In honor of Black History Month, I thought I’d take this week to talk aboutthe Grand United Order of Odd Fellows.If you’ve watched television or attended a moviein the last 50-60 years, you’ve probably seen a reference to Freemasonry or Masons. While the Masons have become a mythic symbol in popular culture that is often associated with conspiracy theories and the Illuminati, they originated like many secret fraternal organizations in a much more mundane environment: essentiallyas a guild or union and likely in the 14th Century (depending heavily on the history you read and what you consider the meaning of “originate”). Over the centuries many similar organizations were formed or broke away from Freemasonry. One such organization was the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows (GUOOF).

According to their organization’s published history, the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows was formed as a fraternal society in similar fashion to other Masonic societies. Its primary defining characteristic was its inclusivity. Anyone was welcome to join regardless of social status. Unfortunately, that inclusiveness led to a division in the order around the topic of race.In 1842/1843 New York, an effort was launched by a group from the Mother A.M.E. Zion Church to found a chapter of the GUOOF in America. They petitioned the current existing Odd Fellows lodges in America (members of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows) but were denied because the petitioners were black. Since one member of the church, Peter Ogden, was a member ofa GUOOF lodge in England, he set sail to secure a charter for a new lodge. On March 1, 1843, the Philomathean Lodge No. 646 of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows was established in New York. From that time on, the GUOOF in America became a fraternal organization with primarily (while not exclusively) black membership.

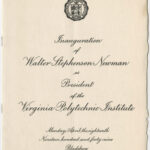

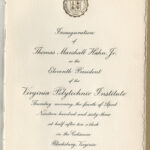

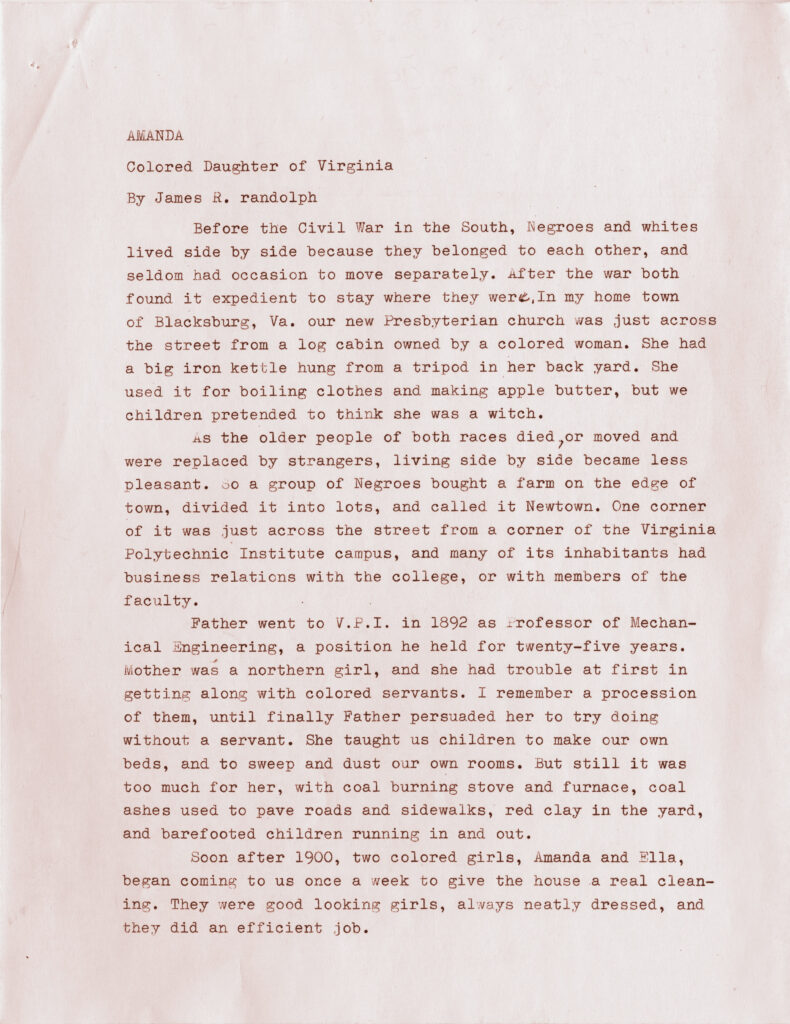

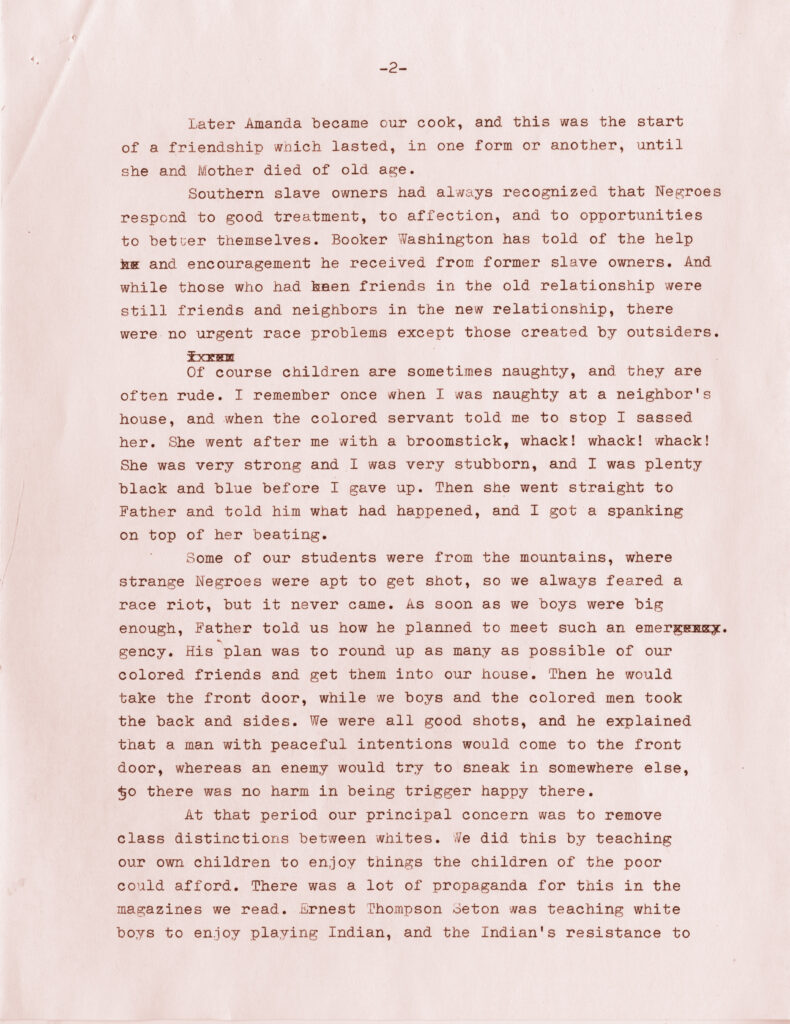

Sometime in the early 1900’s (likely around 1904), Tadmore Light Lodge No. 6184 of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows was founded in Blacksburg, VA. By 1910, their roll showed 23 members.

