So you think archival work is boring and routine, that nothing could be so harmless and mundane as arranging papers and then writing summary descriptions of them? Maybe you think the most frightening thing an archivist encounters in a typical workday is a misfiled folder or a paper cut. Well, let me tell you: a misfiled folder can be a pretty ominous thing, and as for paper cuts, hey, those things can get infected. And if you were to delve deep into the dark, quiet recesses of Special Collections, you might be shocked to find archivists with hands stained crimson (with red rot), their clothing torn (by sharp, rusty paperclips), and their minds shattered by a blinding stench (from decaying film negatives).

If none of these prospects strike you as particularly sinister, then also consider this: Archivists often spend a great part of their workday hanging out with dead people (no, Im not referring to other archivists). In arranging the personal papers of long-deceased individuals, we often come to know them pretty well, not only the bare facts of their lives, but their habits, their successes and failures, and their oddities. Truth be told, dead people can be pretty creepy sometimes, and when it comes to creepy, the Victorians, preoccupied as they were with mortality and the macabre, take the cake. These are the people, after all, who popularized the gothic novel, sances, so-called freak shows, and post-mortem photography. Several of our collections from that time period contain another creepy artifact of Victorian culture: the dreaded lock of hair keepsake.

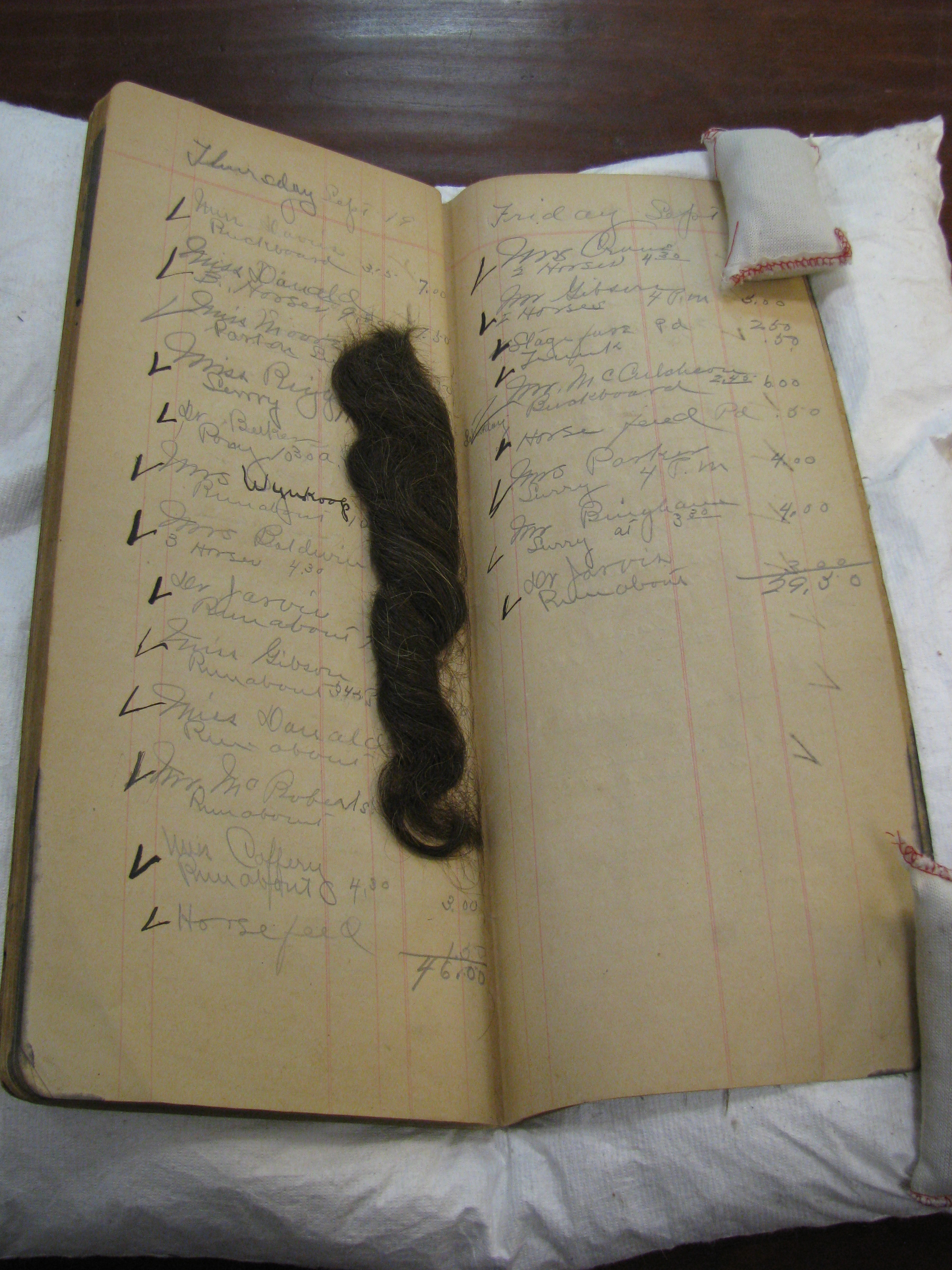

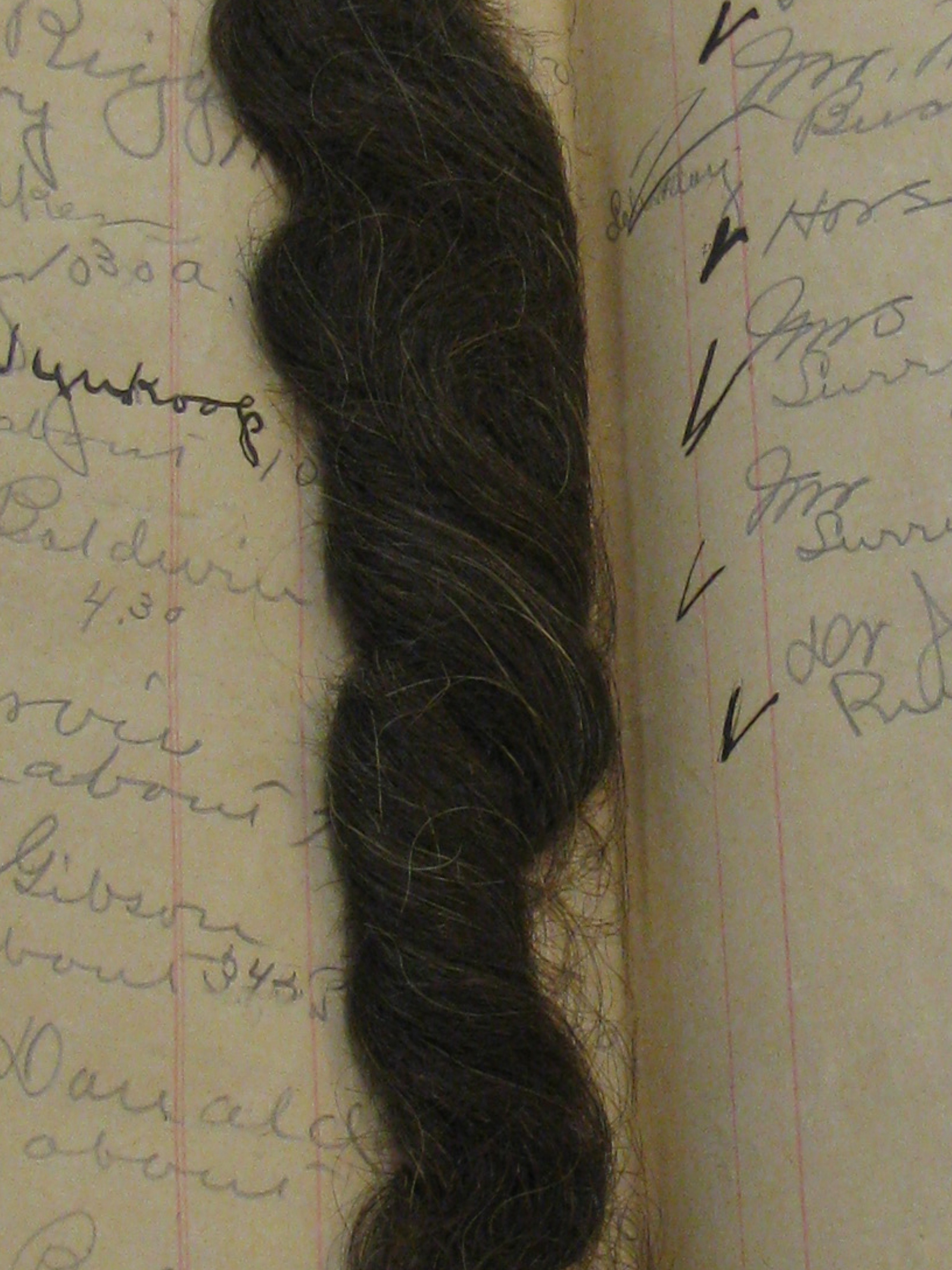

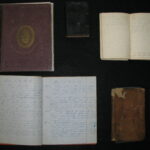

Now of course a lock of hair seems a fairly innocuous thing and wouldnt normally be associated with creepiness, but when youre thumbing through the century-old account ledgers of a