The Drillfield is probably the most iconic and storied site at Virginia Tech. The Drillfield has taken many names and shapes over the years and has witnessed almost every turning point in Virginia Tech’s history – protests, tragedies, and anniversaries as well as sleep-ins, pig-roasts, and icy (mis)adventures. The Drillfield has been a part of so many stories on campus that one single blog post cannot capture them all, but lets start at the beginning…

For the first few years of Virginia Tech, there was no drill field of any kind. In the late 1870s, cadets unofficially established a drill field behind the First and Second Academic Buildings (northeast of the current Henderson Hall). As more buildings were constructed and more students arrived, that drill field was extended north towards Upper Quad (behind Lane Hall) and later even further extended towards today’s Shanks Hall. During the 1880s and 1890s, Blacksburg residents would gather to watch the cadet’s drill exercises, parades, as well as all the new baseball and football games happening.

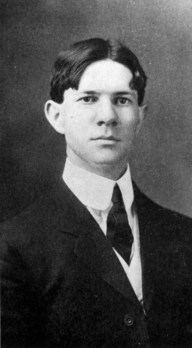

Dr. Edward Ernest Sheib, circa 1890s

Cadets on Sheib Field, circa 1899-1900

Baseball game on Sheib Field, circa 1895

1896 football team on Sheib Field

Until 1894, the area that is the present-day Drillfield was used mostly for the college farm and garden plots. In 1877, a faculty house was constructed at the northeast corner of the present-day Drillfield (later repurposed as the Administrative Building), and in 1888, the Agricultural Experiment Station was built roughly where the April 16th memorial is today. President John McLaren McBryde allocated a part of the college farm for the cadets’ drills and athletics in 1894 with the help of the newly formed Athletic Association. This field (i.e., the first rendition of the present day Drillfield) was originally called Sheib Field after Professor Edward Ernest Sheib who taught History, English, and Political Economy at Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College (VAMC – Virginia Tech’s first name). Professor Sheib was also on the Board of Directors for VAMC’s Athletic Association and the main financial supporter of the football team.

Sheib Field quickly became the new favorite spot for watching the cadet drills and parades as well as cheering on the baseball and football teams. The first football game on Sheib Field happened on October 20, 1894 against Emery and Henry College (now Emery and Henry University). The final score was VAMC, 16 – Emery and Henry 0, a great first game and victory on their new athletic field. The previous drill field was still in use, mostly for interclass games and practices or new sports at VAMC like tennis. Sheib Field was often referred to as both the Athletic Field and the drill field to distinguish which parts of the field were used for what activities.

Sheib Field soon was used for major events and celebrations, such as commencement processions, Field Day, and George Washington’s birthday. At the end of each academic year, cadets would put on a “mimic battle” (also called a sham battle) at Sheib Field, where spectators could watch the cadets stage a pretend or recreation of a historical battle to practice their skills and maneuvers. By the turn of the century, much of the present-day Drillfield was still not developed and was being used for garden plots for the Horticultural Department. However, in 1900, the Athletic Association did construct a quarter-mile track around Sheib Field, though a varsity track team would not be established until 1906. Sheib Field still had a long way to go – half the field was six feet lower than the other half and there were no stands at the time for spectators. In 1901, the Horticulture Department moved some of its garden plots to behind the college orchard, which freed up space to expand Sheib Field west.

With the new expansion came a new name for the field. Sheib Field was renamed Gibboney Field in 1902 to honor James Haller Gibboney (class of 1901), who was the first Graduate Manager of Athletics at Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College and Polytechnic Institute (VPI – Virginia Tech’s second name).

James Haller Gibboney, 1901

The Snow Battle of 1908 on Gibboney Field

In that same year, a wooden stand was built by the track to seat spectators, encircling the south side of the newly named Gibboney Field (still referred to colloquially as the Athletic Field for sports and the Drillfield for drills). More permanent stands were constructed the next year to try and keep up with the growing number of Hokie fans. Between 1902-1909, Gibboney Field underwent small repairs and maintenance, starting with moving the last of the Horticulture Department’s Garden plots to the north of present-day Derring Hall. In the fall of 1904, Gibboney Field held over 1,000 spectators for the NC State vs VPI football game. By the 1905 season, Gibboney Field had 3,000 spectators for the UVA vs VPI football game. Despite a $1,600 renovation in 1906, Gibboney Field needed even more work, including a new drainage system, grandstand, and re-grading.

Again, with these major renovations, a new name was given to the field – Miles Field. During its time as Miles Field, students also called it Miles Meadow, the Athletic Field, and the drill field depending on what part of the field they were referencing. Miles Field was named in honor of Clarence Paul “Sally” Miles, who served as the captain of the baseball team when he was a student, VPI’s head football coach, baseball coach, and later Athletic Director.

On the newly renovated Miles Field, VPI held its first Pep Rally on October 30, 1909. That same year, the annual Engineering vs Agriculture faculty football game began. In addition to the new traditions, Field Day, the annual Snow Battle, and numerous Dress Parades continued at Miles Field, cementing itself as the center of campus life at VPI.

Field House, circa 1915

Track meet on Miles Field, circa 1923

“Sham Battle” on Miles Field, 1914

Miles Field, circa 1910

In November 1914, only 60 feet from the football field, the Field House was completed, the first building on campus used mainly as a gymnasium. Occasionally, the Field House was used for dances and briefly as an infirmary during the 1918-1920 flu pandemic, but mainly was meant for athletics. Miles Field was starting to take the iconic oval shape – with the track, Library, Administrative Building, Agriculture Experiment Station, and the Field House outlining the field.

During this time, Blacksburg High School athletes (both boys and girls) also played on Miles Field during the school year and borrowed the Field House during the winter. Miles Field even became the site of alum events, such as the Alumni Parade and reunion games.

World War I drastically changed how Miles Field was used. The 1917-1918 school year saw major changes to the curriculum that included almost daily drills and field maneuvers in anticipation for joining the war. The number of athletes was noticeably smaller that year; however, spectators still turned out to games in droves despite ticket sales being taxed to help fund the war effort (season tickets at the time cost $5.00). In the fall of 1918, Miles Field witnessed the new Students’ Army Training Corp implemented by the United States Army.

On November 11, 1918, with the pandemic under control in the Blacksburg area and the war over, VPI held a formal parade on Miles Field to celebrate.

General maintenance and upkeep of Miles Field continued over the next few years. By 1921, Miles Field was drastically regraded due to the Cadet Band having trouble marching over the uneven turf. Consequently, a master plan for Miles Field was underway in 1922 by architect Warren Manning. This plan decided to formally separate the athletic field and drill field, so a committee of the Athletic Council approved creating an athletic stadium 200 yards away from Miles Field. Built in sections and funded by class donations, Miles Stadium was built and housed football, baseball, and track events until 1926.

To avoid confusion with the new stadium complete, a new name was needed for the old Miles Field – the Drillfield. Miles Field was no longer used as an athletic field, so the track and grandstand were ripped up, and all parts of the field were combined into one large expanse.

VPI development plan, 1927

Proposed plan for VPI campus, 1925

However, to the dismay of the drill-weary cadets, President Burruss wanted to name the Drillfield the “Recreation Field.” On maps of campus at that time, the Drillfield was labeled as the Recreation Field, but students continued to call the area the Drillfield as seen in student publications.

One downside to expanding the Drillfield was heavy rain caused the field to become so muddy, the laundry services on campus could not keep up with the demand. The mud-filled Drillfield quickly earned the name “Begg’s Lake” after the civil engineering professor, Robert B.H. Begg, who oversaw the re-grading of the Drillfield. Nevertheless, VPI continued to work on the Drillfield for the next few years and throughout the 1930s. Struble’s Creeks, which ran by the War Memorial Hall, was diverted using a concrete culvert in 1934. By the end of the 1930s, the moniker “Begg’s Lake” was no more thanks to all the excavation, drainage, and grading done.

One proposed plan for the Drillfield was to add a pool or lake at the lower end of the Drillfield fit for “boating and swimming in the summer and skating in the winter”. This plan was nixed when an engineering professor pointed out that the water would quickly become polluted and muddied. This proposed plan eventually morphed into what is the Duck Pond today.

For the next few decades, the Drillfield remained what President Burruss had envisioned, the heart and soul of modern-day campus of Virginia Tech. Hokie-stone buildings were erected surrounding the field, such as Burruss Hall, Patton Hall, and Williams Hall. Parking spaces were added all around to compliment the new roadway. In 1960, the War Memorial Chapel was completed on the north side of the Drillfield. It was not until the summer of 1971 that two asphalt walkways were laid across the Drillfield. After the tragedy on April 16, 2007, the Drillfield became a permanent site of mourning and remembrance for the university with the construction of the April 16 Memorial and Memorial Benches. In 2015, more walkways were added, using 14 different materials as part of a project to develop a new master plan for the Drillfield. While still ongoing as of 2024, the plan’s focus is on preserving the field while making it as usable and accessible for everyone.

Virginia Tech campus map, 1952

Virginia Tech campus map, 1958

Drillfield, 1963

Virginia Tech campus map, 2024

References:

Cox, Clara B. (2008). The Drillfield: at the heart of campus. Virginia Tech Magazine, 30(2). Retrieved from https://www.archive.vtmag.vt.edu/winter08/feature1.html.

Kinnear, D. L. (1972). The First 100 Years: A History of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Virginia Polytechnic Institute Educational Foundation, Inc.

Robertson, Jenkins M. (1972). Historical Data Book: Centennial Edition. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Temple, Harry D. (1996). The Bugle’s Echo: A Chronology of Cadet Life at the Military College at Blacks, Virginia, The Virginia Polytechnic Institute. The Virginia Tech Corp of Cadets, Inc. vol. I-V

Wallenstein, Peter. (2021). Virginia Tech Land-Grant University 1872-1997: History of a School, a State, a Nation. 2nd ed. Virginia Tech Publishing.

All images included in this blog post can be found in our Historic Photograph Collection or at Special Collections and University Archives Online.

Like this:

Like Loading...