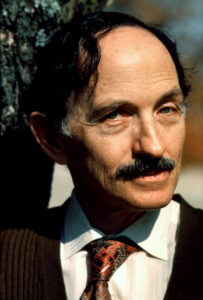

Enigma, Ultra, Alan Turing, Bletchley Park, the British efforts to break German codes in World War II. Maybe you’ve seen or are waiting to see the 2014 movie, The Imitation Game, which tells part of this story with Turing, quite rightly, as its central character. Perhaps you became aware of this highly classified historical episode when the secrecy surrounding it gave way to public sensation in the early 1970s, almost thirty years after the end of the war . . . or in the many books and movies that have followed. An interest in wartime history, cryptography, or the early development of computers provide only a few of the possible avenues into the story. But did you know that one of the primary characters in that story, a mathematician who earned a Ph.D from Cambridge in 1941 with a paper on topological dimension, was a professor of statistics at Virginia Tech from 1967 until his retirement in 1994, and lived in Blacksburg until his death just a few years ago at the age of 92? Maybe you did, but I didn’t. His name was I. J. Good, known as Jack.

He was born Isidore Jacob Gudak in London in 1916, the son of Polish and Russian Jewish immigrants. Later changing his name to Irving John Good, he was a mathematical prodigy and a chess player of note. In a interview published in the January 1979 issue of Omni, Good says of the claim that he rediscovered irrational numbers at age 9 and mathematical induction and integration at 13, “I cannot prove either of these statements, but they are true.”

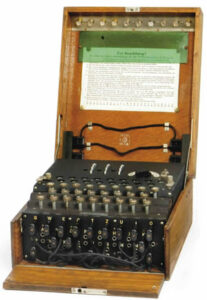

In 1941, Good joined the code-breakers at Bletchley Park, specifically, to work on the German Naval Enigma code in Hut 8 under the direction of Alan Turing and Hugh Alexander, the mathematician and chess champion who had recruited him. This is the story that is told in The Imitation Game, in which Jack Good is played by actor James Northcote. Along with Turing’s story, it is the story of the development of the machines that would break the German Enigma codes. The Enigma machine was an electromechanical device that would allow the substitution of letters–and thus production of a coded message–through the use of three (later four) rotors that would accomplish the substitutions. If you knew which rotors were being used and their settings, (changed every day or every second day), one could decode a message sent from another Enigma. If you didn’t know the rotors and the settings, as James Barrat writes in Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era, “For an alphabet of twenty-six letters, 403,291,461,126,605,635,584,000,000 such substitutions were possible.”

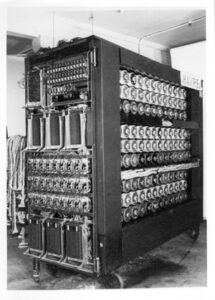

This is the world Jack Good entered on 27 May 1941, that and the world of war and the urgent need to defeat the Axis. Turing had already built some of the first Bombes, electromechanical machines–among the earliest computers, really–and had achieved initial and significant success. Good belonged to a team that would make improvements to the process from an approach based in a Bayesian statistical method that Good described in 1998 speech as “invented mainly by Turing.” He also called it “the first example of sequential analysis, at least the first notable example.” For the duration of the war, Good would work to further the British code-breaking technologies, adding his knowledge and understanding of statistics to the development of machines known as the “Robinsons” and “Colossus.” The program was remarkably successful. In its early days, it is credited with helping in the effort to sink the German battleship Bismarck; then helping to win the Battle of the Atlantic, directing the disruption of German supply lines to North Africa, and having an impact on the invasion of Europe in June 1944. What came to be known as “Ultra,” the intelligence obtained by the work of the Bletchley Park code-breakers, is, generally, thought to have shortened the war by two to four years. Jack Good, who worked with Alan Turing both during and after the war, said, “I won’t say that what Turing did made us win the war, but I daresay we might have lost it without him.”

