The New Student Experience, 1872-1902

As with any college town, August brings to Blacksburg a sudden shift from near-dormancy to feverish activity. Streets clog. Parking spaces disappear. And piles of modern lifes necessitiesfrom box fans to microwave ovens, from flat-screen TVs to mini-fridgesalign sidewalks as families and volunteers move new students into their appointed dorm rooms.

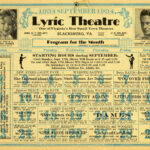

In the early years of Virginia Techthen known as Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical Collegestudent move-ins were much different. In 1872, the schools inaugural year, the new, non-local student arrived by train unaccompanied, alighting at the station near Christiansburg. The additional eight-mile journey by hired carriage to Blacksburg could take as long as three hours on roads that were sometimes nearly impassable. It wouldnt be until 1904 that a spur linethe Huckleberry Railroadwould allow for a much easier (though, at a scheduled 40 minutes, still-lethargic) trip from Christiansburg.

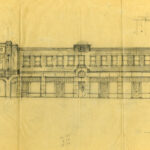

Upon arriving, the more sophisticated freshmen were probably unimpressed by their new surroundings. Blacksburg was barely a spot on the map at the time and couldnt provide much comfort and entertainment to young men far from home. The campus itself consisted of but five acres and a single building. Though it rose above the surrounding countryside, the three-story edifice was less than grand. Samuel Withers, who entered the school in early 1873, uncharitably wrote, The architect who planned it must have been a genius, for it was a classic in its ugliness.

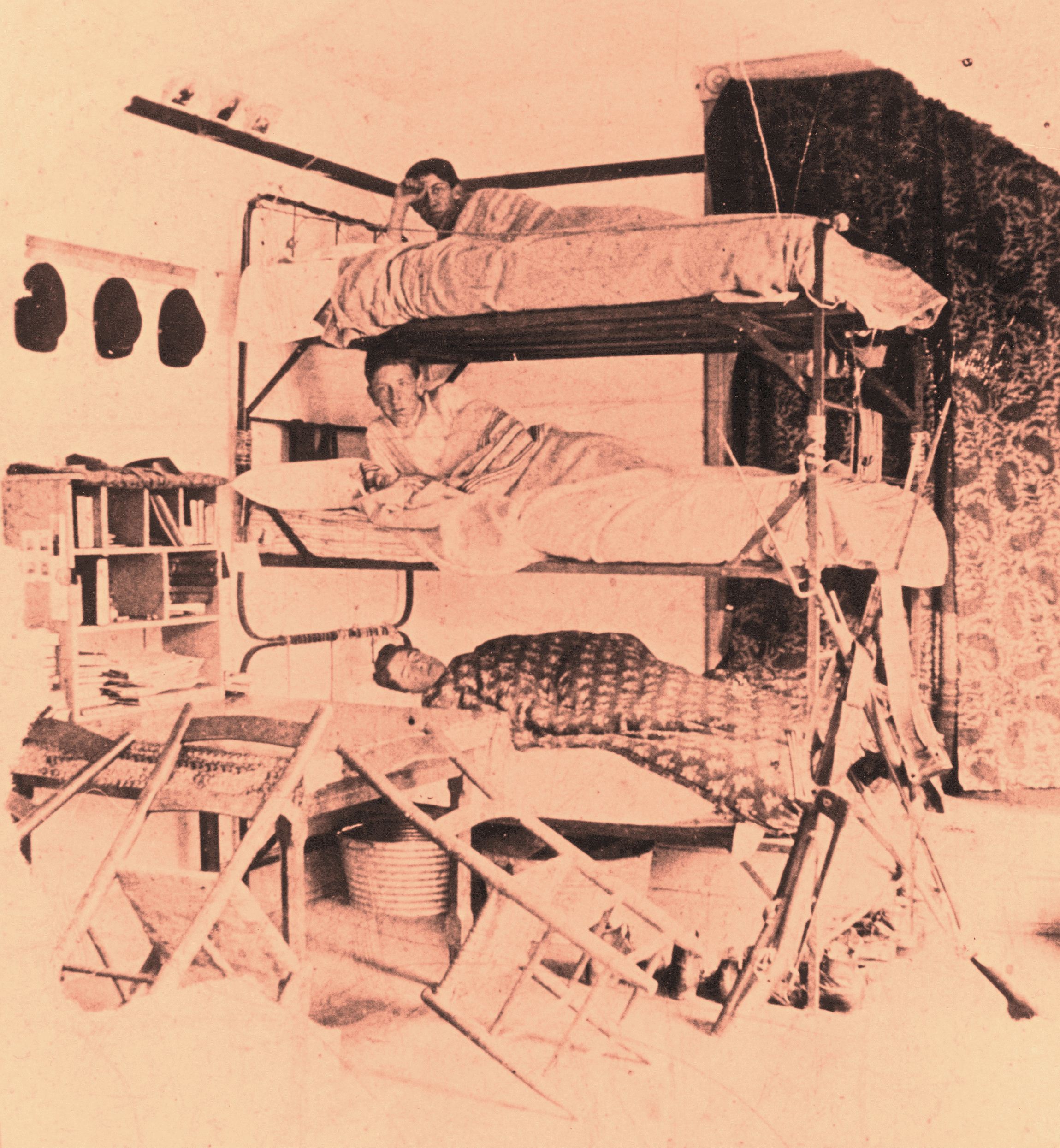

The building contained only 24 lodging rooms, which made for cramped quarters. Even after packing three cadets to a room, fewer than half of the first years 172 students could be accommodated.

