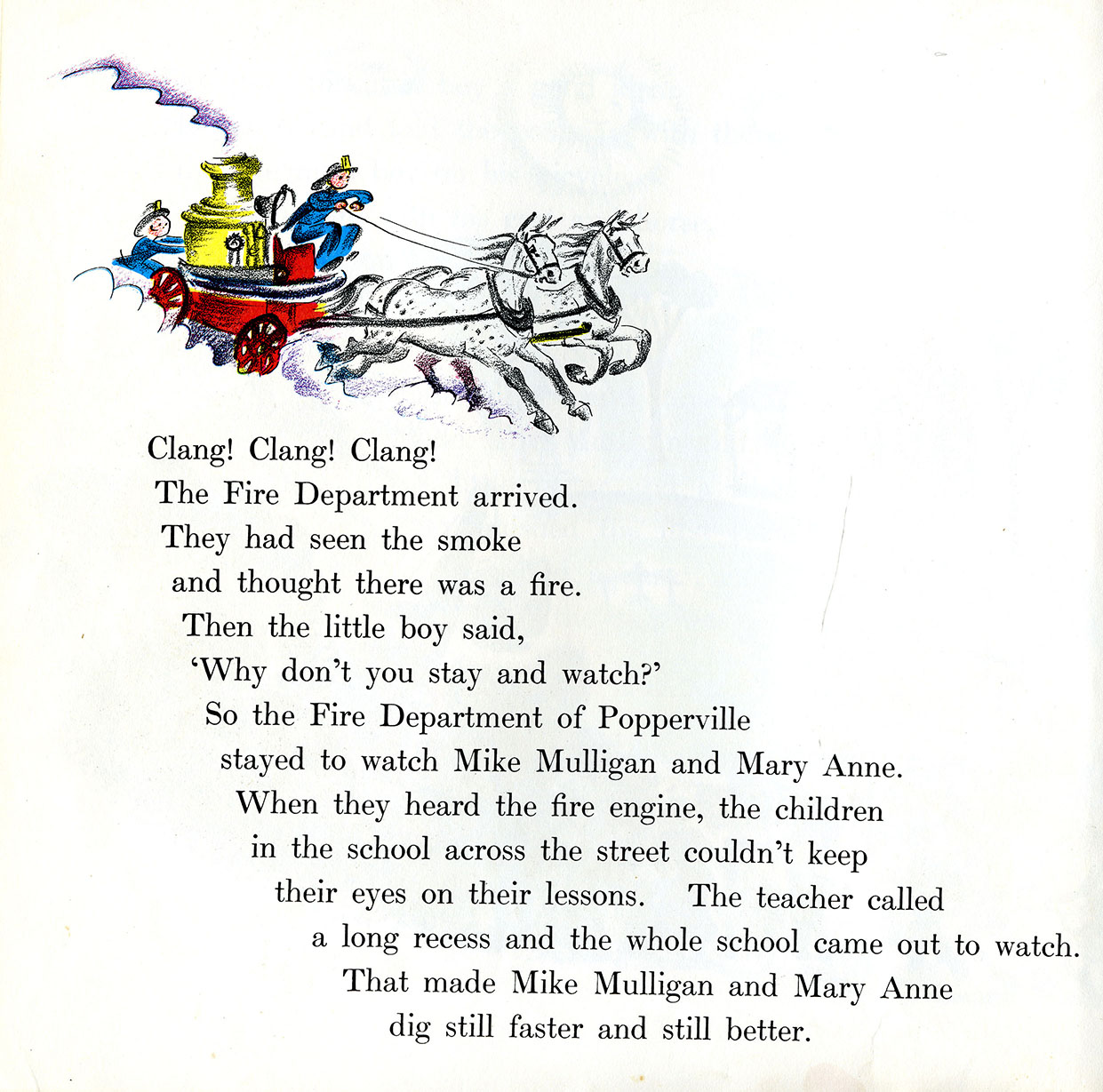

. . . and, of course, if reality isn’t quite enough, there is always the look and feel of fiction:

Come visit the steam fire engines of William T. King at Special Collections!

Posted originally by marc9.