long-defunct livery stable, the lastwell, perhaps near to the lastthing you expect is for a big clump of hair to pop out at you. Thats exactly the shock we recently got, however, when reviewing the Warm Springs, Virginia Ledgers (Ms2014-003), a collection purchased earlier this year.

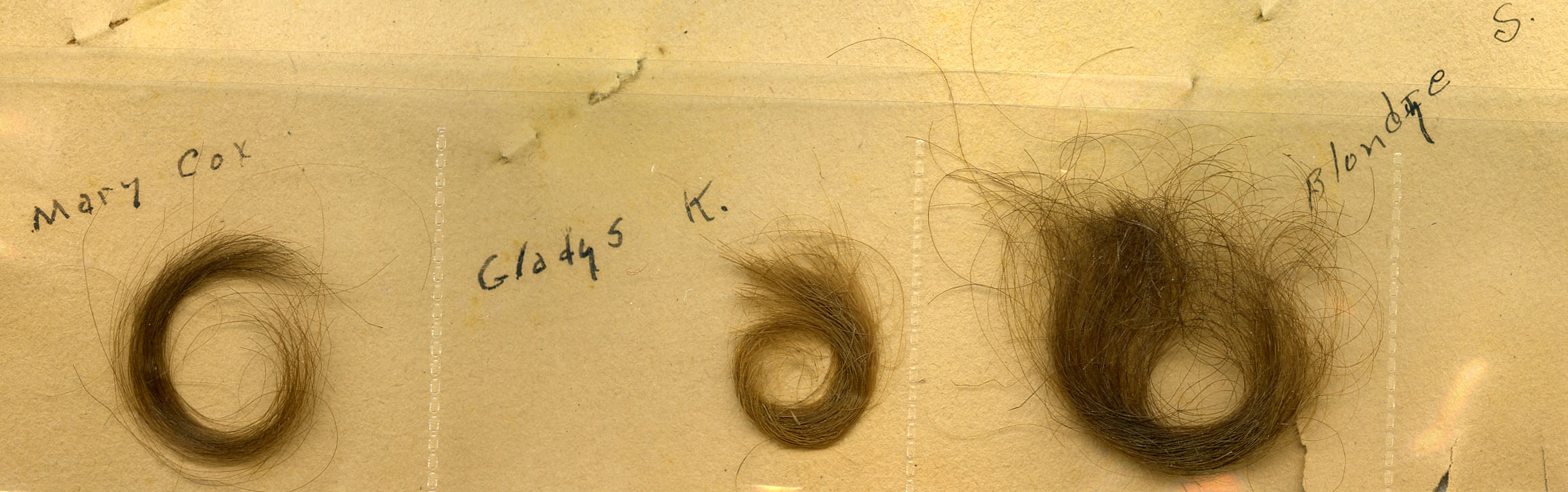

Though locks of hair continue to be clipped and kept as mementos, usually by parents who want a keepsake of their infant children, the sharing of a lock of hair between lovers as a symbol of devotion is a tradition that has largely fallen out of favor. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, however, it was a very common thing for a lover to request a lock of hair as a keepsake. Within the Frank C. Kitts Jr. Scrapbook (Ms2010-20), in fact, may be found small ringlets that Kitts, a native of Tazewell, Virginia, obtained from three different women, seemingly as a chronicle of his romantic conquests.