As sometimes still happens today, with enrollment exceeding available rooms, students had to find alternative, off-campus lodging. Many acquired room and board in private homes. Others took up residence in structures hastily built by local entrepreneurs who saw in student rentals a potential windfall. One such building, at the corner of Church and Roanoke streets, was officially named Lybrook Row. The building apparently gained a somewhat notorious reputation, however, and was more familiarly known to cadets as Buzzards Roost and Hell Row. Still, these first-year cadets of what was then an all-male military school could take some comfort in living off-campus, where they were less subject to the control of upperclassmen.

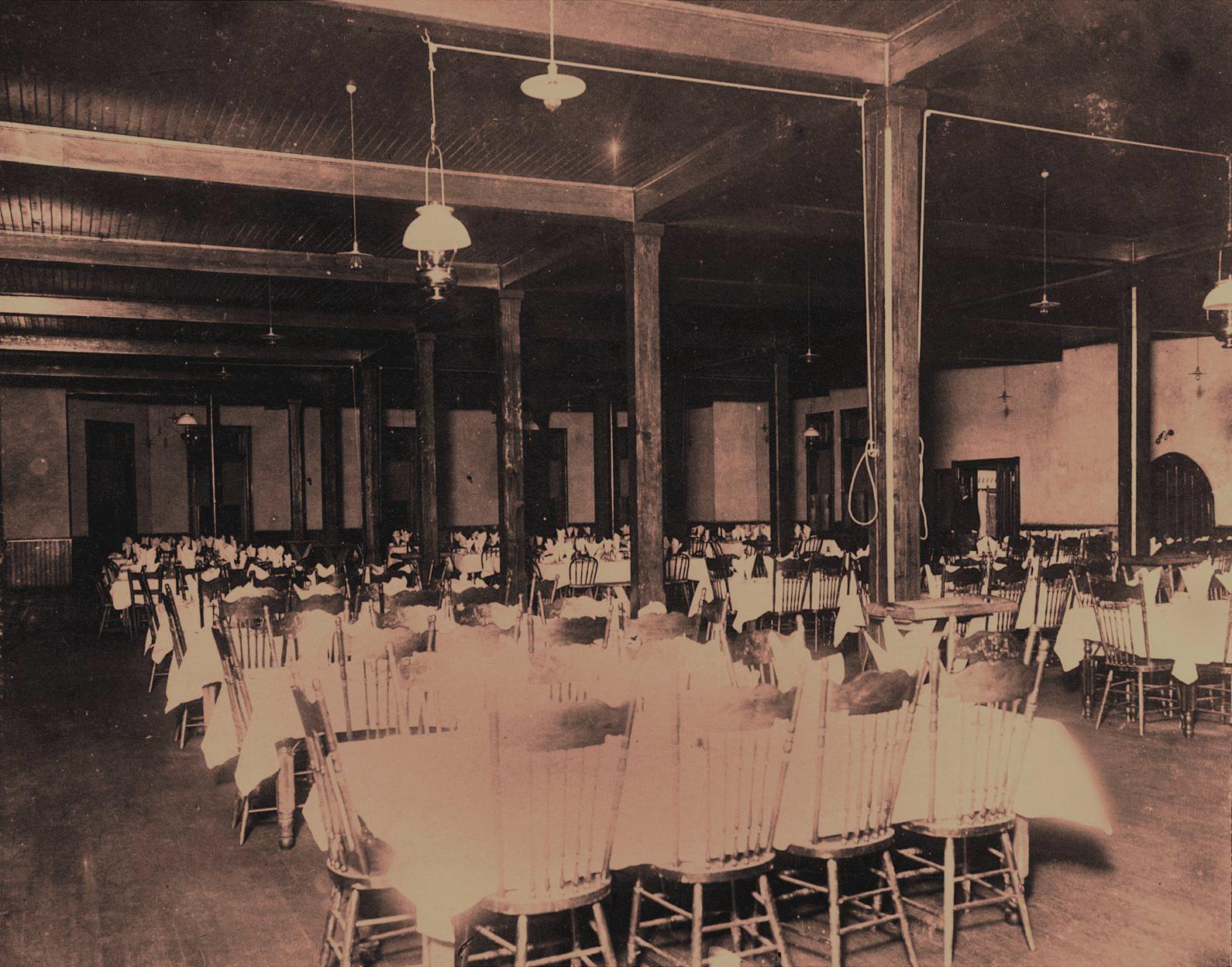

As there were initially no dining facilities on campus, students took meals with local families or at the nearby Lusters Hotel. Others formed their own private messes to provide for themselves. By mid-1873, however, the college had erected a mess hall; after the addition of more lodging in 1881, the school required all students to live and eat on campus.

