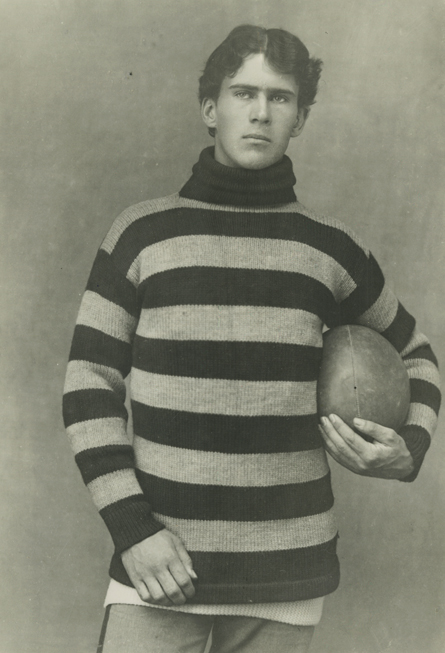

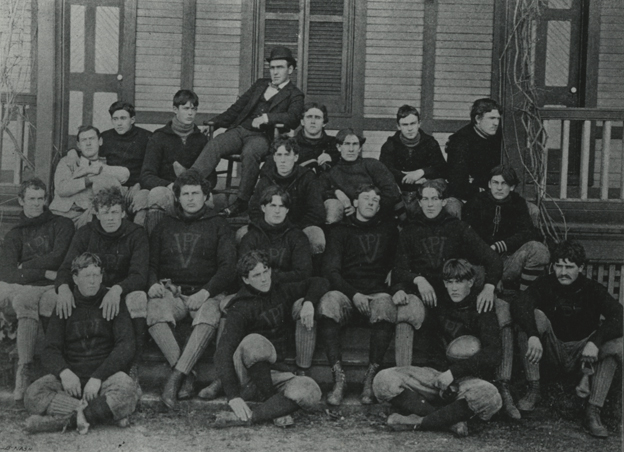

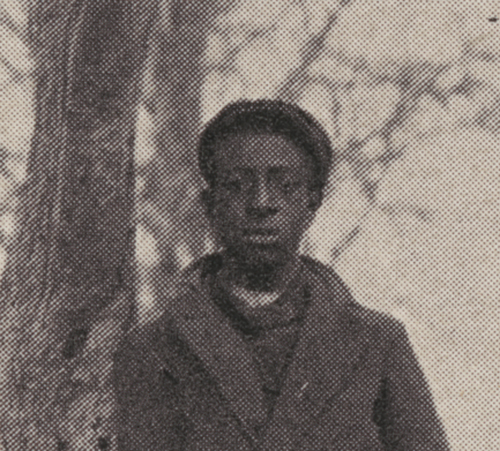

A century ago, the most recognizable face on Virginia Techs campus probably wasnt that of the college president (Joseph Eggleston) or the football coach (Charles Bernier) but instead belonged to a beloved figure now all but forgotten in campus lore, William Grove Uncle Bill Gitt, Virginia Techs original campus character.

Born to William and Amanda Gitt in Montgomery County, Virginia, in 1860, Gitt soon afterward moved with his parents to Newport, in neighboring Giles County. There, the Gitts operated the Gitt House, an inn that became a popular stop for cadets, especially during outings to nearby Mountain Lake.