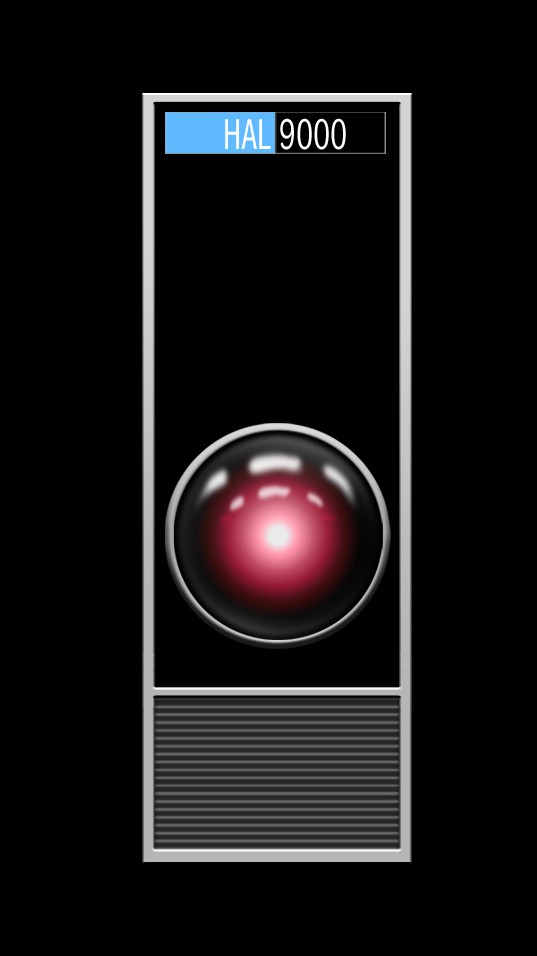

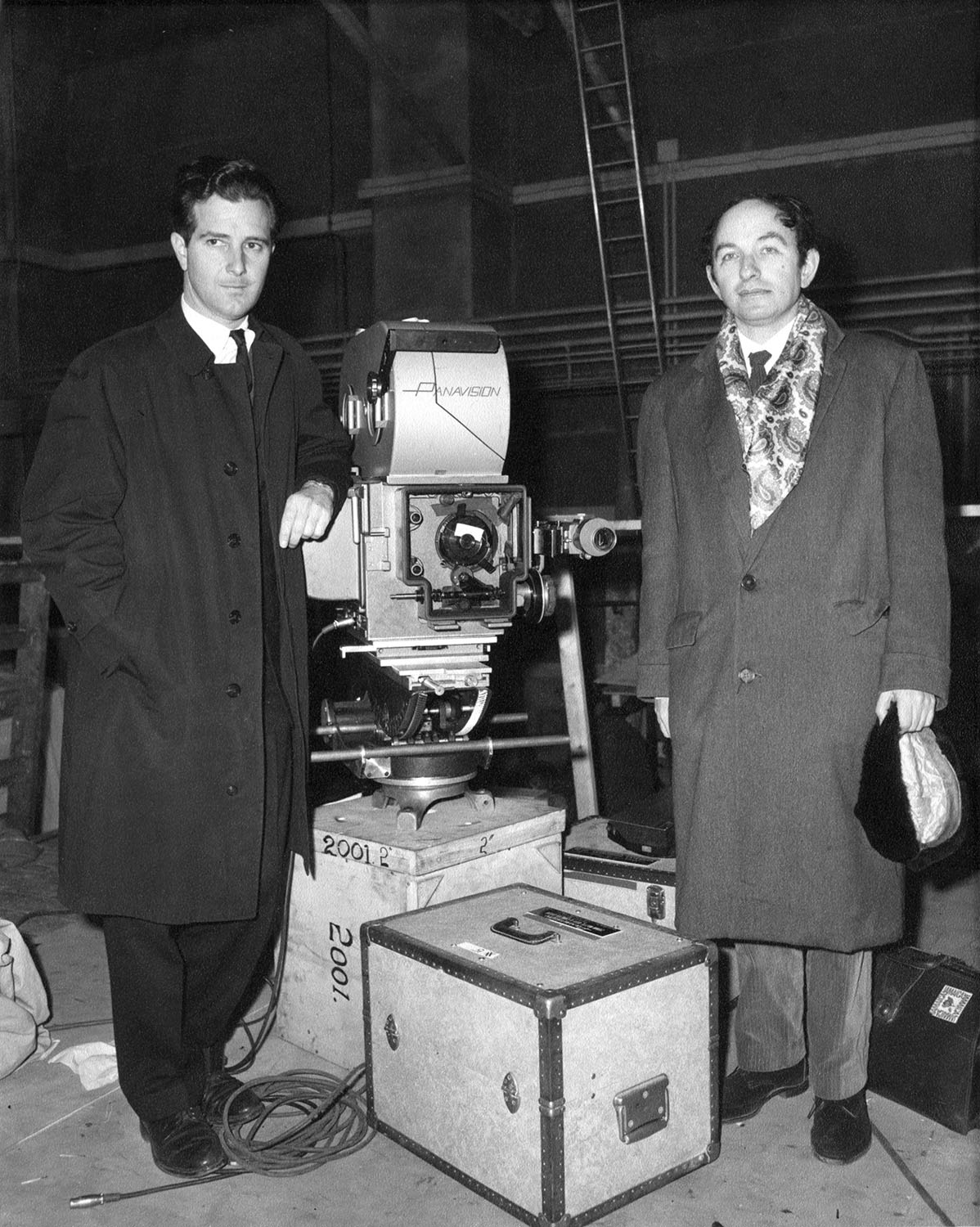

After the war, Good was asked by Max Newman, a mathematician and another Bletchley Park alum, to join him at Manchester University, where they, later joined by Turing, worked to create the first computer to run on an internally stored program. A few years later, he returned to Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) for another decade of classified work for the British government. A three-year stint teaching at Oxford led to a decision in 1967 to move to the United States, but not before he served as a consultant to Stanley Kubrick, who was then making 2001: A Space Odyssey. The HAL (Heuristically-programmed ALgorithmic computer) 9000–the computer with a mind of its own–presumably owed much to the mind of Jack Good.