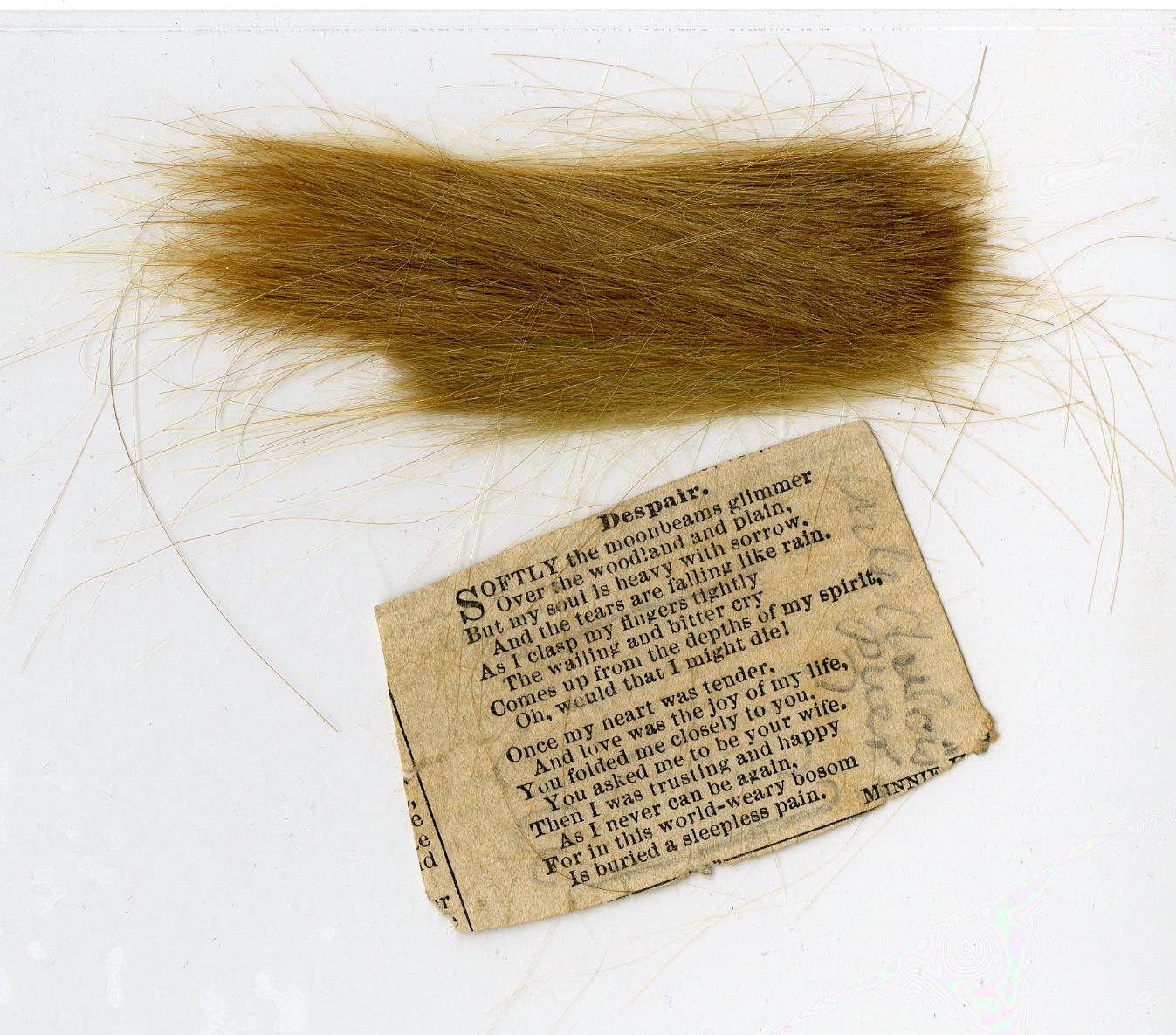

Locks of hair were also often kept as mementos of deceased loved ones. Such would seem to be the case with a small, loose bundle of reddish-blonde hair in the Vivian Coleman Bear Papers (Ms2009-086). The lock is accompanied by a poem titled “Despair,” clipped from a newspaper, which concludes, [I]n this world-weary bosom / is buried a sleepless pain.