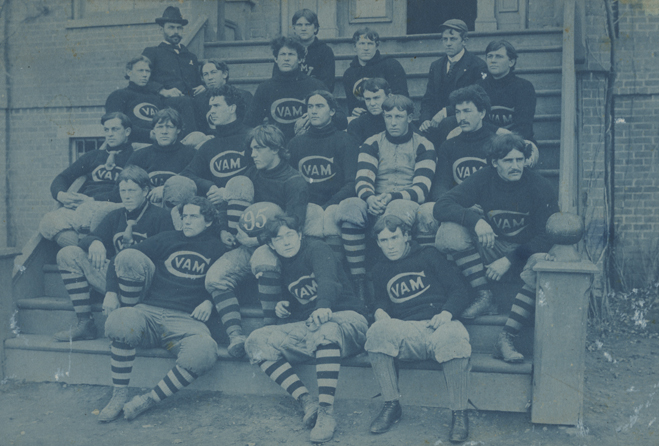

According to biographical information appearing in the 1918 Bugle and Col. Harry Temples The Bugles Echo, Gitt enrolled in what was then Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College in 1877. Having failed every subject during his freshman year at VAMC, Gitt began searching for employment. He somehow alit in New Haven, Connecticut, where he clerked in a 99-cent store for about a year before joining the Barnum & Bailey Greatest Show on Earth as a circus clown. After a single season, Gitt left the circus and worked successively as a brakeman, fireman, and conductor on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, but he returned to performing for Barnum & Bailey three years later. He remained with the circus for several seasons, including a European tour, but an injury in 1891 forced his retirement from performing. After retiring from the circus, Gitt worked at several jobs in Chicago, where he is said to have saved the lives of two children. He was later employed as a railroad brakeman for four years, then as a bartender in Huntington, West Virginia, for another four years.

In 1907, Gitt returned to Blacksburg, where he operated a street corner stand, selling fruit, candy, and knickknacks. He soon became a favorite local figure of Virginia Techs cadets, who probably enjoyed the many stories he undoubtedly shared of his life and travels. Fond of composing bits of doggerel for every occasion, Gitt always ending his poems with Uncle BillThats all, and it was by this stock phrase that the cadets invariably referred to him.

In a move that was mutually beneficial, the university allowed the perpetually down-on-his-luck Gitt to move into Room 102 of Virginia Techs Barracks No. 1 (now known as Lane Hall) in 1911. In exchange for his room and a salary of $7.50 per month, Gitt performed various tasks for the cadets, as summarized in The Bugles Echo:

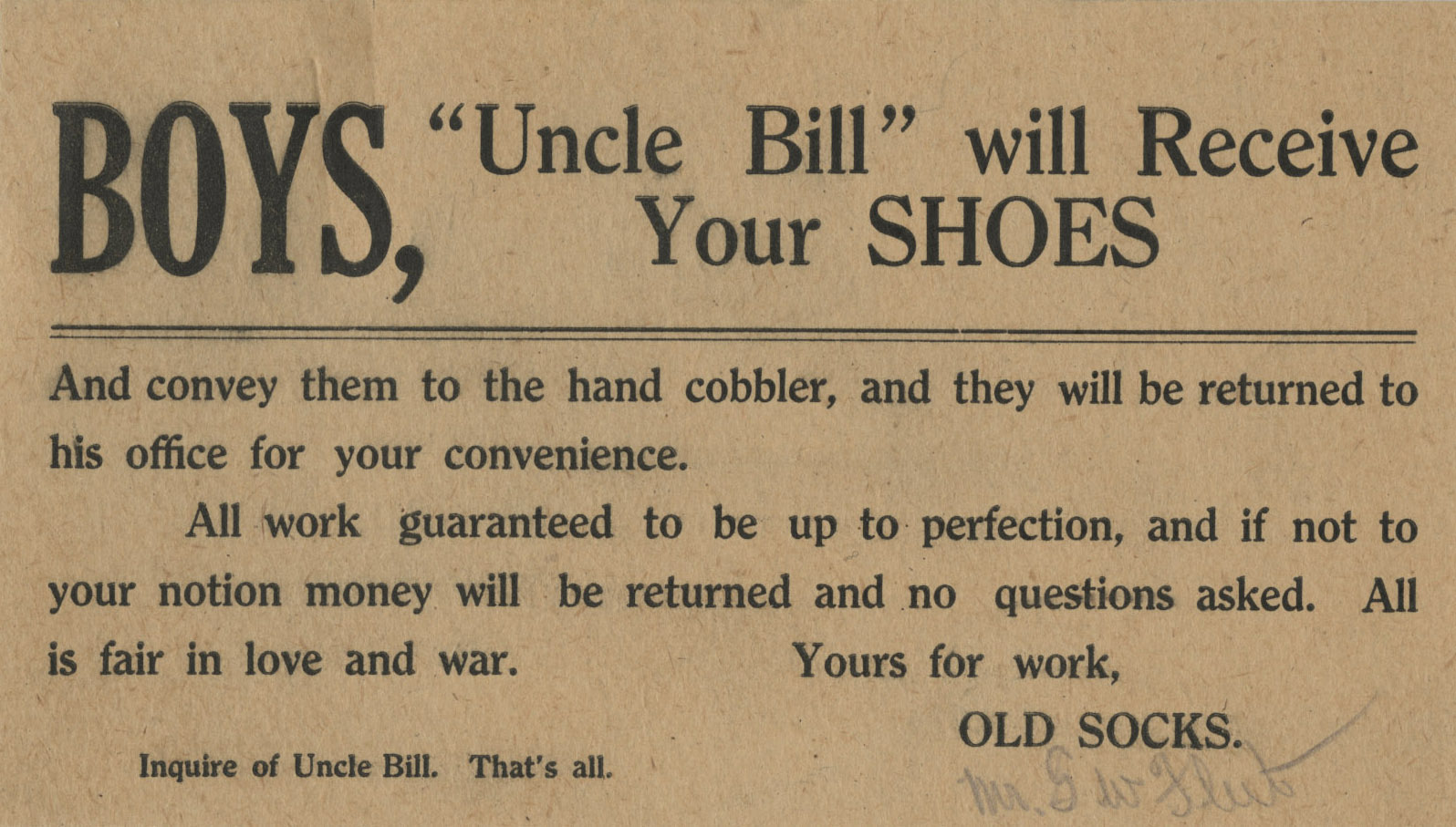

He handled incoming and outgoing express packages. The cadets left their bags of soiled laundry in front of his room, and he looked after them. He mailed letters, sold stamps, and ran errands such as buying cigarettes. He sold smoking equipment such as pipes and matches, and sold apples and notions, tickets for athletic events, Lyceum shows, and the Pressing Club. He operated a telephone service, relayed messages, and went to cadets rooms to call them to the telephone. He collected items for charities and acted as a coordinator between the boys and community projects and actions. He cashed checks at the downtown bank for the cadets and operated a lost and found service. He maintained a bulletin board in the hall outside of his room on which items of current interest were posted, including intercollegiate athletic scores.

Finding his salary to be insufficient, Gitt subsisted on gratuities as well as commissions on the sales of event tickets and fees for other odd jobs. Fortunately for him, faculty members frequently invited him into their homes for dinner.