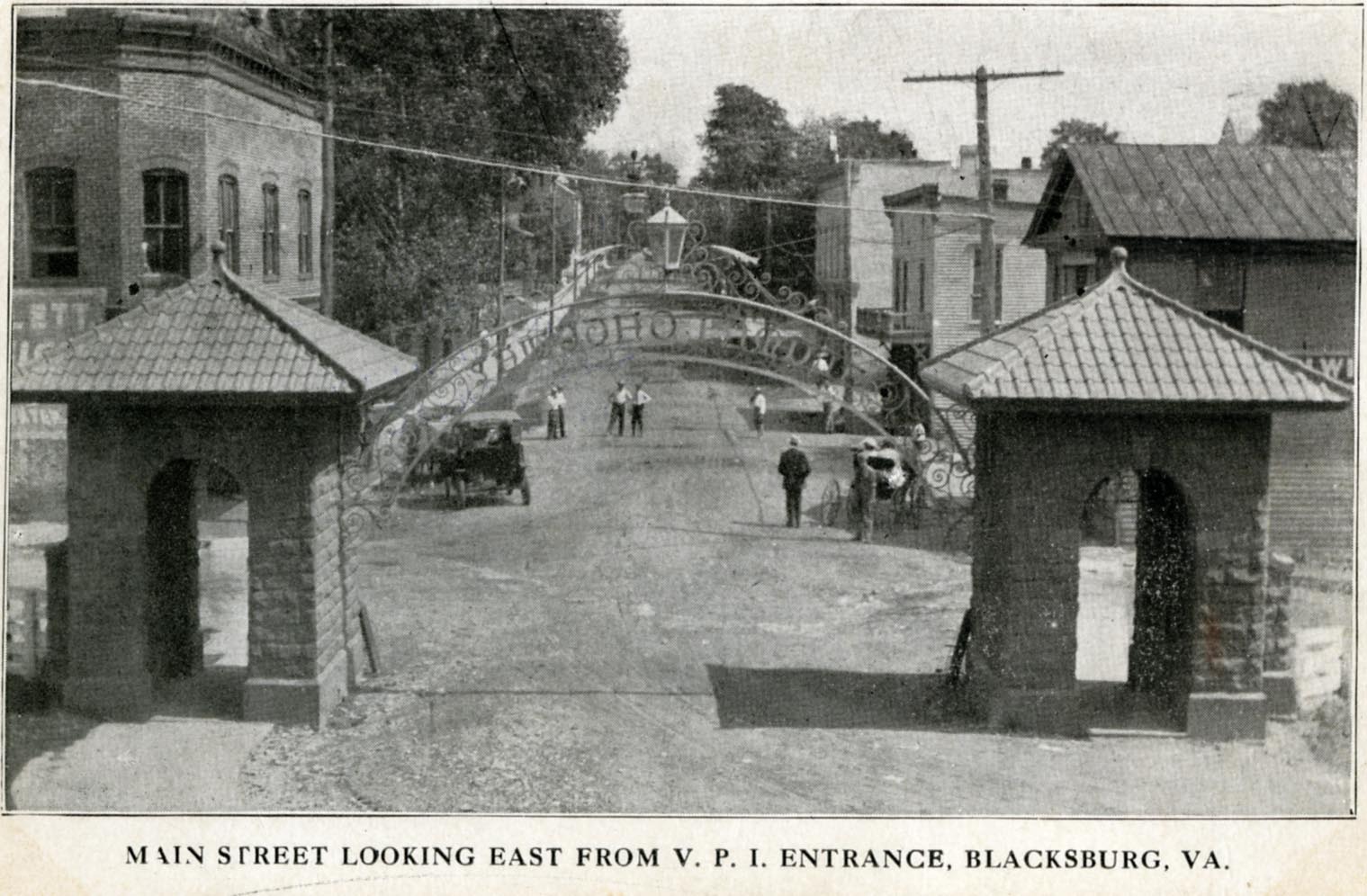

At Virginia Tech, Good arrived as a professor of statistics. Always a fellow for numbers, he noted:

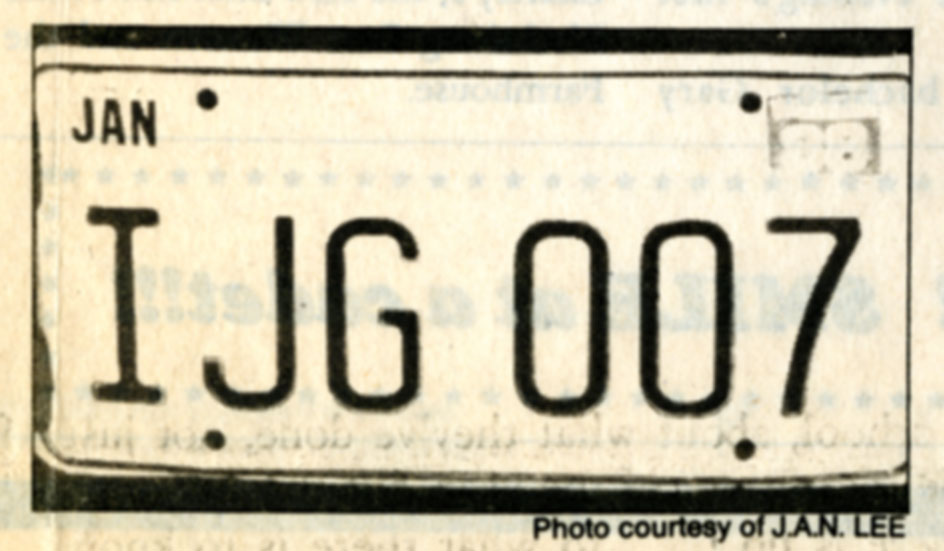

I arrived in Blacksburg in the seventh hour of the seventh day of the seventh month of year seven of the seventh decade, and I was put in apartment seven of block seven of Terrace View Apartments, all by chance.

Later, he would be University Distinguished Professor and, in 1994, Professor Emeritus. In 1998, he received the Computer Pioneer Award given by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Computer Society, one of a long list of honors. Good’s published work spanned statistics, computation, number theory, physics, mathematics and philosophy. A 1979 Omni article and interview reports that two years earlier a list of his published papers, articles, books, and reviews numbered over 1000. In June 2003, his list of “shorter publications” alone included 2278 items. He published influential books on probability and Bayesian method.

In that Omni interview, the conversation ranges over such topics as scientific speculation, precognition, human psychology, chess-playing computers, climate control, extraterrestrials, and more before settling in on the consequence of intelligent and ultraintelligent machines. On the latter topic, in 1965, Good wrote:

Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an “intelligence explosion,” and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.”