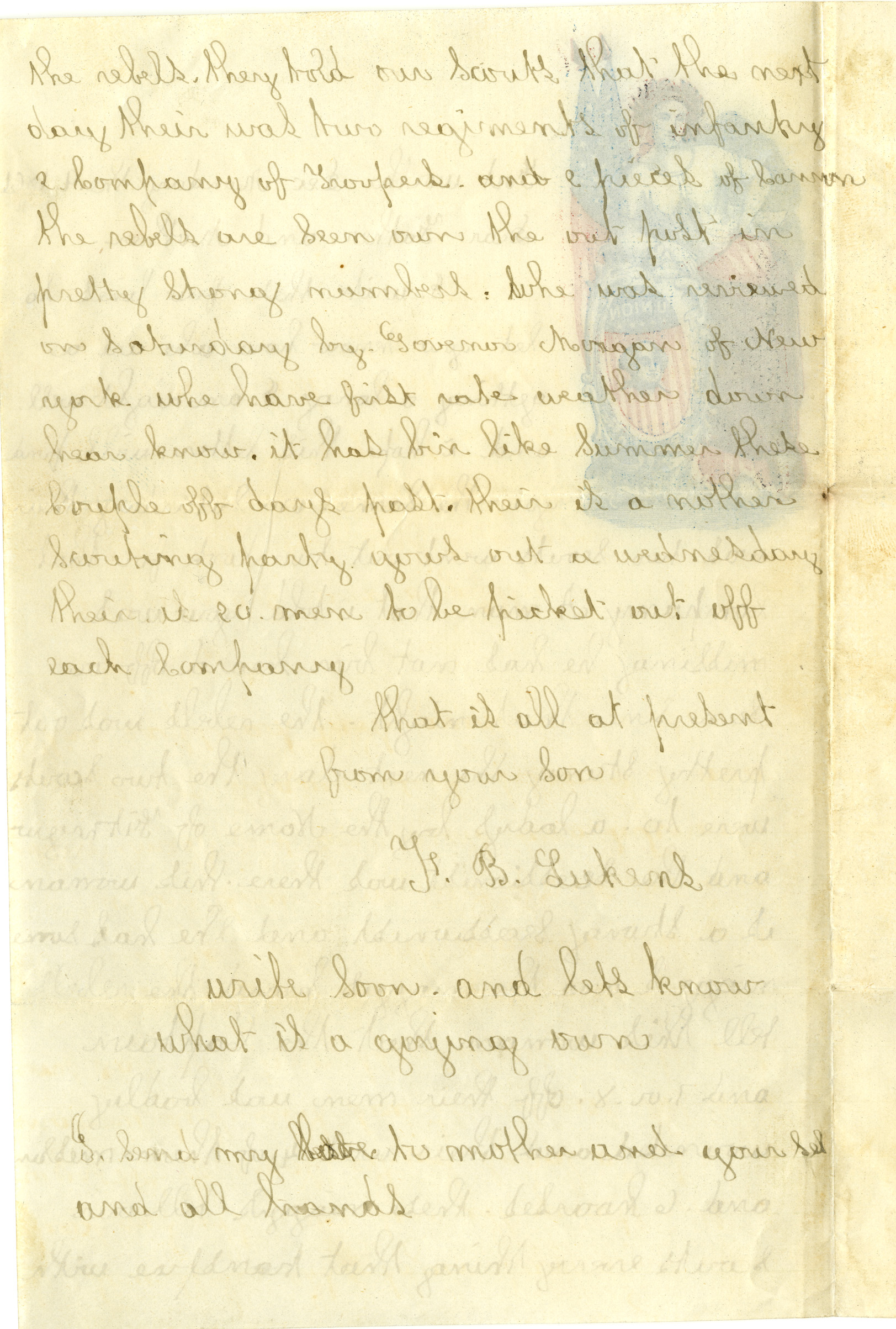

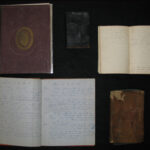

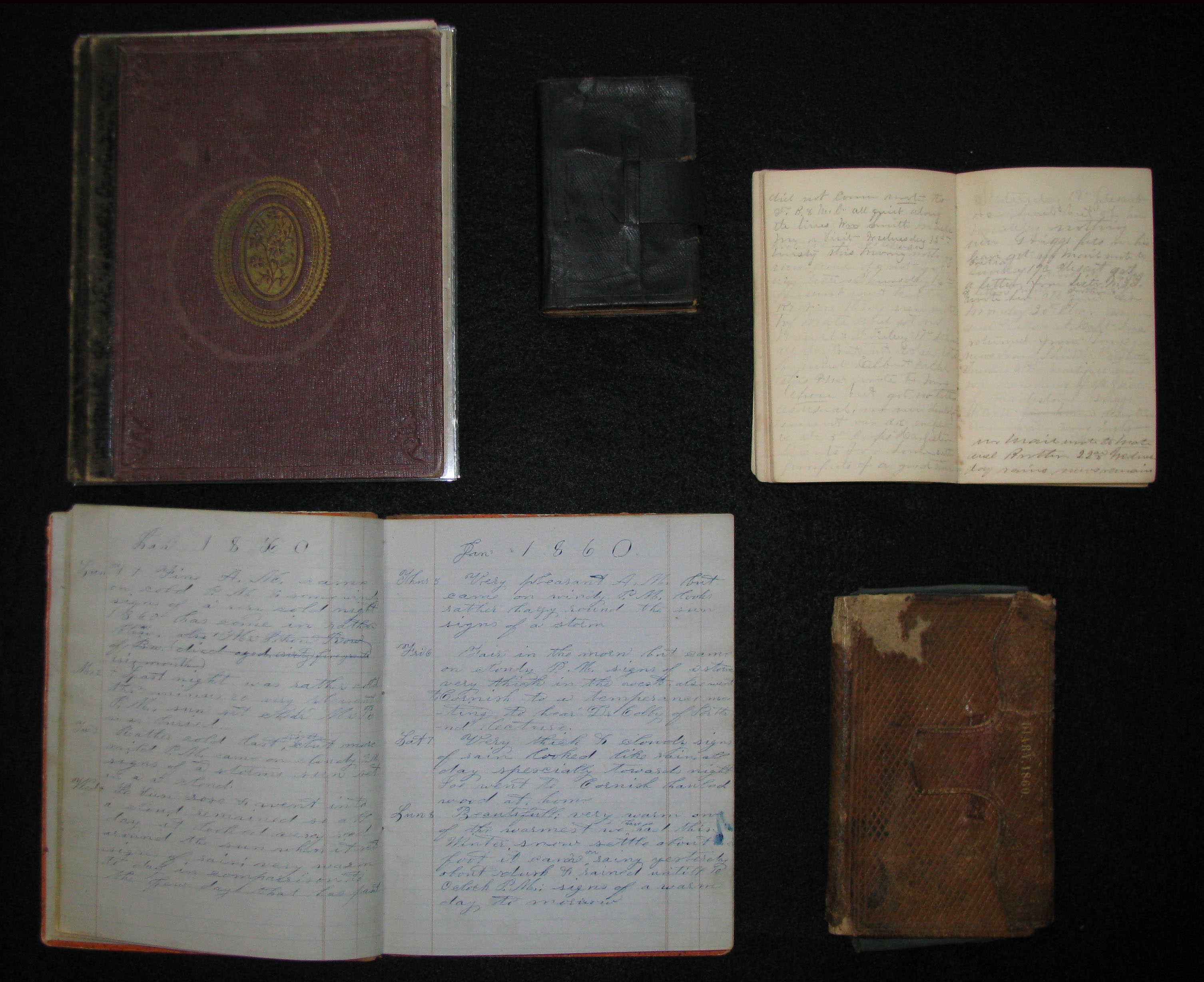

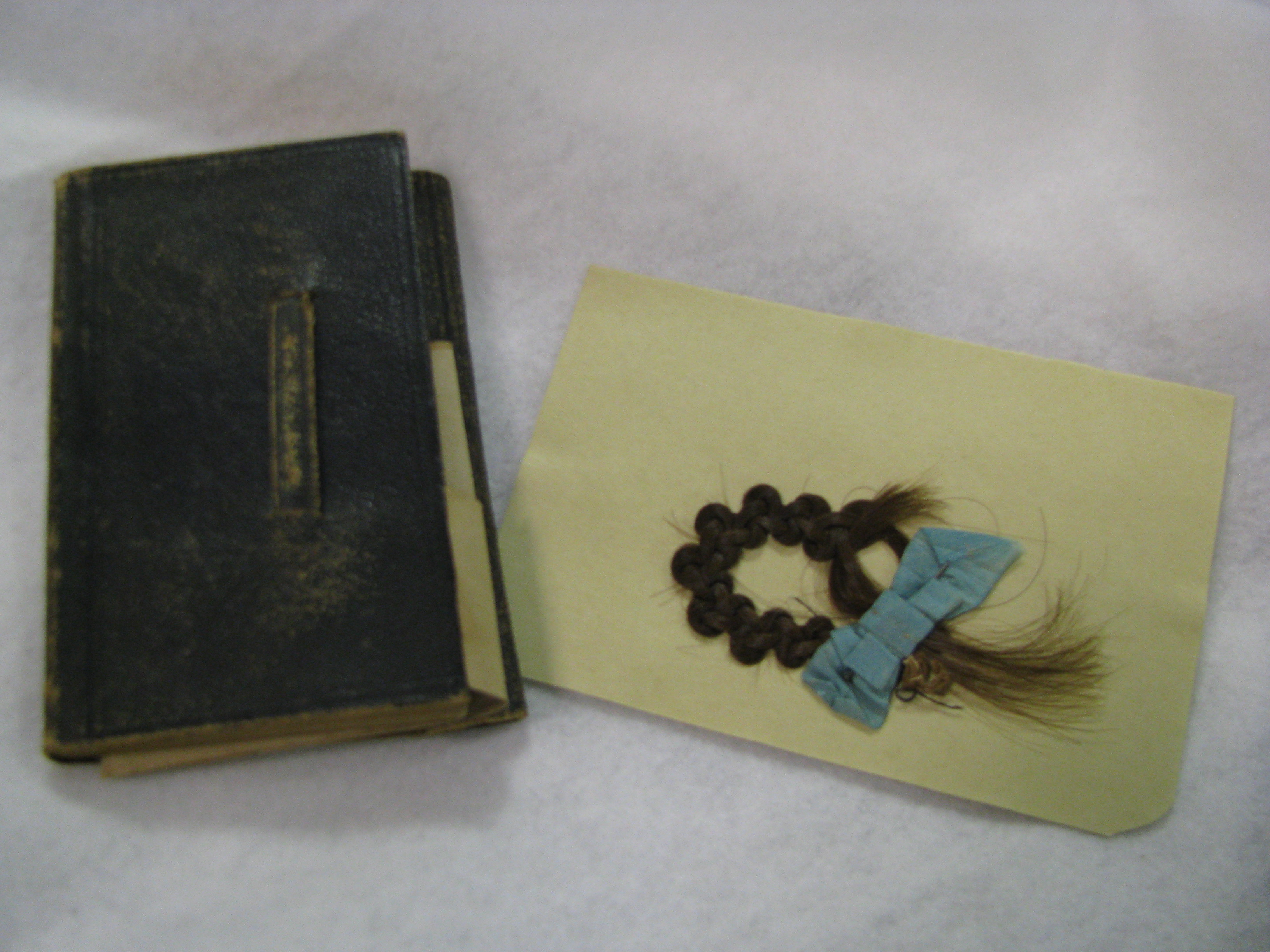

The symbolic associations and physical qualities of hair gave rise to its use as a medium for artistic expression during the 19th century, and hairwork became a fashionable handicraft, with jewelry, accessories, and wall ornaments being meticulously fashioned from human hair. Unfortunately (well, fortunately, as far as Im concerned), we have no examples of hairwork in our collections. Most of the locks in our collections are simple affairs, either kept loose or bound with a small ribbon. Within the back of a Civil War-era diary found in the John D. Wagg Papers (Ms1992-048), however, may be found a rather fancily braided ringlet.

Within our collections from the Victorian era are many other locks of hair. The owners of these tresses are sometimes identified, but more often theyre not. And so were left today to wonder just who they were, these dead people with their clipped hair, and to be terrifiedokay, not terrified, but at least vaguely and mildly repulsedby the little pieces of themselves that they left behind.