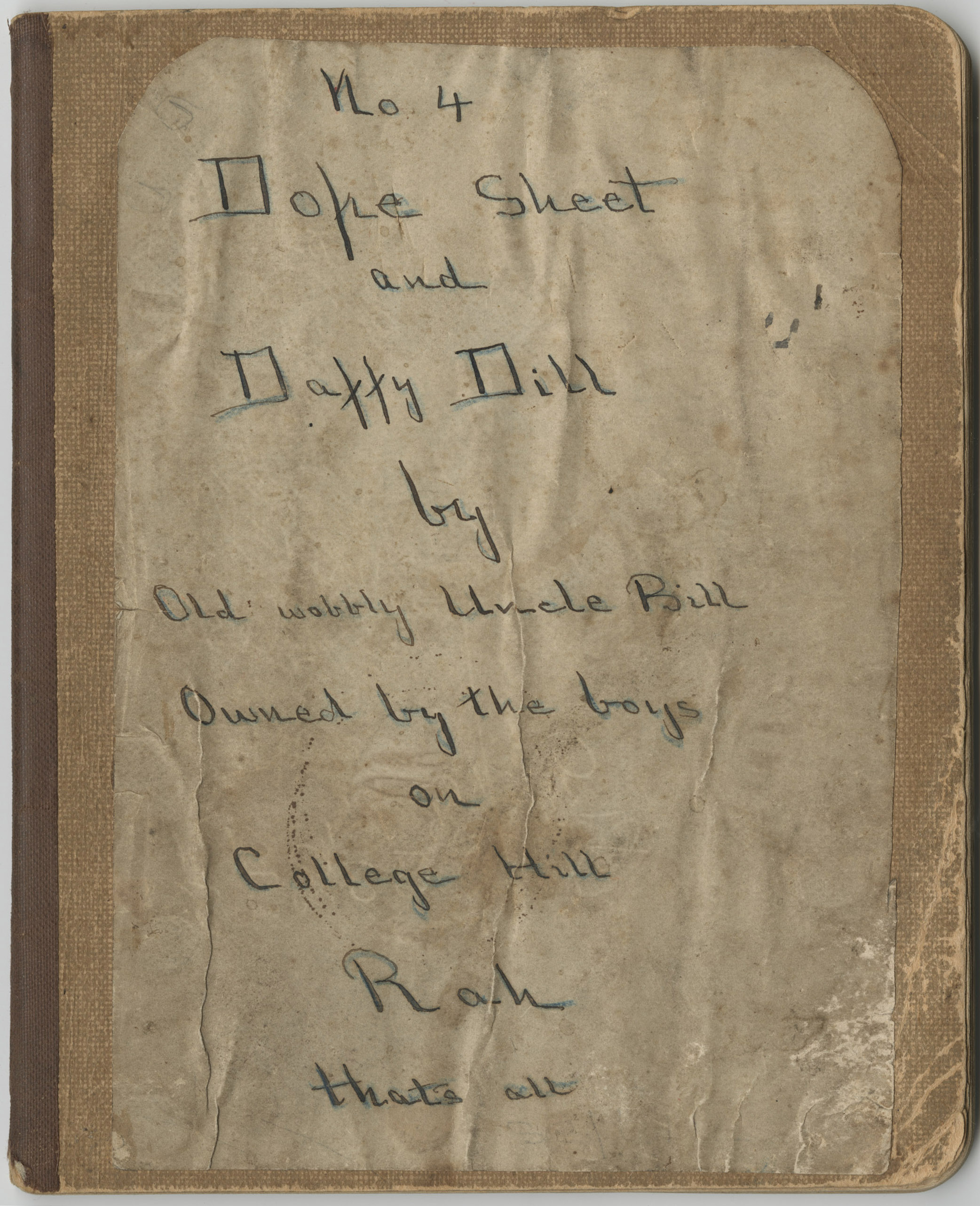

Here in Special Collections, were fortunate to have a journal maintained by Bill Gitt (Ms1964-006). Covering a period of 10 weeks in the fall of 1912, the journal is titled Dope Sheet and Daffy Dill. Always given to rhyme, Gitt couldnt help but refer to himself as Old wobbly Uncle Bill / owned by the boys on College Hill / Rah / Thats all.

In addition to describing his daily work and activities, Gitts journal chronicles his health problems and his dire financial condition. Throughout all, however, he tries to maintain a positive attitude, and the entries are full of slang and poetry. On November 28, 1912, he wrote: I am thankful that I am as well situated as I am. I have a good warm room, electric light, and plenty to eat, and clothes and shows. And the boys are my friends. I would not get by on $7.50 a month, if it was not for the boys.

Elsewhere, Gitt chronicles life among the cadets, mentioning fights, celebrations, and football games. He makes frequent mention of his roommate, Rusty the dog, who served as a college mascot, and of the cadets, invariably referring to them as my boys and with genuine affection.

By 1918, Gitts health had deteriorated to the point that he could no longer tend to his demanding duties at Virginia Tech. After Gitt underwent a surgical operation in Roanoke, an alumnus obtained for him a job in that citys Travelers Hotel. Medical bills soon eroded his savings, however, and Gitt had to move into the Roanoke City Almshouse, the last refuge for the areas indigent and aged in the days before government assistance.

Bill Gitt remained a beloved figure to students and alumni. Following his move to Roanoke, the cadets pooled their money and purchased for him a phonograph and a collection of his favorite records. They were sent to Gitt in Roanoke, accompanied by a letter of appreciation signed by every cadet. Each year, he received a complimentary subscription to The Virginia Tech (todays Collegiate Times). Despite his difficulties, Gitt revisited campus on several occasions and attended the annual Thanksgiving Day game between VPI and VMI until he died.

One cadets feelings about Virginia Techs first campus character were recorded in a 1917 Roanoke World News article:

Every one that knows Virginia Tech is sure to know Uncle William, for he is truly a part of the College. At any rate, the boys are very fond of the old man; and if any one would like to hear some real interesting experiences, just have a chat with Uncle BillThats All.