The fare in the early mess halls could best be described as basic, and though the college claimed to make every effort to provide good materials, and to have them properly cooked and neatly served, the mess didnt have the reputation of todays Virginia Tech Dining Services for culinary excellence. In the 1881/82 catalog, administrators noted apologetically, [N]ecessarily, the living at seven and a half dollars per month must be plain. After one too many poorly prepared meals, one student expressed the frustration of many when he wrote in the 1900 Gray Jacket: I am so weary of sole-leather steak / Petrified doughnuts and vulcanized cake / Weary of paying for what I dont eat / chewing up rubber and calling it meat.

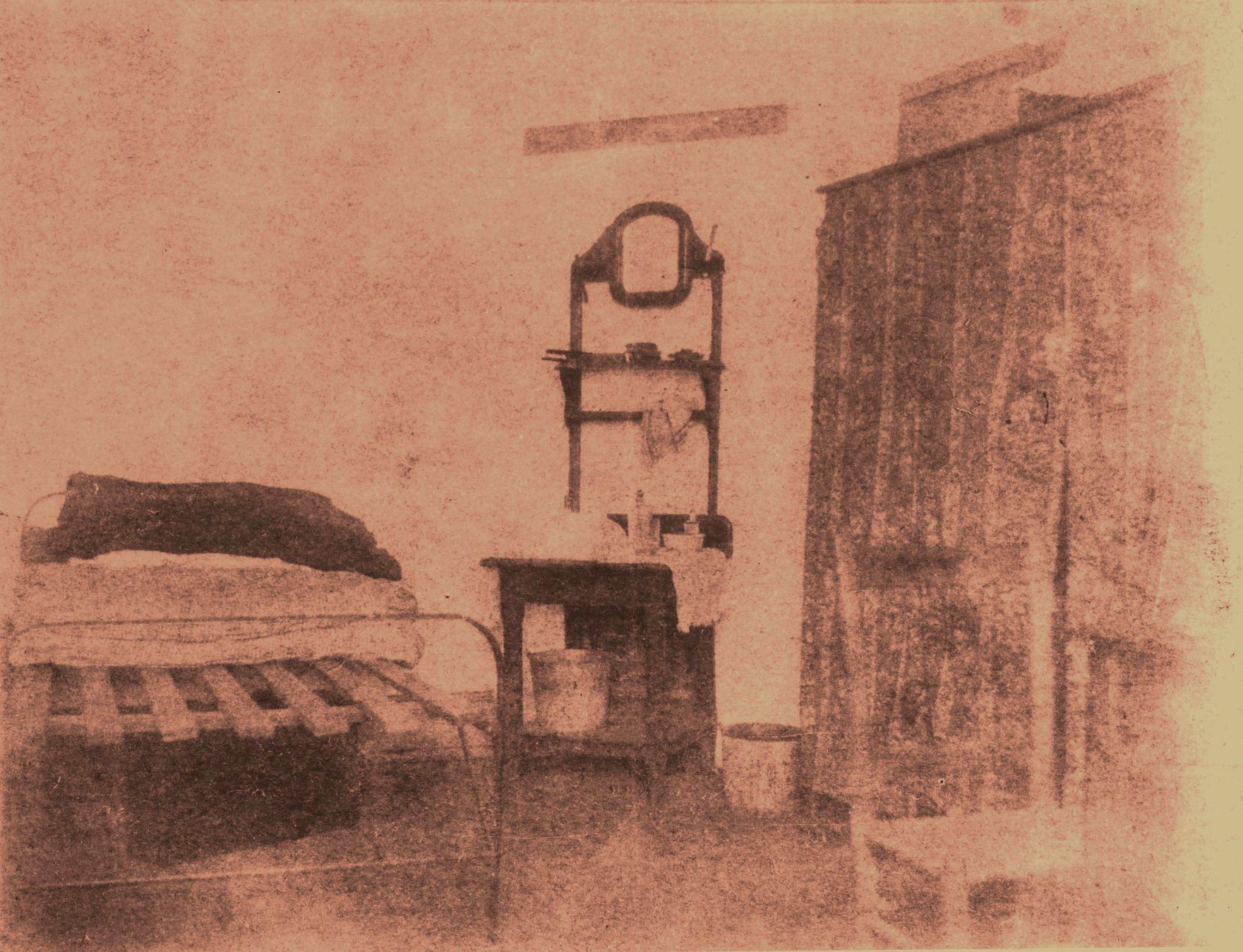

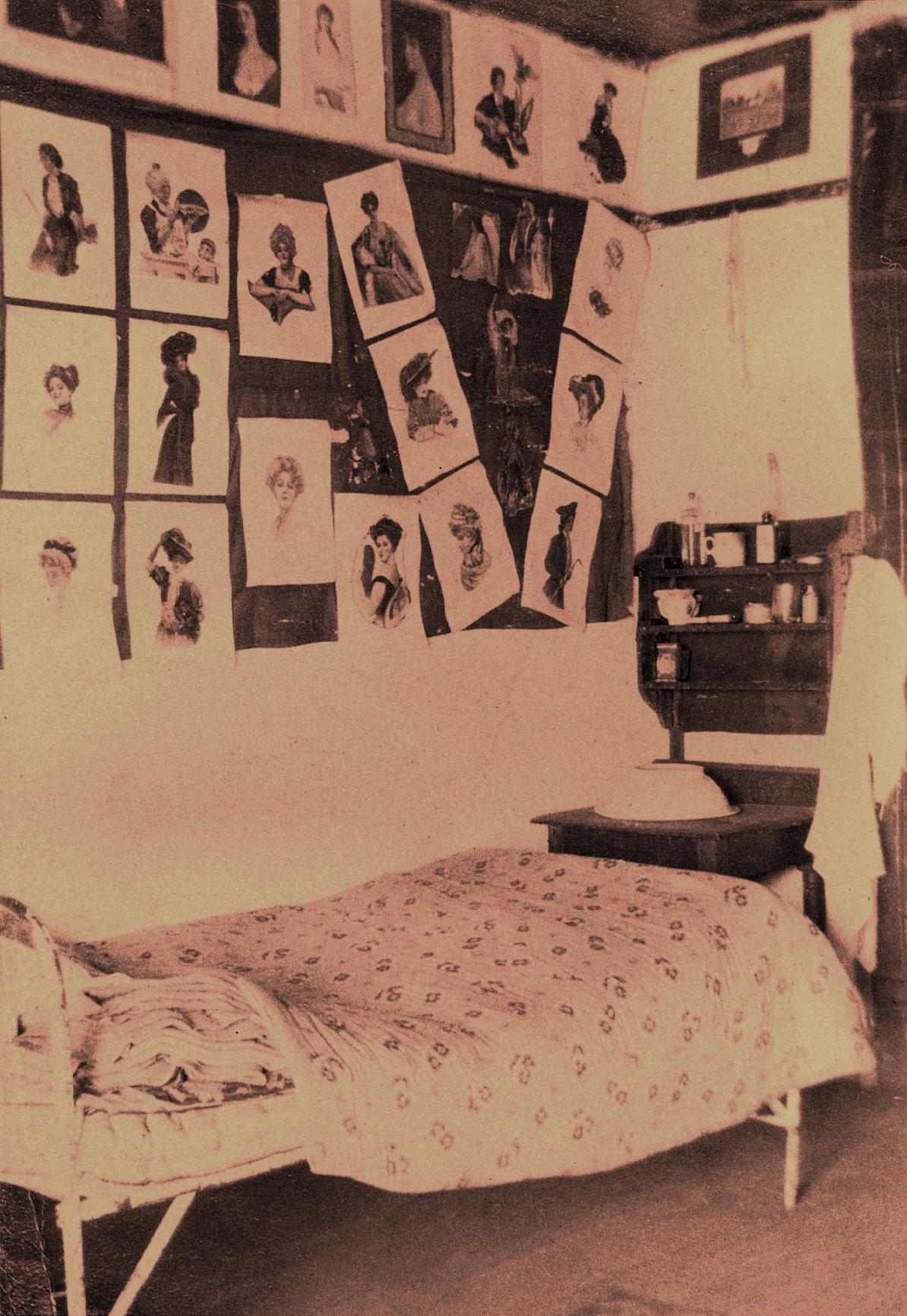

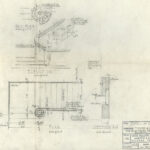

1888 saw the opening of Lane Hall (then known as Barracks No. 1), able to house 150 students. While the accommodations were still meager by todays standards, the new building contained such appreciated amenities as steam heating and, on the ground floor, hot and cold running water. Electric lighting was added in 1890. The furnishings, made by students in the college shops, included austere bedsteads, tables, chairs, and bookcases. Students provided their own mattresses, linens, water- and slop-buckets.

As with students immemorial, the VAMC cadets participated in many unauthorized activities and pranks. Though regulations forbade it, they drew water from the barracks radiators to fill the washtubs in their rooms for a hot bath on Saturday nights. And with the new availability of its primary ingredient, the water bomb soon became a campus mainstay, to the chagrin of pedestrians near the barracks.

The housing of all students under one roof brought with it unintended results. Hazingor the “application of extra-curricular controls over the behavior of the freshmen, as Douglas Kinnear called it in his 1972 history of Virginia Techbecame ritualized after the construction of Lane Hall and probably caused many a first-year cadet to wish hed never heard of Blacksburg.

Despite all of the inconveniences and discomforts endured by the new students, they came to love their school devotedly and, as alumni, to remember it fondly and support it proudly. It must have been exciting for that first generation of students to watch the continual improvements made in the campus and to see it grow into the university it had become by the mid-20th century. There can be no doubt, though, that when they visited, they could be heard to comment upon how easy their successors had things.

The University Archives contain a wealth of materials that offer glimpses into the early days of Virginia Tech. The photographs, campus maps, student scrapbooks, and published histories in our collections trace the schools evolution from a one-room school to the dynamic, modern research university that it is today.

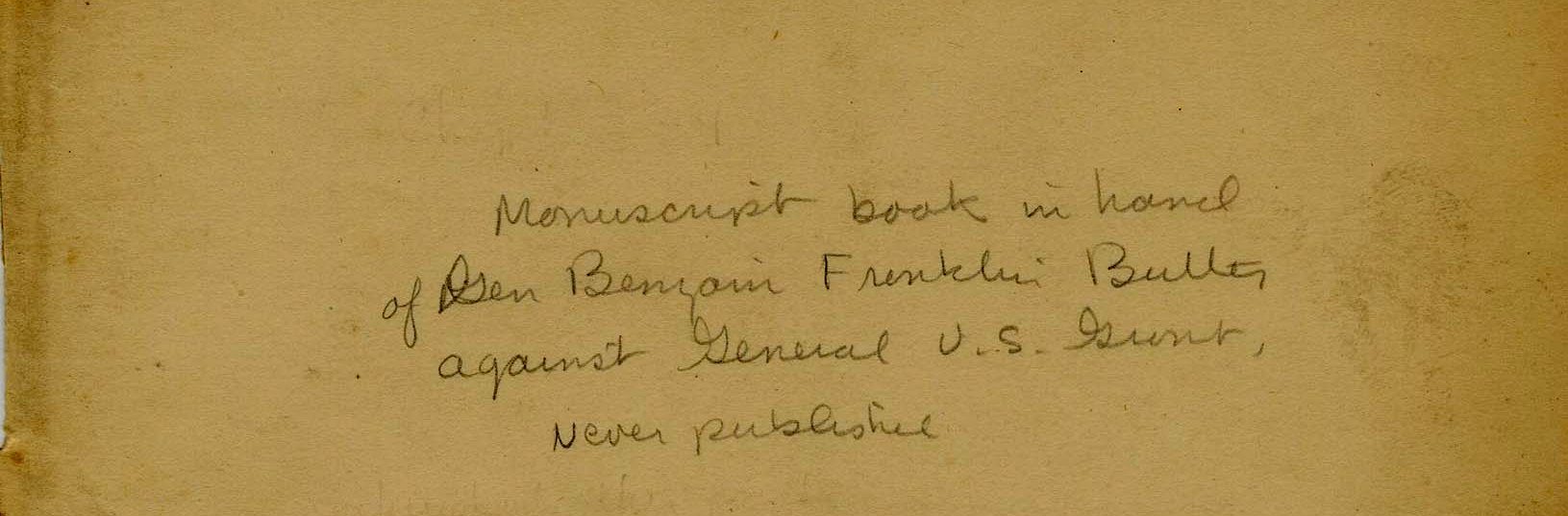

![Typical of the writer's charges against Grant is this passage, in which he charges Grant with absenting himself from his duties: "Grant, as usual, did nothing and saw nothing. . , as he was more comfortable at his head-quarters. . . he left his troops for pure Havans and champaign [sic], the green tree and delicious reveries in a recumbant [sic] position...](https://scuablog.lib.vt.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/butler002.jpg?w=238)