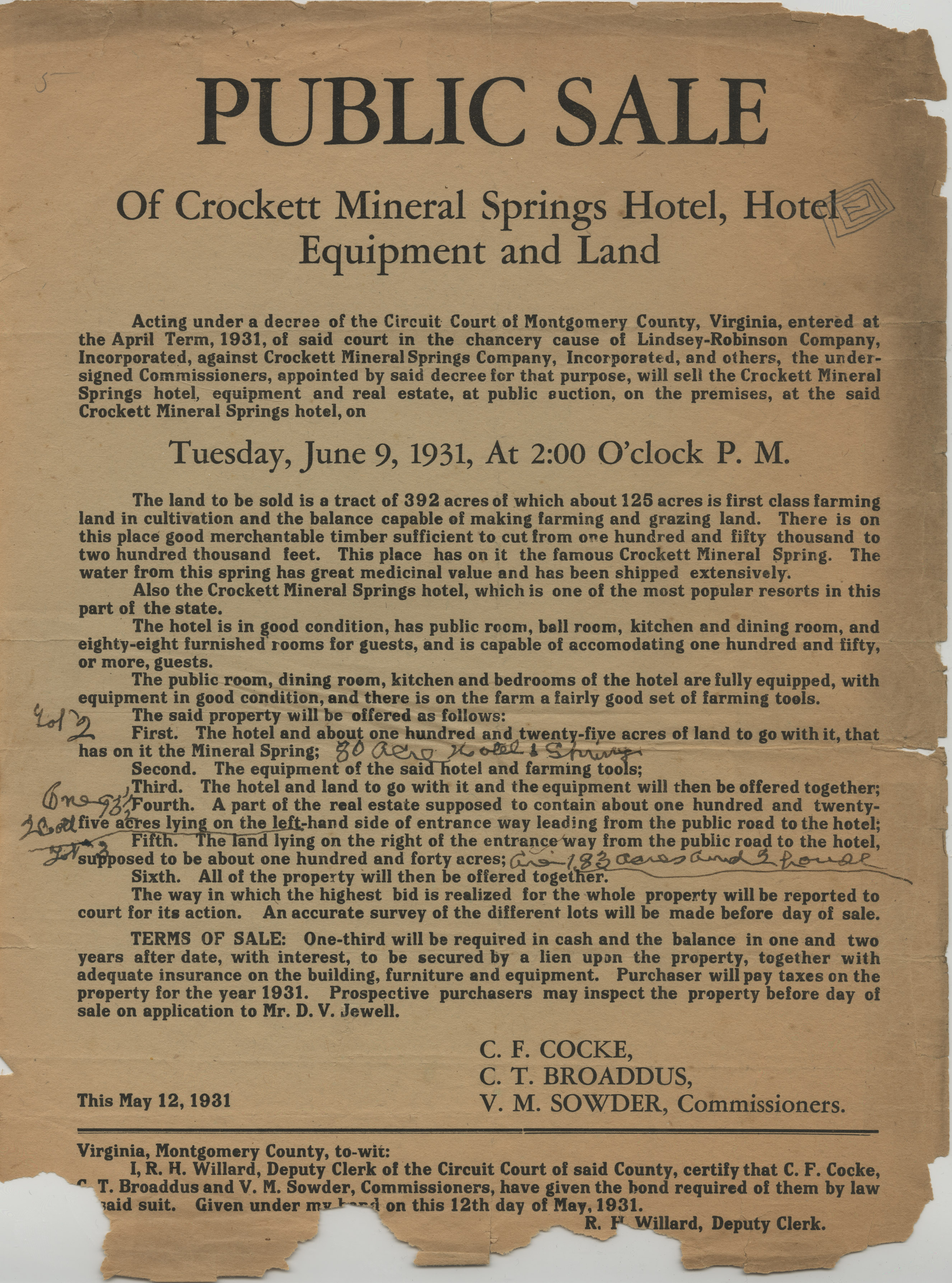

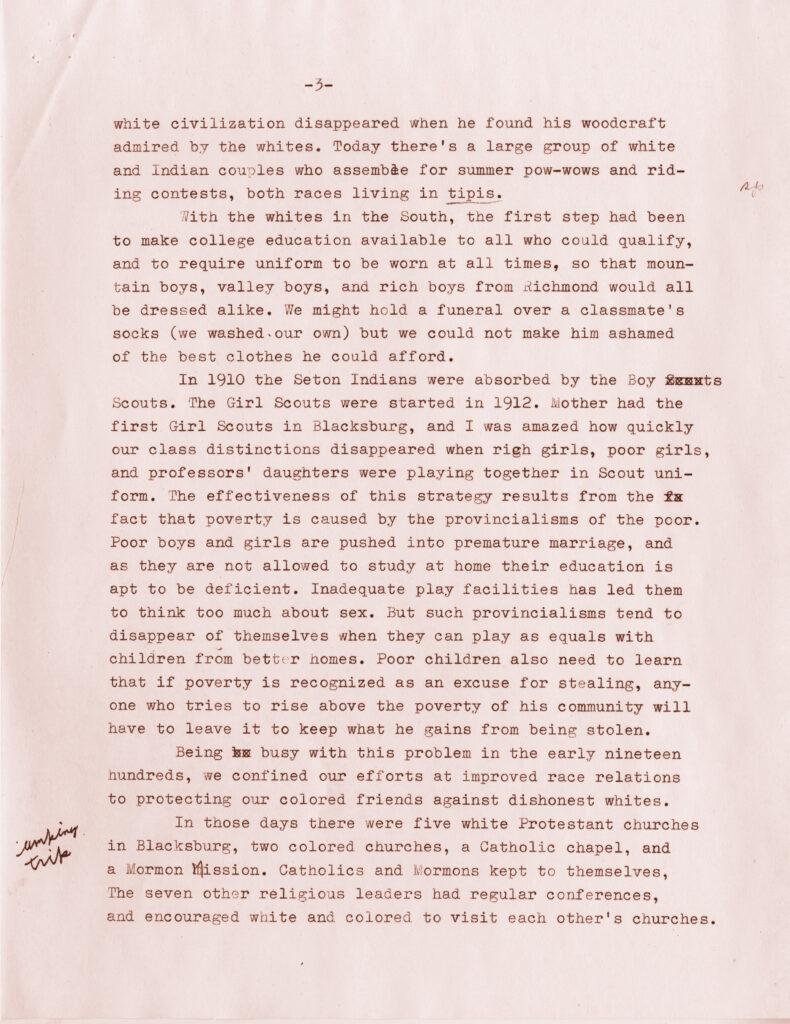

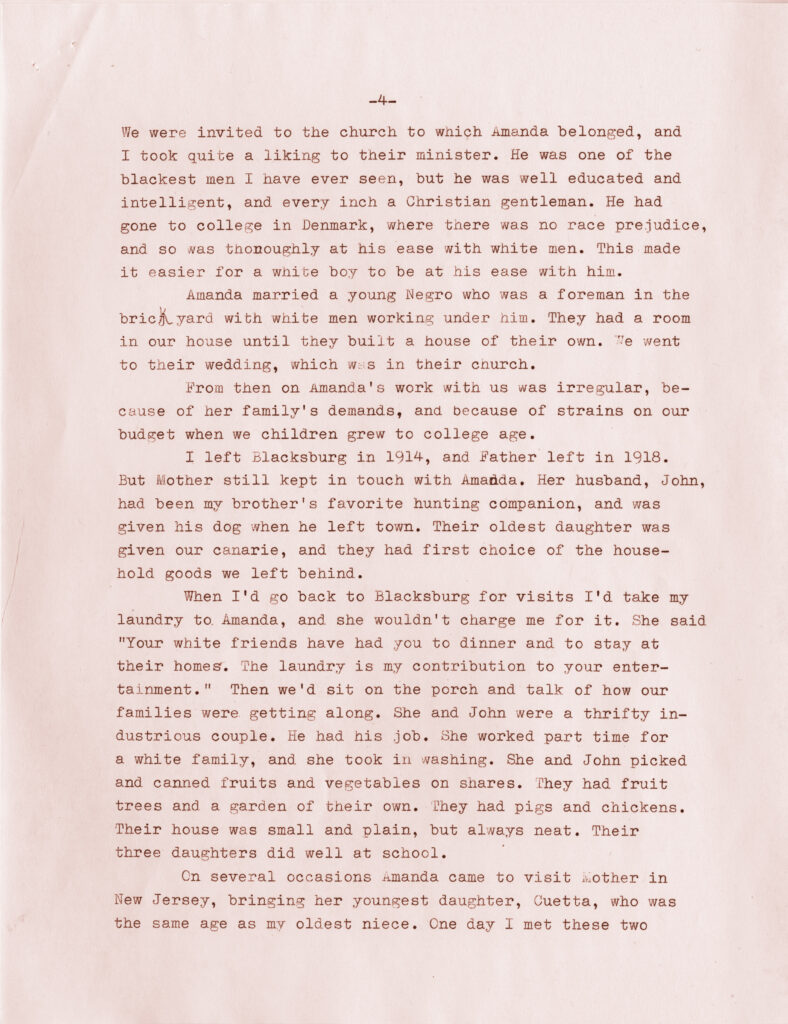

According to the Blacksburg Museum & Cultural Foundation, Tadmore Light Lodge had built or occupied a lodge hall in Blacksburg by 1907. The Odd Fellows Hall became a central part of New Town, an African American neighborhood in Blacksburg. The records from Tadmore Light Lodge show that the organization was active from the early 1900’s through the late 1960’s, holding regular meetings and social gatherings, collecting dues, and supporting members financially.