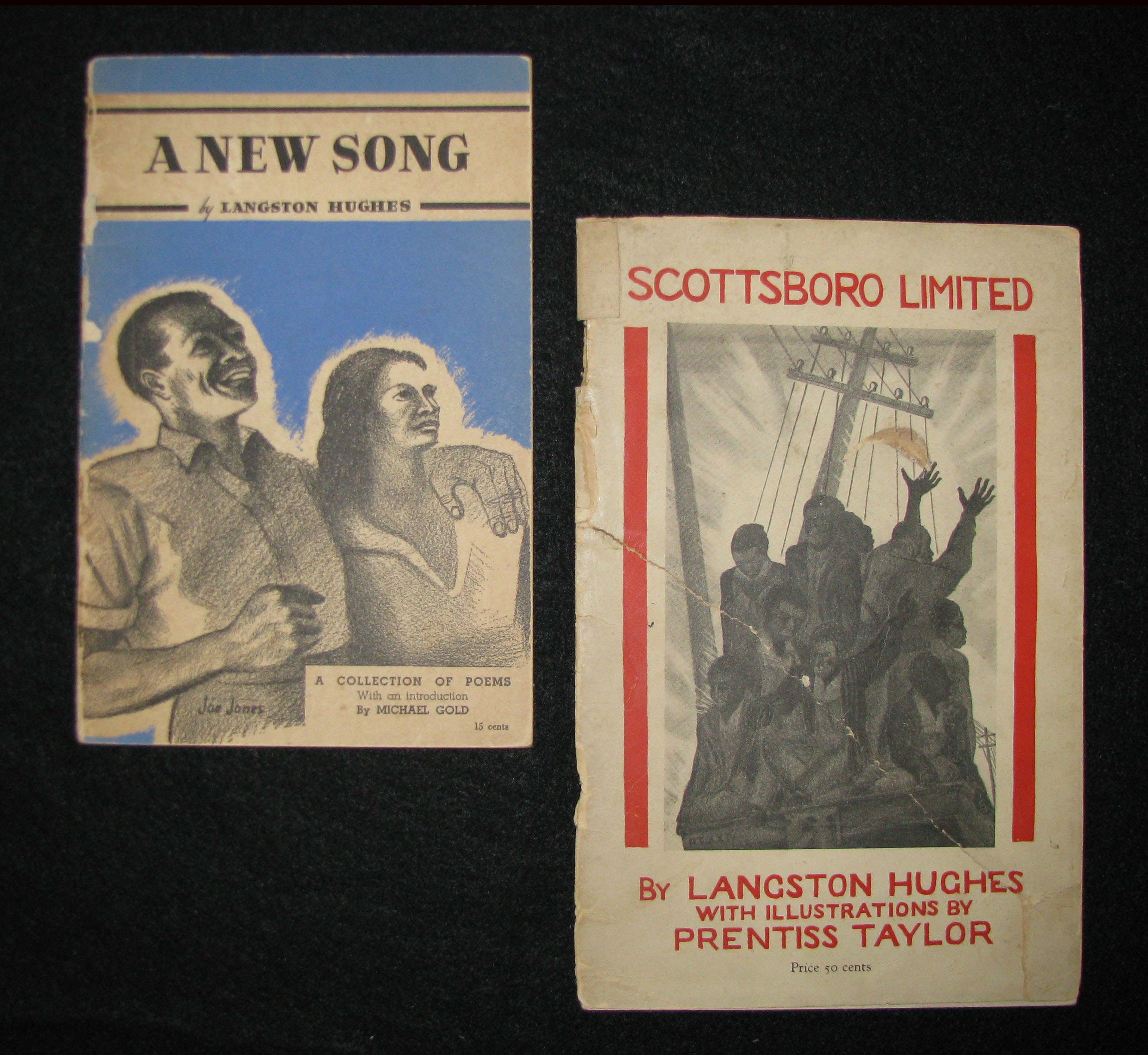

Special Collections at Virginia Tech has a collection of the papers of Irving J. Good that includes 36 volumes of bound articles, reviews, etc. along with a videotape of him and Donald Michie that commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of the work they both did at Bletchley Park. Among the rest of the material is some correspondence and a group of papers described as “PBIs,” which I now know to be “partly baked ideas,” some his own, many sent to him by others, but for which he appears to have had a fondness.

In the end, however, and as his 2009 obituaries suggest, it will be his code-breaking and other intelligence work, particularly from the days at Bletchley Park that I. J. Good will be most remembered. Even though he and all the participants were prevented from talking about that work for years, one guesses that Jack Good wanted to leave others with a sense of it, particularly once in Virginia, as he drove away, with his customized license plate: