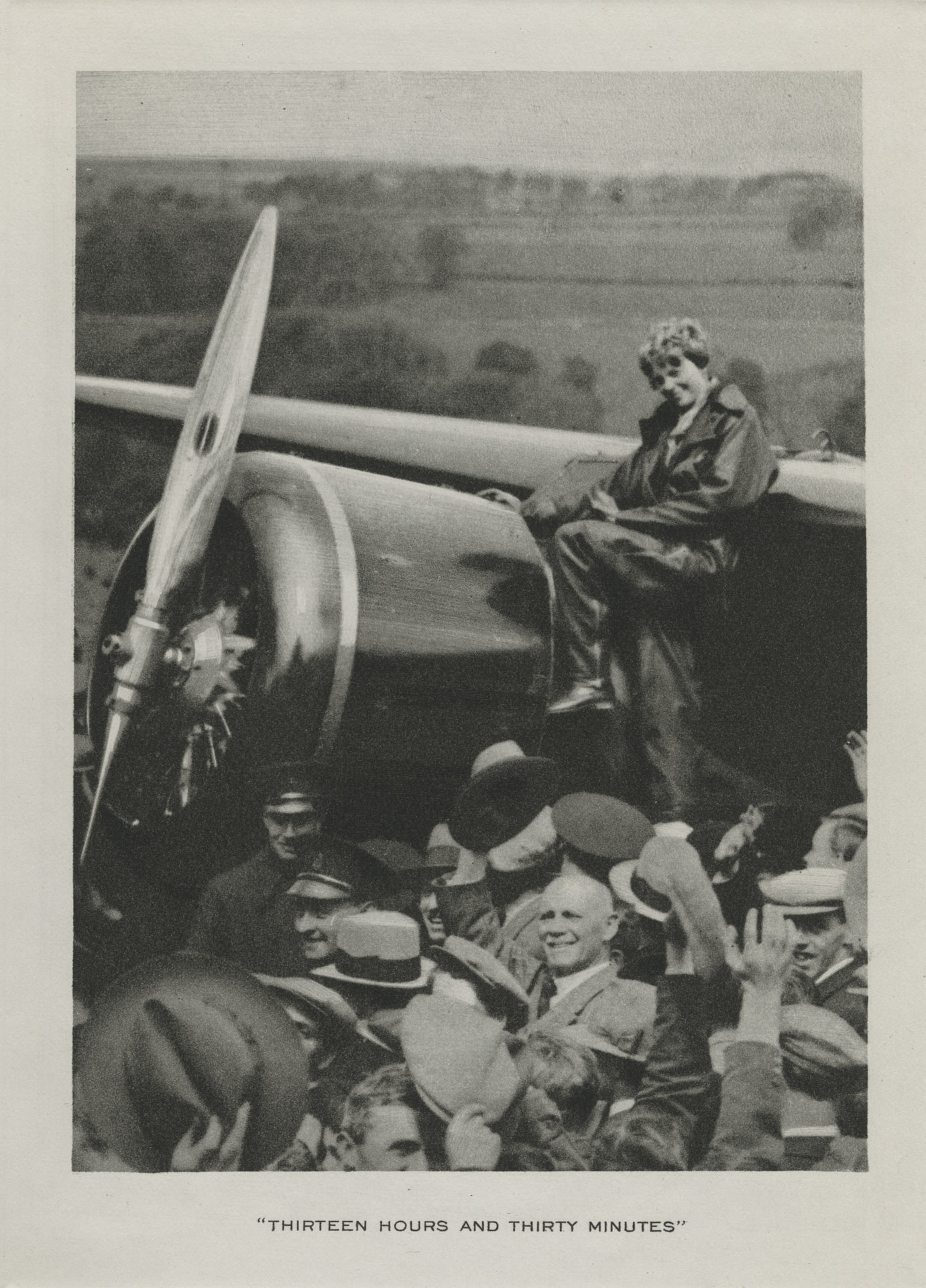

A Souvenir Menu Recalls Earharts Triumphant Return to the U. S.

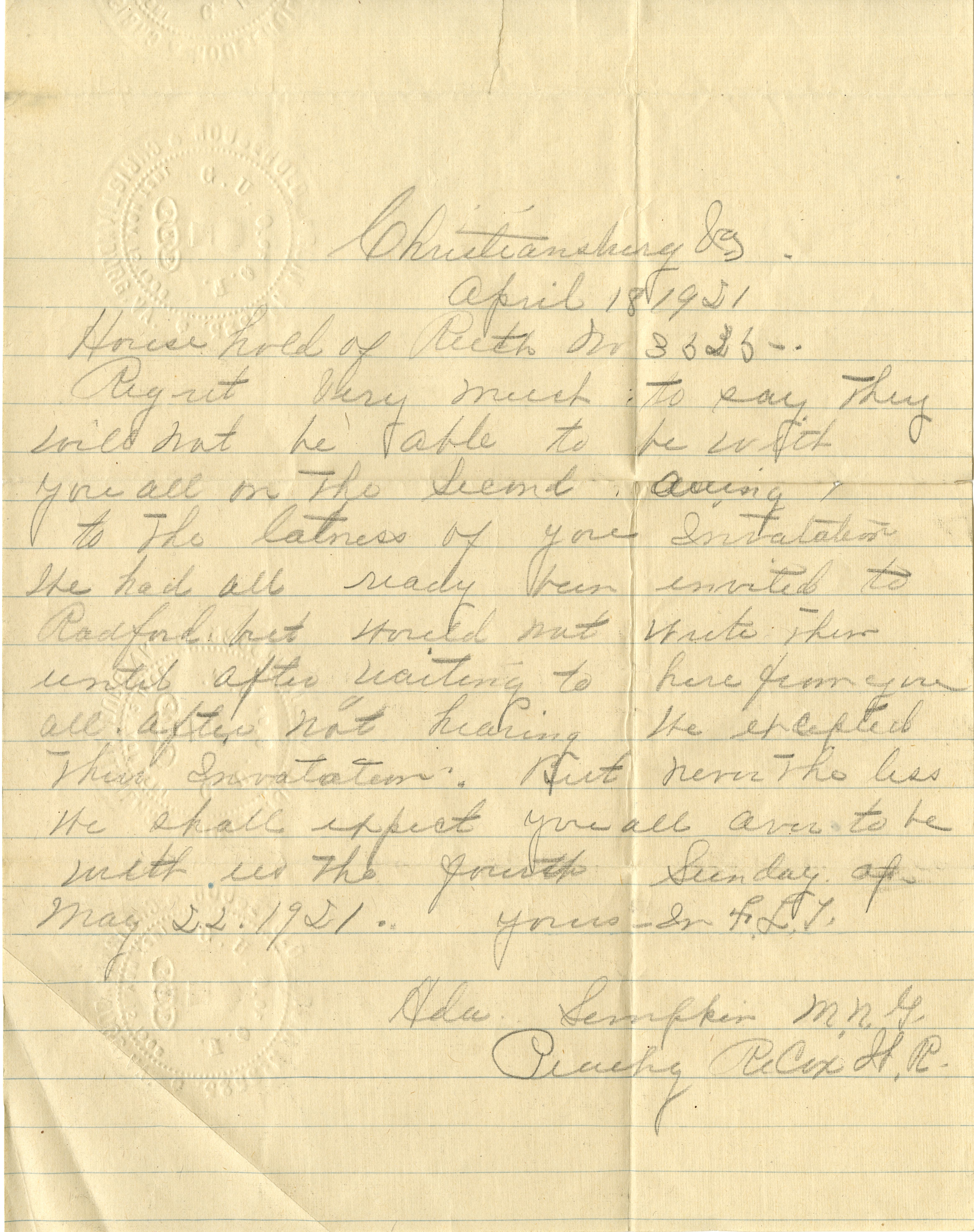

The recent reports about possible new evidence in the 80-year mystery of Amelia Earharts disappearance reminded me of a little item in our collections: a menu for a 1932 dinner honoring the pilot. Housed, perhaps incongruously, within our Aviation Pamphlets and Brochures Collection (Ms1994-015), this souvenir commemorates a milestone in aviation and womens history.

Though Amelia Earharts name endures, it may be difficult for us to imagine today the level of fame she attained through her derring-do. The word icon has perhaps been devalued through overuse in recent years, but Earharts solo crossing of the Atlantic made her a true icon and arguably the most famous woman of her time.

Even before Earhart undertook her solo transatlantic flight in 1932, she had gained fame through her feats: as the first woman to cross the Atlantic via airplane (1928), as the first woman to make a solo transcontinental roundtrip flight across the U. S. (1928), and as the record holder for the highest altitude attained in an autogyro (1931). Despite occasional criticisms leveled against her skills as a flyer, Earhart through her personality and her penchant for self-promotion put a face on womens advances in fields that previously had been reserved for men.

Earhart departed Newfoundland on May 20, 1932 and landed in Ireland the following day, exactly five years after Charles Lindberghs historic solo flight across the Atlantic. While most know that Earhart was the first woman to make such a flight, few may remember that no pilot had successfully made a solo transatlantic flight in the five years after Lindbergh.

In the following weeks, Earhart toured Europe, receiving a number of honors and being feted by various dignitaries. After several weeks of enjoying her celebrity, Earhart embarked for home. Despite her accomplishment, transatlantic flight remained a dangerous undertaking reserved for pioneering daredevils. (The transatlantic passenger service established by Germanys Graf Zeppelin in 1928 averaged only about 20 flights per year for the next decade. Weather and distance would prevent the commercial viability of transatlantic passenger plane flights until the late 1930s.) The singularity of Earharts feat is underscored by the fact that she returned to the U. S. via cruise ship.

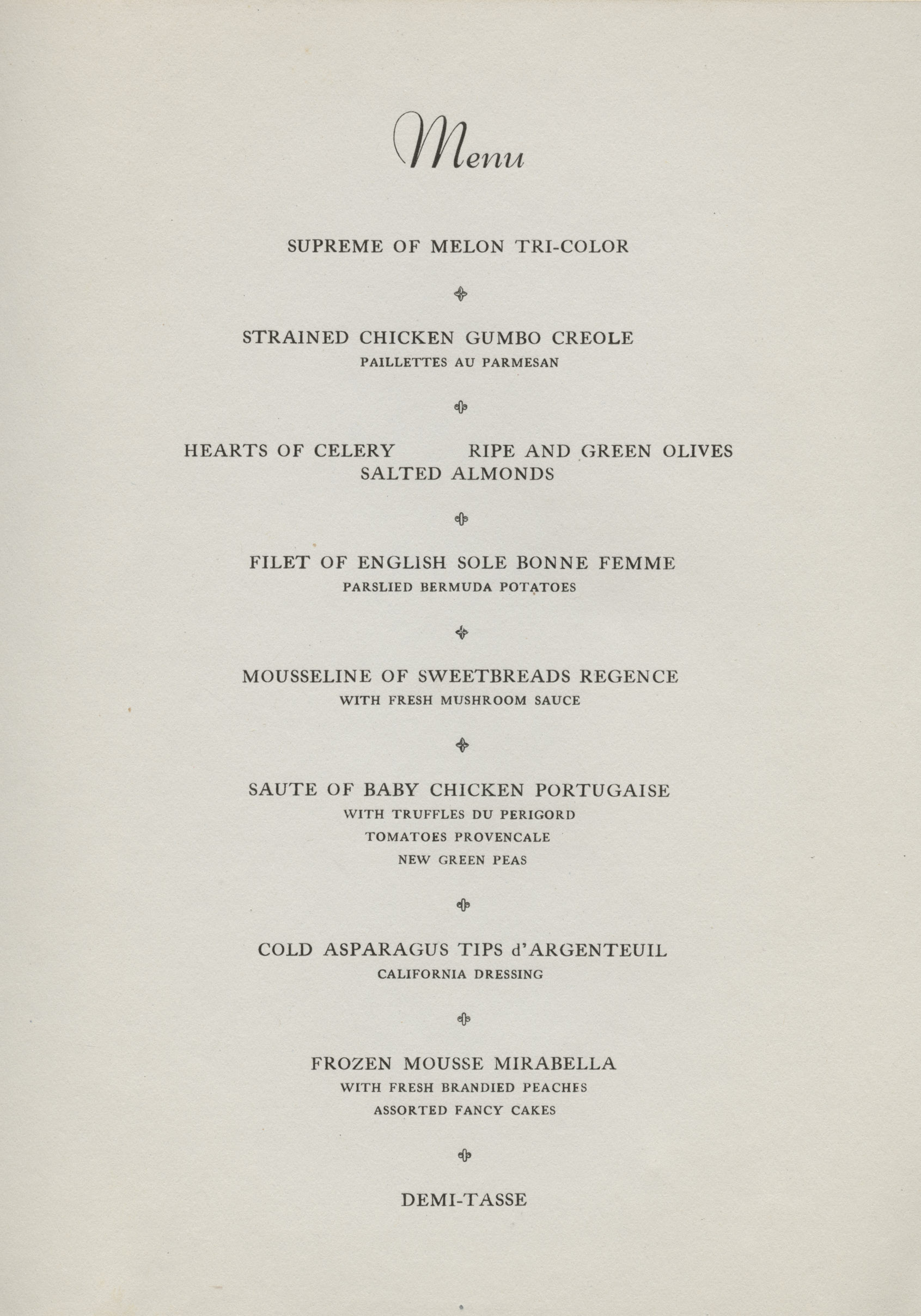

With the country in the throes of the Great Depression, Earhart had asked that her welcome home be an understated affair, but it was perhaps because of the desperate need for something to celebrate that the flyers request went unheeded. When the Ile de France arrived in New York on June 20, it was greeted by all the fanfare the city could muster, including a tickertape parade. Following a luncheon hosted by the Advertising Federation Convention and several rounds of interviews, the days activities concluded at the Waldorf-Astoria, where a full-course dinner was held in Earhart’s honor. Speakers included Charles Lawrence, president of the Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce of America; Don Brown, president of Pratt & Whitney Aircraft; W. Irving Glover, second assistant postmaster of the United States; and Earhart herself. The speeches were broadcast nationwide via radio.

Unfortunately, as far as I was able to determine (in an admittedly cursory search), Earharts words that night seem to have gone unrecorded. She reportedly recounted the experiences of her flight. Perhaps she also repeated some of the responses she had given earlier that day to critics who derided her flight as a non-event. In interviews, Earhart said that she regarded her flight as a personal mission, a justification. After she had flown across the Atlantic in 1928 as a passenger, one commentator downplayed the feat, likening her usefulness on the flight to a sack of potatoes.

In The Sound of Wings, biographer Mary S. Lovell writes of Earhart’s solo flight, [T]hough the flight in itself offered no particular breakthrough, the mere fact that there were pilots prepared to risk all to gain records encouraged manufacturers to further technological effort. In the public eye, too, the flight was a triumphant success at a time when newspapers carried daily reports of fatal air crashes. So her success encouraged confidence in aviation as a principle.

Despite her protestations to the contrary, Amelia Earhart had done much more than answer her critics, and the public responded in a big way, as evidenced in a little menu in our little collection.

In addition to the Earhart menu, the Aviation Pamphlets and Brochures Collection contains a number of interesting pieces relating to the first half century of aviation history. For a complete list, see the collection’s finding aid.