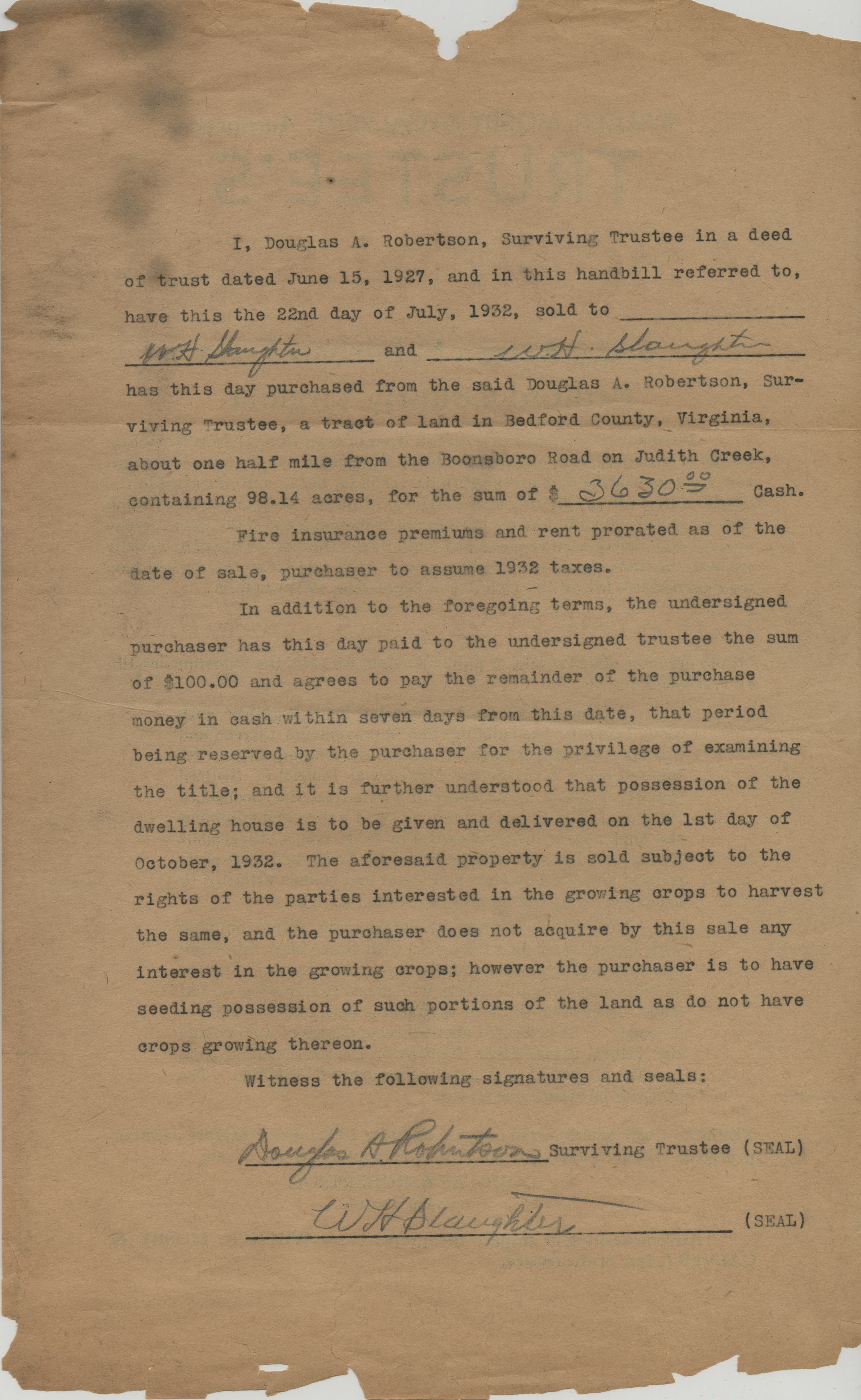

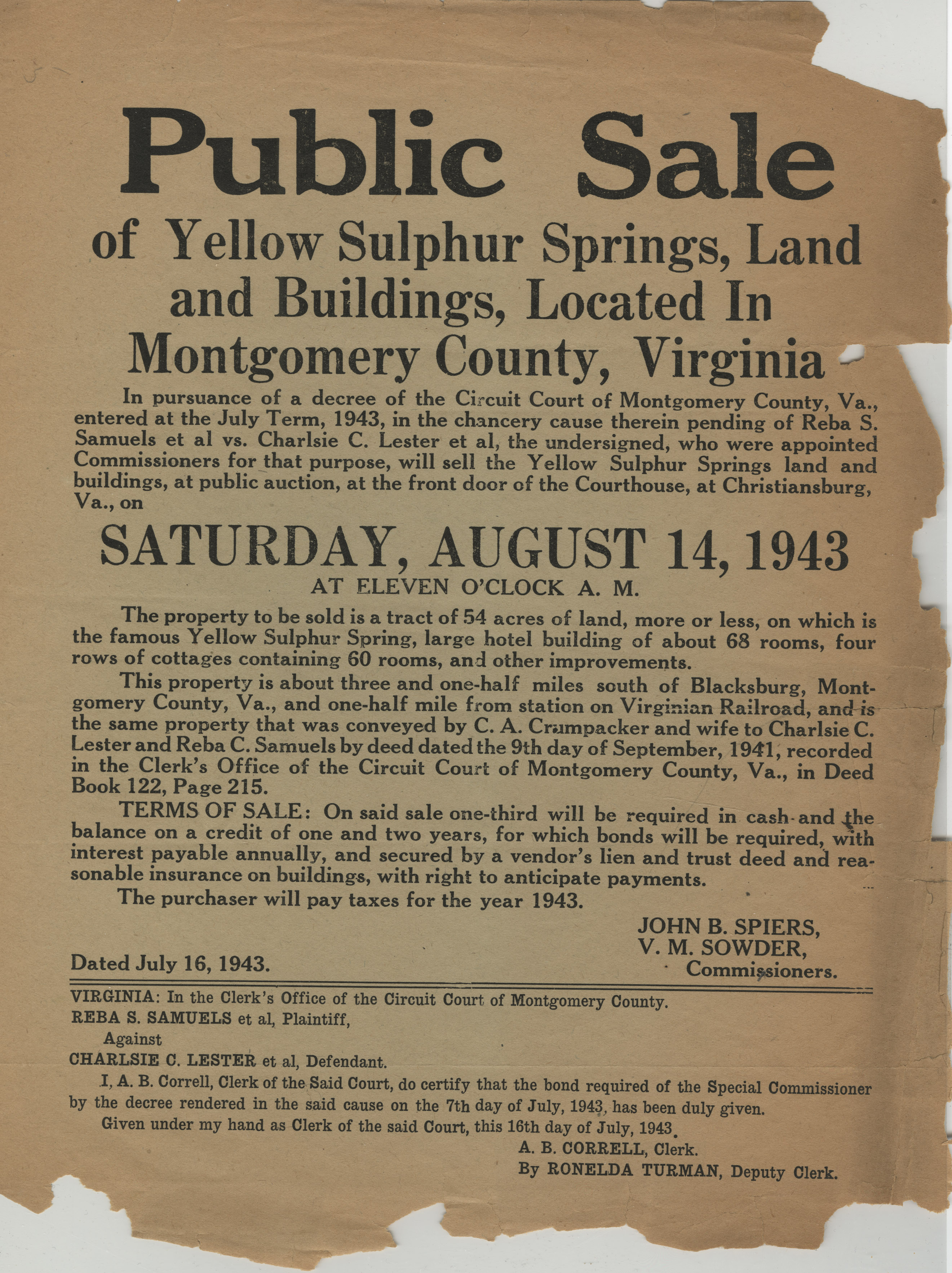

In the 1930’s, during the Great Depression, the GUOOF, like many other mutual support organizations, coordinated economic support efforts, insurance, and estate management for its members. The organization had regular reports from its Endowment Department about the amount of funds raised and who had been helped by those funds.

According tothe Interesting Facts noted on the GUOOF’s website:

In 1899, the GUOOF was the most powerful organization in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There were 19 lodges and over 1000 members in the city. The organization had $46,000 in property, including two lodge halls. The organization

also had its own newspaper, The Odd Fellows Journal.

Members of the lodge in Blacksburg connected to the larger fraternal society through district conferences and national publications, including The Odd Fellows Journal. By the mid-1940’s, the Blacksburg lodge was receiving another publication: The Quarterly Bulletin. The Quarterly Bulletin was published in Philadelphia and appears to possibly have replaced The Odd Fellows Journal.

