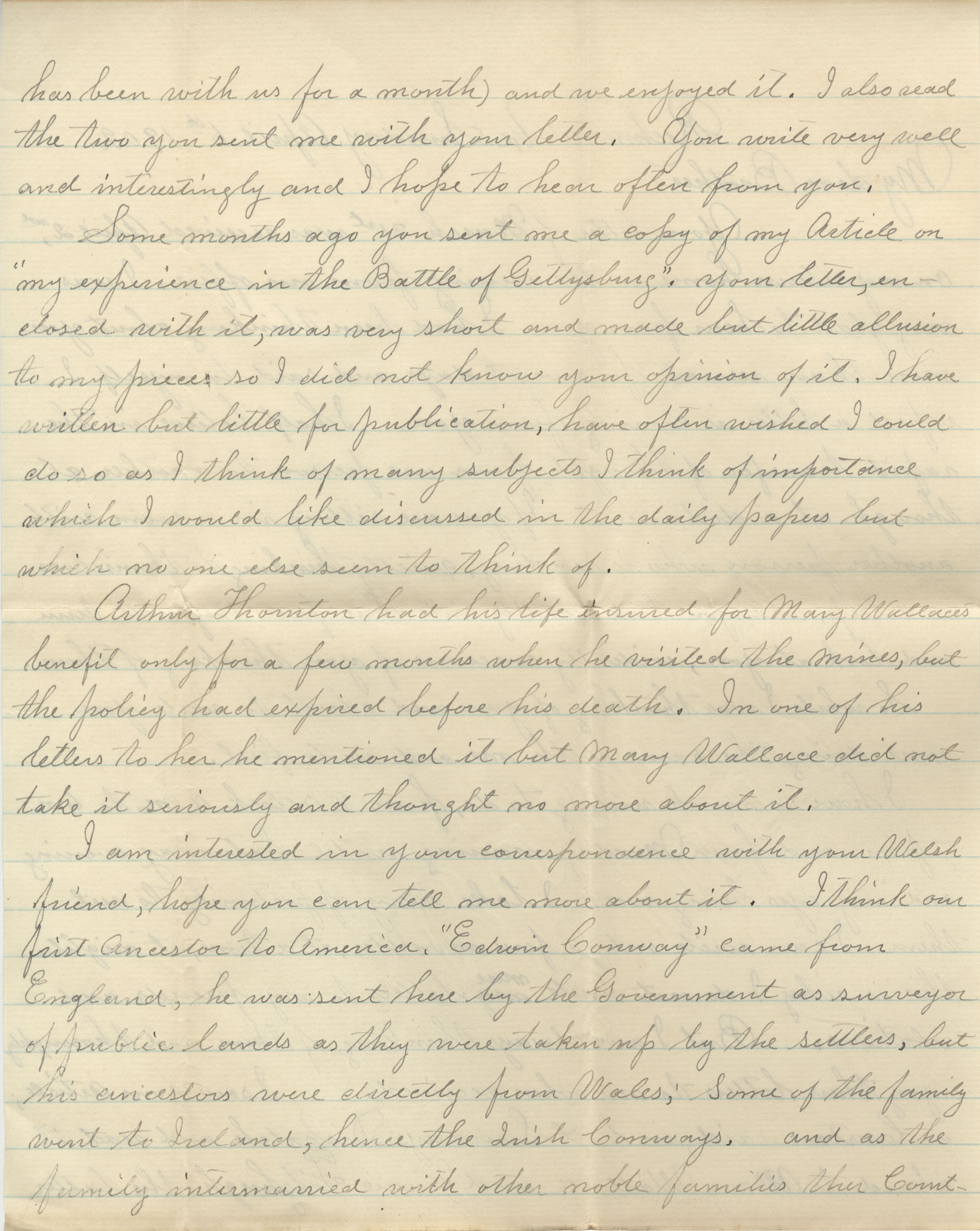

Over the course of three decades, an ex-Confederate soldier named Catlett Conway dutifully wrote a string of letters to his half-brother, Dr. William Buchanan Conway, or Willie, of Athens, Georgia. While some of the letters are addressed to Catlett from his daughter Mary Wallace or brother John, most of the letters begin with My Dear Brother, or Dear Willie, and always inquired after the health and happiness of all members of the family. William Conway, five years Catletts junior, served as the Physician and Surgeon for Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College the school we now all know as Virginia Tech in 1871 and moved to Athens twenty years later to run his own practice and contribute to medical journals. Catlett himself attended the University of Virginia in Charlottesville prior to the start of the war. Catlett often congratulated William on his published articles, which Catlett sought after and read with great interest.

Catletts own employment story followed a more scattered path over the years, as he held bookkeeping positions at the Richmond Granite Company and Richmond-based coal and tobacco companies. In his letters, he often recounted the events in a course of a typical day: what time he rose from bed in the morning, what time he ate breakfast and what he ate, how long he spent at his job and who visited him at his office, what time he ate dinner and what he are, and what time he went to bed. He was devoted to routines and considered any opportunities to read books and letters by the fireside in the evening to be his favorite time of every day. Throughout the letters, one can follow the development of gas and electric lighting, as Catlett often complained that his eyes were growing weaker as he got older, but advances in medicine and electric lighting helped him to continue his letter-writing up until the collection concludes in 1920, while he was in his eightieth year of age.

Catlett Conway was 52 years old when he was writing in 1892, meaning that he would have been among the many twenty-something-year-old men whose lives were changed forever by the Civil War and the considerably fewer who survived. Catlett refers to his Civil War experiences, as well as his attitudes toward Reconstruction, in many instances throughout his letters often in response to a new article or work of history that adds to Civil War literature. Catletts response to these pieces often fall into line with a sentiment of other ex-Confederates of the day who longed for the return of power to Old Dixie. Catletts memories of the war often lapse between