Thomas Hobbes’s Homer

Thomas Hobbes’s first printed work, which appeared in 1629, was a translation from the Greek of History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides. Hobbes was already forty years old at the time, and it was the first English translation of this work directly from the Greek text. An earlier English version had been produced from a French translation of a Latin translation. In 1676, Hobbes returned to the work, preparing a corrected and amended second edition, while a third edition was published in London in 1723, forty-four years after Hobbess death. As Robin Sowerby wrote in 1998 of his Thucydides:

If the evidence of library catalogues can count for anything, this translation of Hobbes’ is probably one of the very few translations of a classical prose writer, perhaps the only one, that has to some extent survived the test of time that in the judgment of Longinus and of Dr. Johnson can alone convey classic status upon a literary work. At any rate, his translation is in itself a fine work of prose that deserves to be better known.1

Writing for the University of Chicago Press for an edition of David Grene’s edition of Hobbes’s Thucydides, Joseph Cropsey says:

Thomas Hobbes’s translation of Thucydides brings together the magisterial prose of one of the greatest writers of the English language and the depth of mind and experience of one of the greatest writers of history in any language. . . .2

Hobbes’s translations of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, completed in 1676, three years before he died at the age of 91 have been received somewhat differently. Beginning with Alexander Pope, whose own translations of Homer appeared between 1715 and 1720, Hobbes received rough treatment. From Pope’s preface to his edition of the Iliad:

Hobbes has given us a correct Explanation of the Sense in general; but for Particulars and Circumstances he continually lopps them, and often omits the most beautiful. As for its being esteemed a close Translation, I doubt not many have been led into that Error by the Shortness of it, which proceeds not from his following the Original Line by Line, but from the Contractions above mentioned. He sometimes omits whole Similes and Sentences; and is now and then guilty of Mistakes, into which no Writer of his Learning could have fallen into, but thro’ Carelessness. His poetry . . . is too mean for Criticism.

G. R. Riddehough, writing in Phoenix in 1958 goes on to say of Popes comment, “Severe as this censure may be, most people who examine Hobbes’ translations for themselves will agree that Pope could with justice have said yet harsher things.” Riddehough takes the opportunity in his article to do exactly that. He concludes his article with:

Writers on Hobbes have very little to say in defence of these Homeric renderings. If they mention the translations at all, it is usually to claim indulgence for the work of a very old man who wrote them for his own amusement, and it is scarcely likely that in the history of translations they will ever be promoted to a higher place. What value they possess is as a sidelight on the tastes and the classical scholarship of one of the leading philosophers of the Seventeenth Century.3

Hobbes’s own stated opinion, which appears towards the end of his Reader’s introduction to The Odyssey, seems to anticipate, if not encourage and agree with the criticism to come:

But howsoever I defend Homer, I aim not thereby at any reflection upon the following Translation. Why then did I write it? Because I had nothing else to do. Why publish it? Because I thought it might take off my Adversaries from showing their folly upon my more serious writings and set them upon my Verses to show their wisdom.4

Might Hobbes’s adversaries have nearly as much do to with his translations of Homer as with the controversial views expressed in his “more serious” political and religious work? Hobbes had made enemies on many fronts, particularly after the publication of Leviathan in 1651 (Yes, that Leviathan. You remember, Hobbes’s declaration of the state of nature giving rise to “the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”). But after the restoration of the British monarchy in 1660 his views, for example, on the role of religious doctrine in subverting political authority, continued to be problematic, if not dangerous. He was, for a time, concerned that he might be prosecuted for heresy. After 1662, with the passage of the Printing Act, which required that all books be licensed by church authorities prior to publication, Hobbes would, in fact, publish nothing in those fields in which his views had been seen as controversial: law, history, politics, or religion. Translations of classic works of Greek literature, however, may have provided an opening.

In 2008, Eric Nelson published the first modern critical edition of Hobbes’s translations of Homer. In his Introduction and notes, Nelson argues that these last major works of Hobbes are an attempt, via translation, to reinterpret Homer’s texts to support his own political philosophy, that “Hobbess Iliads and Odysses of Homer are a continuation of Leviathan by other means.”5 Nelson offers close readings of Hobbes’s translations to show how the very omissions, the rewriting of Homer for which Hobbes had been first castigated and then neglected over the centuries, can be understood as Hobbes’s attempt to use Homer as a cloak for the dissemination of his own views. Rather than a “sidelight on the tastes and the classical scholarship of one of the leading philosophers of the Seventeenth Century,” these translations may represent Hobbes’s views made public in the only way available to him at the time. The importance of the translations, as suggested by Dean Hammer in 2011, “rests in large part, then, on mistranslation.”6