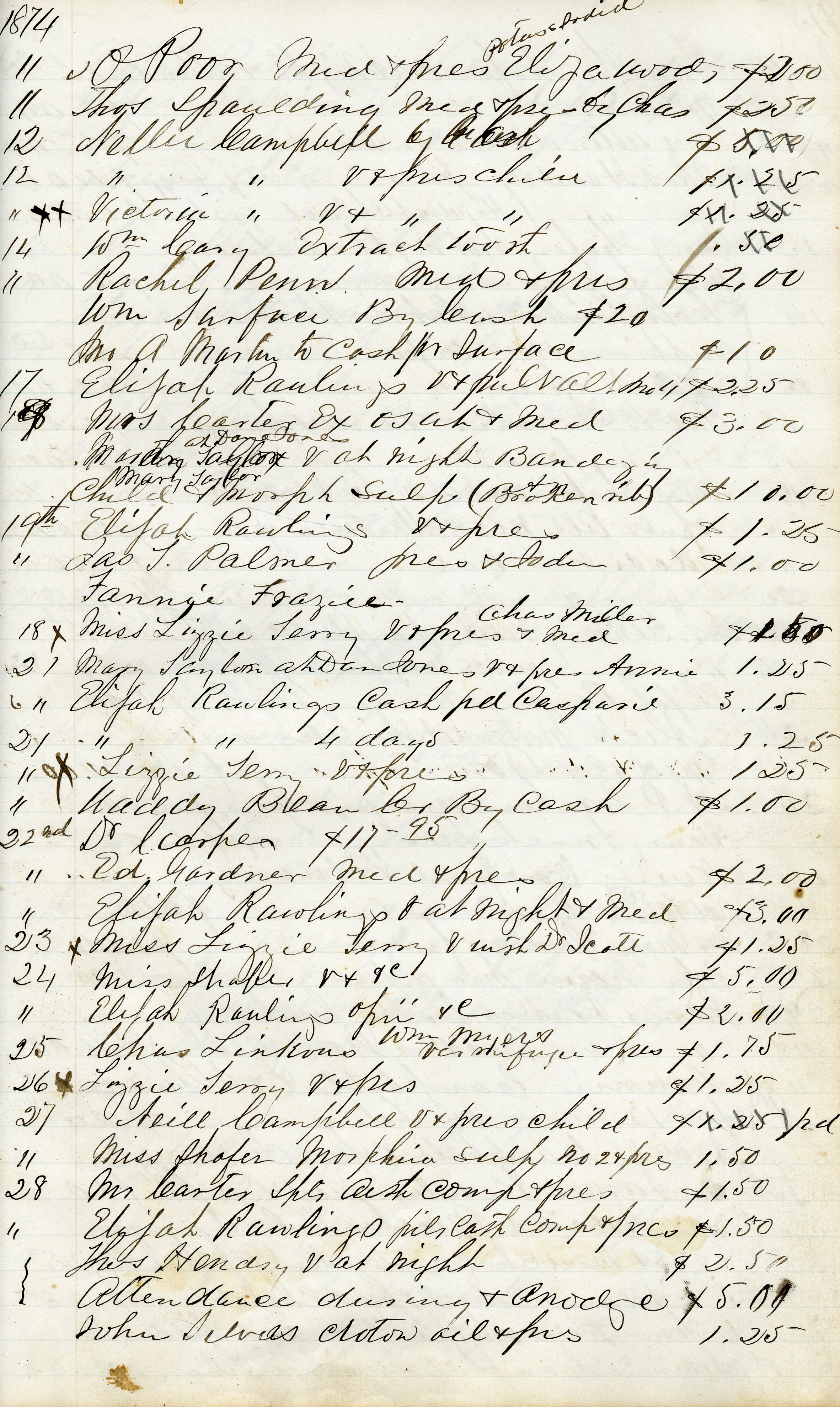

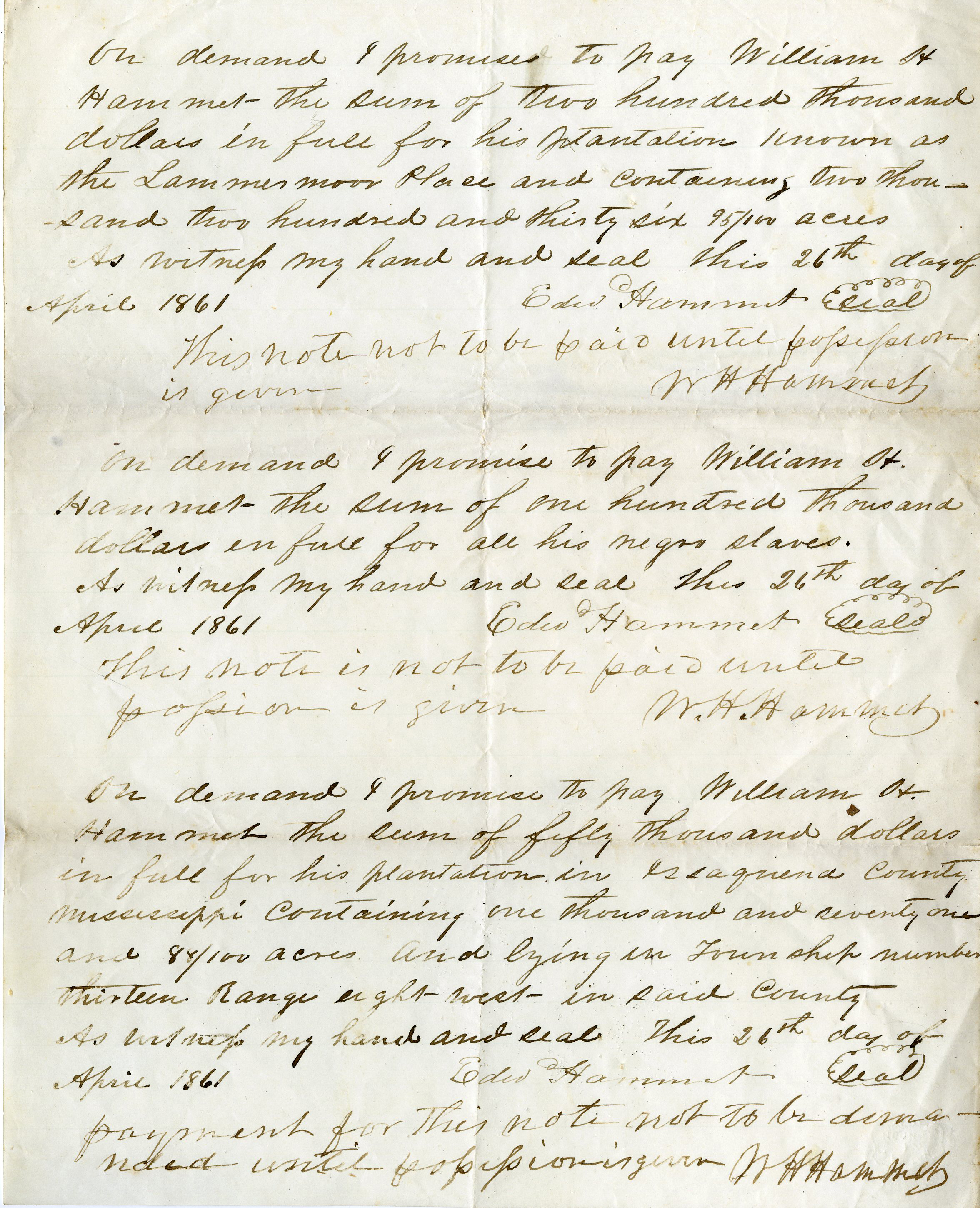

![A sample page from William Hammet's medical practice account book. The first entry, from March 10, 1837, reads, "Col. Pursey To seting [sic] fractured leg for negro + 3 subsequent visits for [ditto] [$]50--." The larger handwriting at bottom left is that of Governor Tyler, who used this and other account books of the Hammets to record his own business transactions some decades later.](https://scuablog.lib.vt.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/hammet003.jpg?w=245)

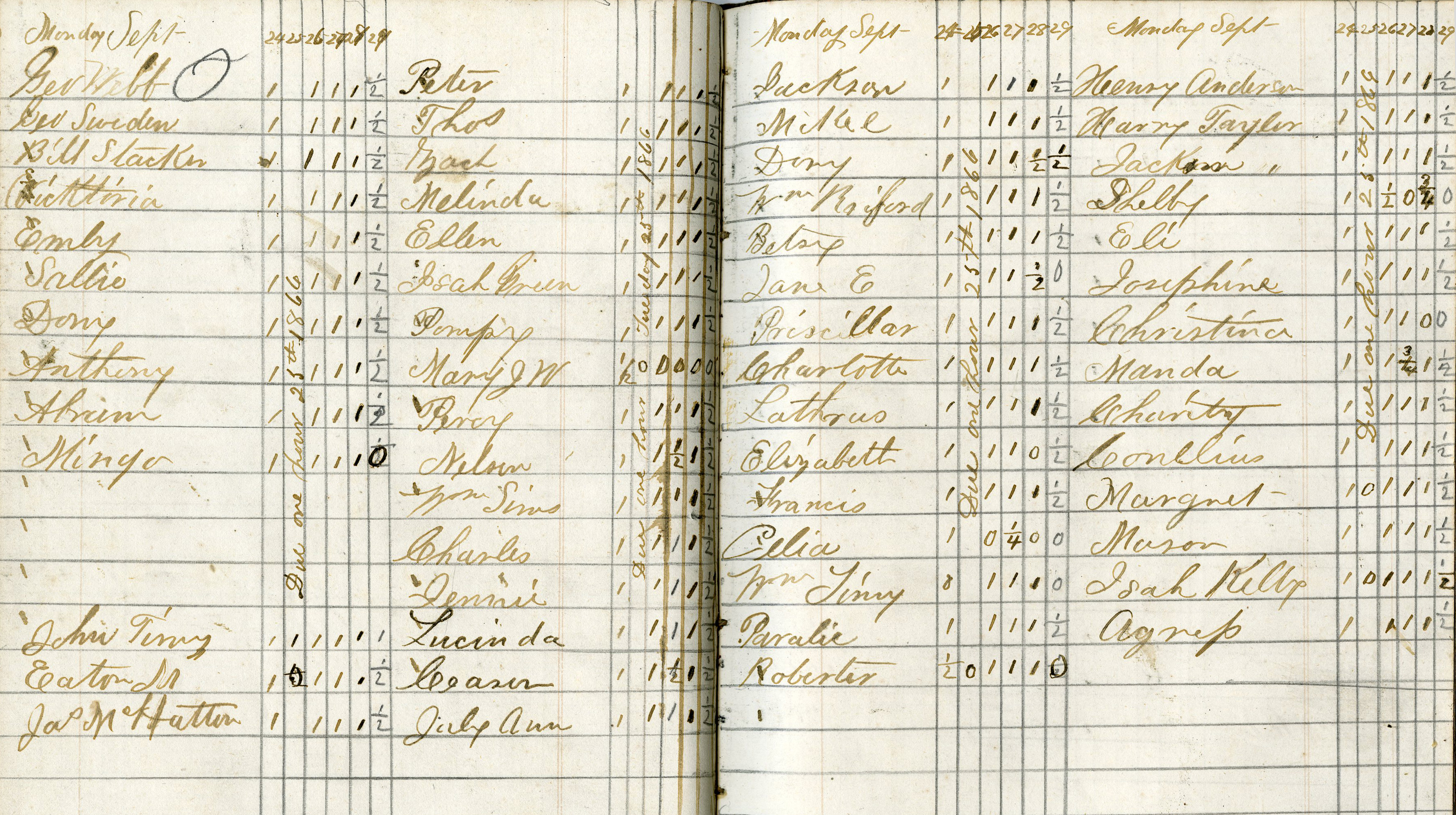

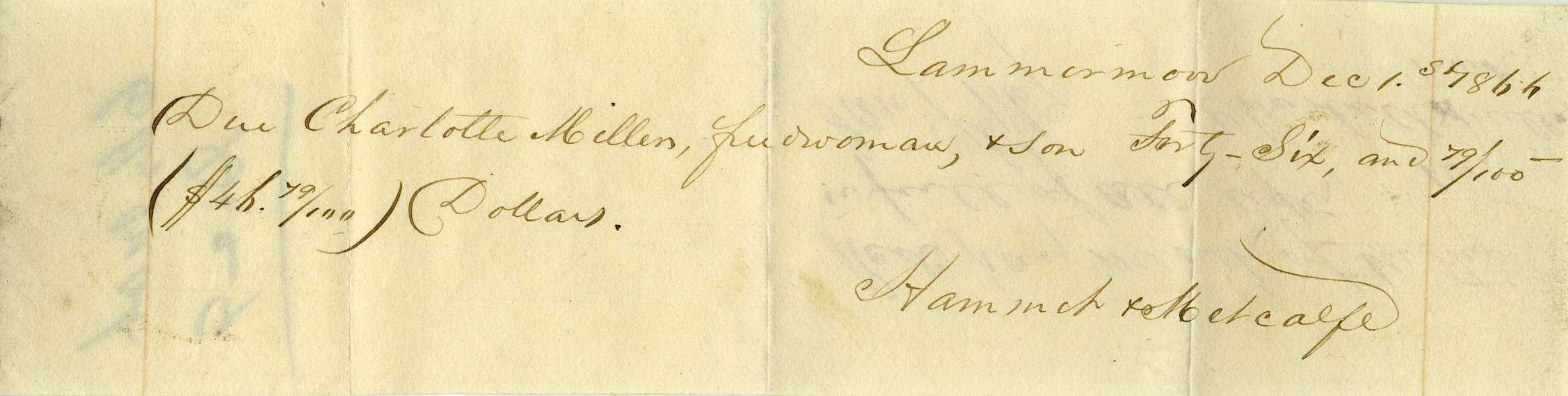

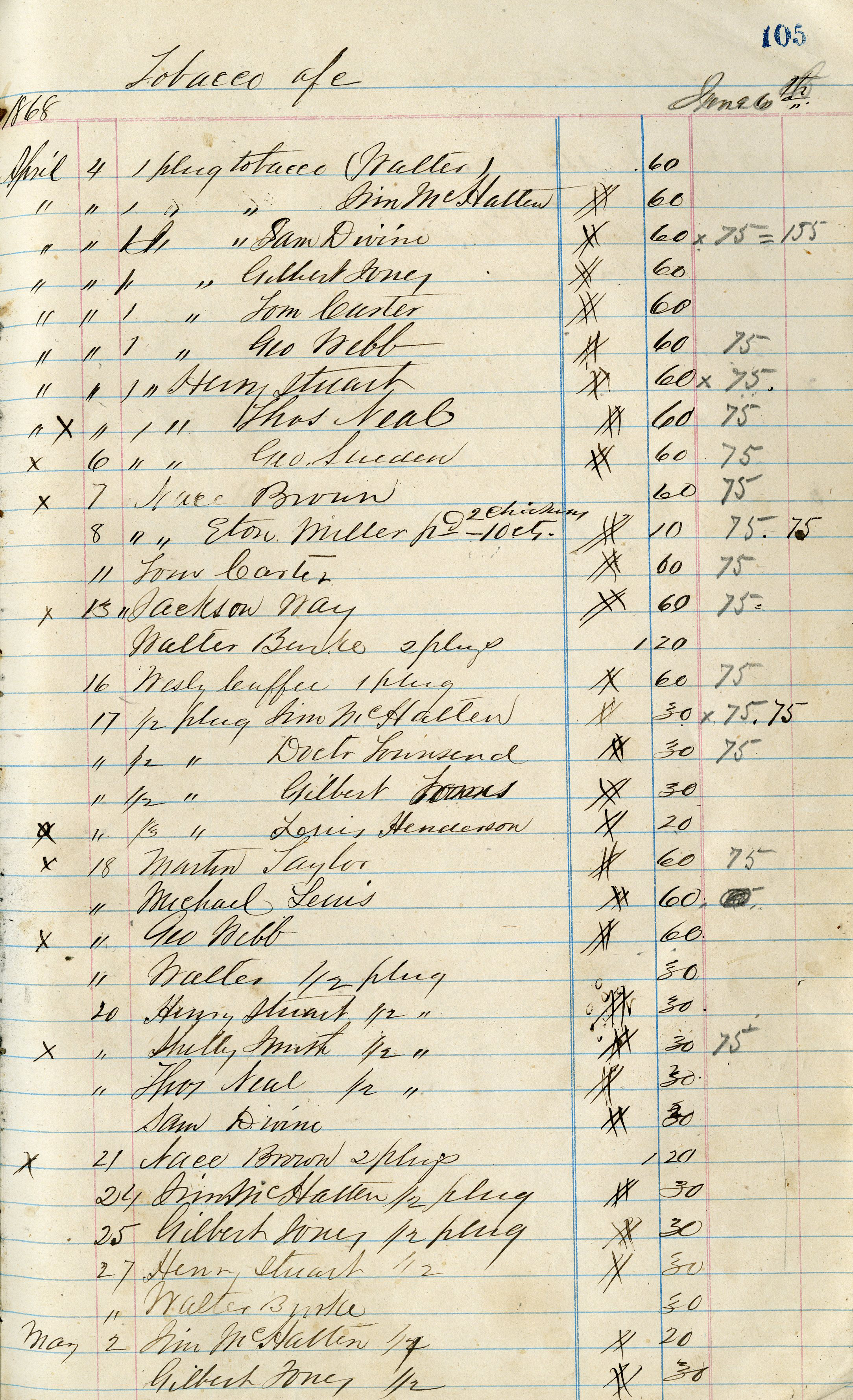

![Many of the journal entries made by James P. Hammet while managing operations of Lammermoor relate to fines he imposed on freedmen working at Lammermoor. The entry for March 30, 1866 reads: "Isaiah Green Wm Rayford overturned a wagon, Bale of Hay in water... By [cause?] - Carelessness - Refused to pick it up - laid over night. Damages $10-." Elsewhere Hammet says of the workers, "A more triffling [sic] set never were congregated together."](https://scuablog.lib.vt.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/hammet001.jpg?w=300)