wistfulness and pain, remembering the horrors of war among flashes of rosy prewar childhood memories. Occasions of dissatisfaction with new national directives for racial, political, social, and international policies are scattered among touching musings on heaven and the afterlife. Many of Catletts letters paint a unique, complicated picture of the Civil War and its legacy in public memory decades after its conclusion.

Finally, many of Catletts longer, more detailed letters have to do with the subject of travel and perceptions of his surroundings. Later in life, Catlett did a surprising amount of traveling especially by train to visit children, grandchildren, siblings, and cousins throughout the country. These letters give vivid accounts of train travel along mountain ranges (such as the Blue Ridge and Alleghenies), over rivers and gorges, and through rolling hills and fields in Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Ohio, and other states near and along the east coast. Catlett recalls everything from the meals given on the train to the bustle of the train platforms upon arrival and the details of family walks throughout cities such as Baltimore and Cincinnati. By the end of his life, Catlett had moved from boarding houses and the homes of his daughters to settle in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he often participated in Civil War-related events and reunions for veterans. Whichever city Catlett occupied, his letters always contained in-depth commentaries on that citys social, political, and economic situation as he perceived it.

Catlett Conway died in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in December of 1929 at nearly 90 years old. As Ive gotten to know Catlett in the later years of his life, Ive been able to keep track of his mental and spiritual growth, as well as his fluctuating health, until his death. Catletts prolific eloquence as evidenced by this collection holds a lot of potential for anyone interested in multiple interest areas, such as the Civil War, Reconstruction, the Gilded-to-Progressive Age; advances in technology, transportation, and medicine; the changing climates of race, gender, culture, the military, politics, foreign relations; everyday life in an American city the list goes on and on. From thoughtful personal insights and bold opinions and claims to musings on the state of the nation and the world, its as if Catlett Conway somehow knew that he had the potential to serve as an incredibly rich source of interest for purposes of research and just plain curiosity. You can find the entirety of the collection available online here.