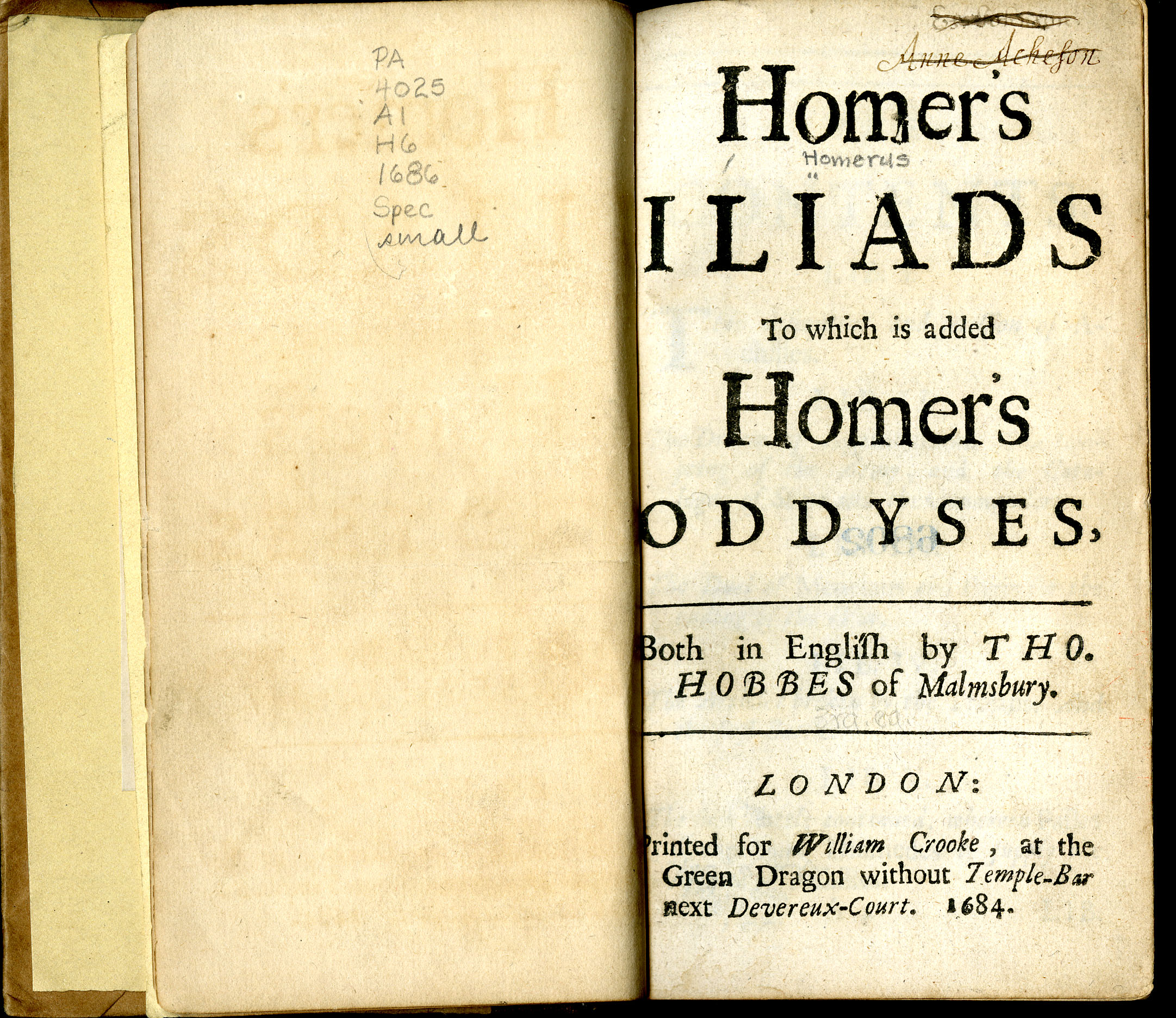

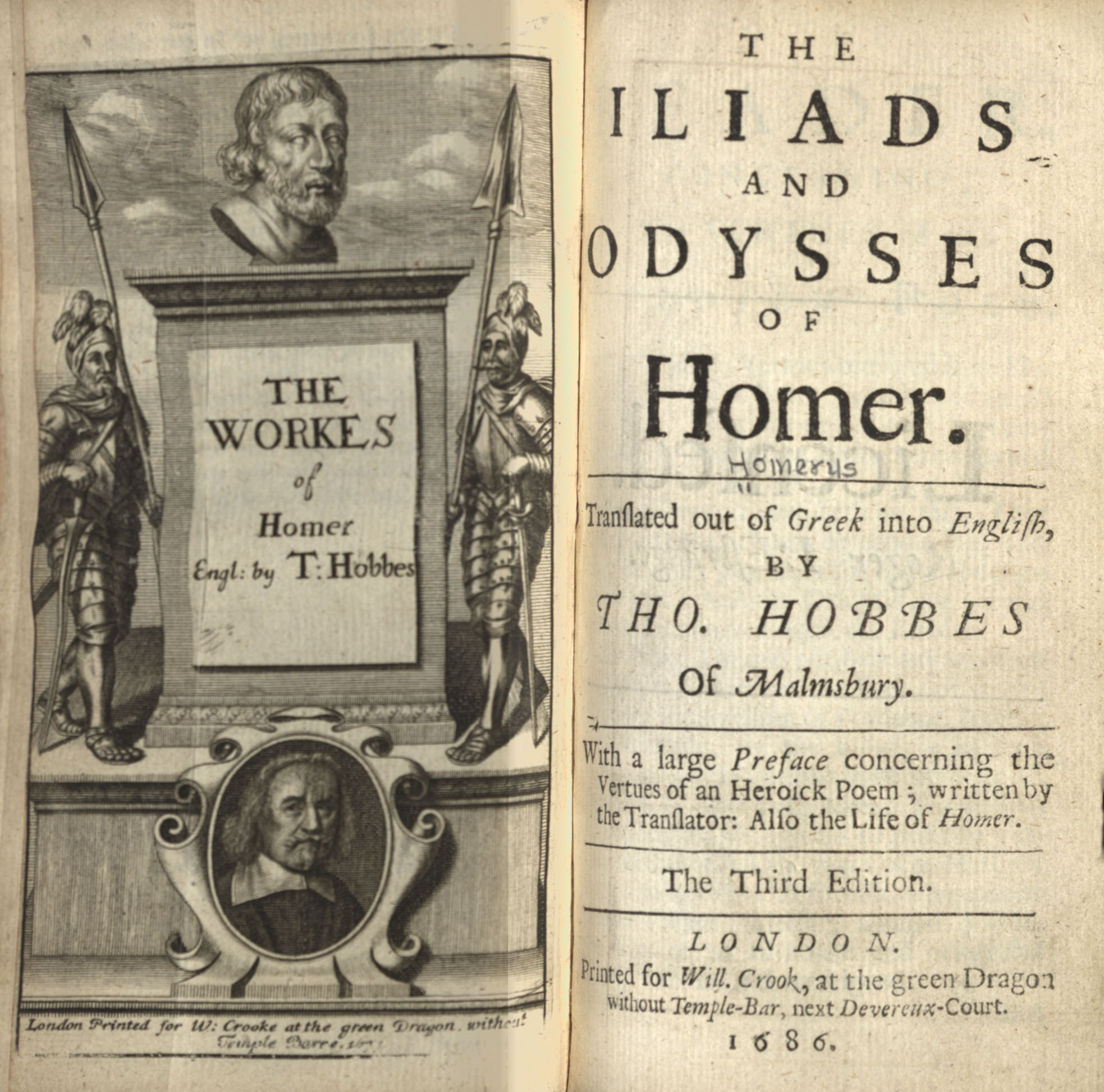

As for the copy in Special Collections, it is the third edition of Hobbes’s translation of Homer’s Odysses (1686), which was bound with the 1684 printing of his translation of Homer’s Iliads. The former includes “a large Preface concerning the Vertues of an Heroick Poem; written by the Translator: also The Life of Homer.” This copy has since been rebound. Both were printed “for William Crook, at the Green Dragon without Temple Bar next, Devereux-Court.”

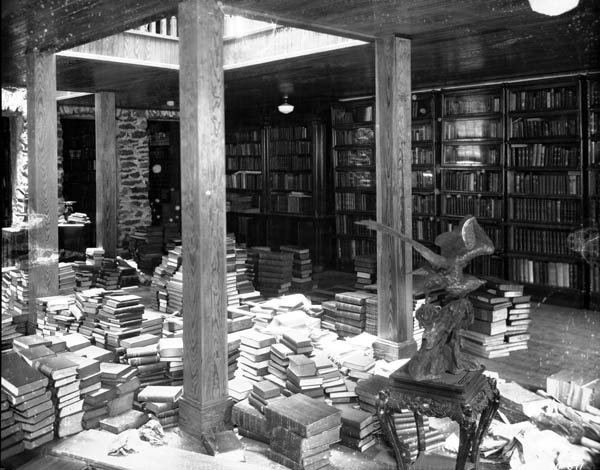

This particular copy belonged to Forster A. Sondley of Asheville, NC. An inscription consisting of his signature; the name of his home, Finis Viae (End of the Road); and the date, January 16, 1919 appears prior to the title page. Sondley was a lawyer, scholar, and bibliophile who accumulated a personal library of over 30,000 volumes. Upon his death in 1931, that library was bequeathed to the city of Asheville and formed the core of the Sondley Reference Library at Ashevilles Pack Library.

Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville NC, ca. 1950s

NOTES

1. Robin Sowerby, Thomas Hobbes’s Translation of Thucydides, Translation and Literature, Vol. 7, No. 2, 1998, p. 147.

2. Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War: The Complete Thomas Hobbes Translation with Notes and a New Introduction by David Grene, University of Chicago Press, 1959, 1989.

3. G. B. Riddehough “Thomas Hobbes’ Translations of Homer,” Phoenix, Vol. 12, No. 2, Summer, 1958, p. 62.

4. Thomas Hobbes, “To the Reader,” from, The Iliads and Odysses of Homer translated out of Greek into English by Tho. Hobbes of Malmsbury ; with a large Preface concerning the Vertues of an Heroick Poem; written by the translator, Third Edition, London, 1686.

5. Eric Nelson (ed.), Thomas Hobbes: Translations of Homer, (2 vols.), Oxford University Press, 2008, p. xxii.

6. Dean Hammer, “Translations of Homer, 2 vols, edited by Eric Nelson, Oxford University Press, 2008,” reviewed in Political Theory, 2011 39: 166.

Posted by marc9.

Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow was published 40 years ago today, 28 February 1973!

Who could possibly forget characters like Tyrone Slothrop, the Rocket Man, the Rocketenmensch himself, as he reacts in the most inopportune way to the passing of a V-2 overhead? Or, as he infiltrates the postwar Potsdam conference to retrieve the hash that Pig Bodine had stashed there some time before. And doesn’t the octopus attack Katje Borgesius only to have Slothrop save her . . . with a crab! Major Duane Marvey, The White Visitation, Tantivy Mucker-Maffick and Teddy Bloat, the casino Hermann Goering, the Schwarzhommando, and the songs, the rhymes, the limricks. . . ! And Imipolex G, that new plastic, a component in the rocket, the V-2, an “aromatic heterocyclic polymer” developed by Laszlo Jamf for I. G. Farben, the folks who also brought you Zyklon B, the poison gas used in concentrations camps. The polymer has remarkable properties, because, you know, “They could decide now what properties they wanted a molecule to have, and then go ahead and build it.”

“A screaming comes across the sky.”

Is it too much? Forty years later? Too much acid? Too little restraint? No? Let Pynchon’s Proverbs for Paranoids swing you back to reality as you contemplate reading or rereading this mighty novel. Perhaps, I’ll even take it on again. Here they are:

Proverbs for Paranoids:

1. You may never get to touch the Master, but you can tickle his creatures.

2. The innocence of the creatures is in inverse proportion to the immorality of the Master.

3. If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about answers.

4. You hide, they seek.

5. Paranoids are not paranoid because they’re paranoid, but because they keep putting themselves, fucking idiots, deliberately into paranoid situations.

Special Collections has among its book collection the first edition of Gravity’s Rainbow, published by Viking Press, 28 February 1973; as well as the first British edition, published by Jonathan Cape and the first Viking paperback, both also published in 1973.

Before there was the Force (as in, May it Be With You), there was The Counterforce!

Posted by marc9