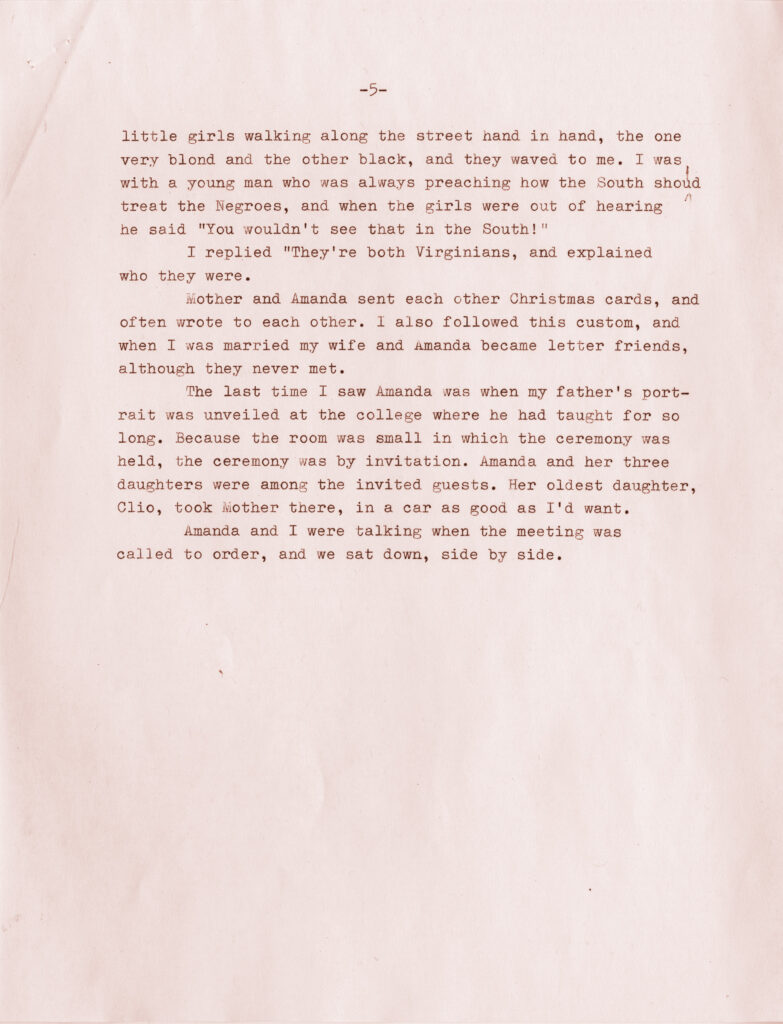

Of course, while the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows was an integral part of the community and helped to keep black Americans on their feet through the Great Depression and the Jim Crow era, it was also a secret fraternal society. As with any fraternity, it had its initiation ritual and required a firm commitment from its members. As early as 1929, the Applicant’s Agreement was worded like a legal contract – binding unless the law said it wasn’t (and even then only the part the law struck down became null and void).

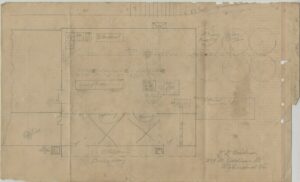

The ritual changed a few times over the years and we have at least 2different versions in our records (possibly 3). Joining the GUOOF involved anelaborate and solemn ceremony. Everything from the positions of people in the room to what was said was laid out in detailin the ritual book. I’ll give just a glance at the ritual, showing the initial setup and definition of some roles within the organization (the full book is much too long to share here – AND as a member of a fraternity myself, I would feel guilty sharing another organization’s secrets). Enjoy!

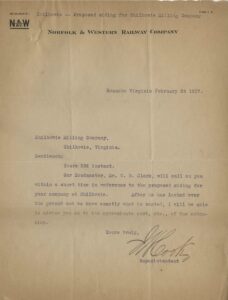

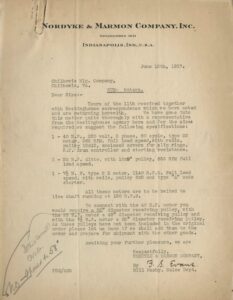

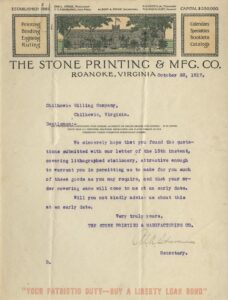

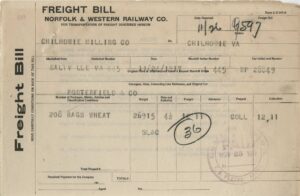

If you want to know more, stop by Special Collections and ask for theBlacksburg [Virginia] Odd Fellows Records, 1902-1969, Ms1988-009. The records include financial records, correspondence, minute books, brochures of several annual conferences, by-laws and odd issues of the Odd Fellows Journal for the men’s lodge. There arealso correspondence, minutes, and financial records for the women’s group – the Household of Ruth (check back next month for a blog post about the Household of Ruth in honor of Women’s History Month).